Rare as it is, Emma Bruschi isn’t the typical millennial drawn to hype. And no, we’re not talking a miraculously gifted youngster on the cusp of defining fashion and power dressing through avant-garde notions of design. We’re talking about looking good while doing good. With a contemporary, bracing approach Bruschi is part of the new generation of designers advocating for a hyper-conscious style in craftsmanship. “What attracts me the most is to make my own materials, whether by fermentation, for instance, with Kombucha leather or the straw that I gather from French craftsmen,” Bruschi says. “On the process, I find my inspirations but most considerably, I find that a sheer emotion flows through the garment when I take the time to shape the material. It’s also a delight to know where these raw materials derive from and to meet people who are so passionate.” The newly-gained twist is visible in her MA’s pared-back, refreshing vocabulary. Guilt-free hybrids frame a narrative that stands on its own terms, reclaiming upcycled materials where possible as well as locally sourced artisanal fabrics. Think billowing volumes, breezy structures, and nature-friendly textiles. And trust us, this isn’t a prank. Just a jar of all-round great stuff worth the taking.

During this time of socio-economic uncertainty, to commemorate World Earth Day’s 50th anniversary, her journey reminds us of the impact of being resilient and meaning of change – challenging archetypes and fighting for the future of fashion. A brightly outspoken, ardent newcomer whose brew is (really) worth stirring. As such, we grabbed five with the designer and navigated the seamless dreamscape of natural fibers, reflected on the reasons why she rejects mainstream fashion and laying foundations for a bright future ahead. Shattering the conventional etiquette of modern artisanship, no doubt she’s one to watch.

Before we get right deeply into this, I want to make sure we cover the basics. Could you introduce yourself to us?

Hi FY! I’m Emma Bruschi, a 24-year-old graduate from HEAD Geneve. I’m ever intrigued by textiles, crafts and farming development.

What’s your earliest memory of fashion?

When I was a child, my mother had a small clothing store in Marseille and I remember that I loved going there on a weekly basis, especially on Saturdays. I sat in the back in the space all day watching customers, and I used to accompany her to Paris to select the items necessary for the store. Moreover, I recall her letting me sell the jewelry that I crafted with friends. It’s really at this time I think I wanted to make fashion my job.

Is culture important to your designs?

Undeniably. I’d say particularly my family background and my cultural heritage are at the forefront of my practice. This is what inspires me for all my creations, hence my will to portray my work in such key. I look for the past and old traditions, some stories that I’m acquainted with and others that require more research. This is often how I start my creative process, by reading a lot, collecting images and exploring techniques. In contrast, contemporary images cross-less my work over.

How has your MA collection evolved?

Well, in the beginning, I had a lot of trouble making silhouettes that I liked. I was trying to make complex volumes, but I couldn’t do it. It was really when I discovered the craft of straw that triggered me, that I found this material so fascinating to a point where I began to make more sober cuts to really highlight the plethora of materials I had developed since the beginning of the year. Thus said, most of the silhouettes got right the end of the year because I’ve repeated the looks of the collection several times.

What inspired you to probe into ethical fashion?

In all honesty, it was quite late when I realized that I was crafting eco-conscious fashion. For me, was never really a constraint or a goal; it’s just what I like to do and it’s part of my aesthetic. Nature and crafts have always been present in my life because I come from a farming heritage, so I was inspired to make clothes taking cues from those attributes. I always find it quite tricky to talk about ethical fashion, it’s a big word and most brands don’t have total control over their clothes, especially with the marketing acumen taking over. Essentially, even on my own brand scale, I just have to buy thread in a shop, not knowing its provenance or source of origin. It’s always a tricky one.

Have you faced difficulties considering the current global ecological crises?

Not personally, because I was rather made aware by educating myself on ecology. It was by discovering how clothes were made that I discovered the impact that fashion could have and that in my modest way I could offer an alternative.

Are you reluctant to follow the “hype” of modern fast-fashion (and luxury) brands?

I never cared too much about the “hype”, as it doesn’t comply with what I do. I prefer to do things that suit ethical thinking and are re-usable in mass consumption. Rather, I am criticized that my work is not contemporary enough, but I have been told so much that it no longer affects me.

Who are your top three designers you look up to?

I truly prize Jeanne Vicerial’s approach with Clinique Vestimentaire, which combines theoretical and practical research in fashion. I am also seduced by the aesthetics of Loewe and Palomo Spain.

What’s the story behind your brand?

For the moment, as I have just finished my studies, I don’t have a physical branding to chat about. But then again, when I get started, I would like to continue to be surrounded by brilliant craftsmen and that my workplace mixes agriculture, science, biotechnology, regional know-how botany and beyond…

Bet you notice designers pledging to be sustainable in their collections. As an environmentally conscious creative, how do you feel about that? Please elaborate.

I find it pioneering that brands are starting to engage and open their eyes. Today, such an aspect has become almost a compulsory cornerstone to have a good image, so we feel that for some brands it is really forced. Sustainability is a word that all brands use while remaining very vague about their real actions. There is not really a label for it, so everyone prides themselves on being sustainable. In reality, there are so many steps from the plant to a piece of clothing in a store that brands cannot control. And then I think that it’s not only the way in which the clothing was made, it is also a whole logic of consumption which needs to be changed and which must also come from the consumer, to buy less but better. For example, brands like Zara or H&M can never be sustainable for me because of their size and crafts logic.

You mentioned that you produce your own fabrics to create garments. Could you take us through your approach of material-sourcing?

What attracts me the most is to make my own materials, whether by fermentation for example with Kombucha leather or the straw that I collect or buy from a French producer. There I find my inspirations but additionally, I find that an emotion passes through the garment when I take time and care to realize the material. It’s also a pleasure to know where these raw materials come from and to meet people who are also passionate.

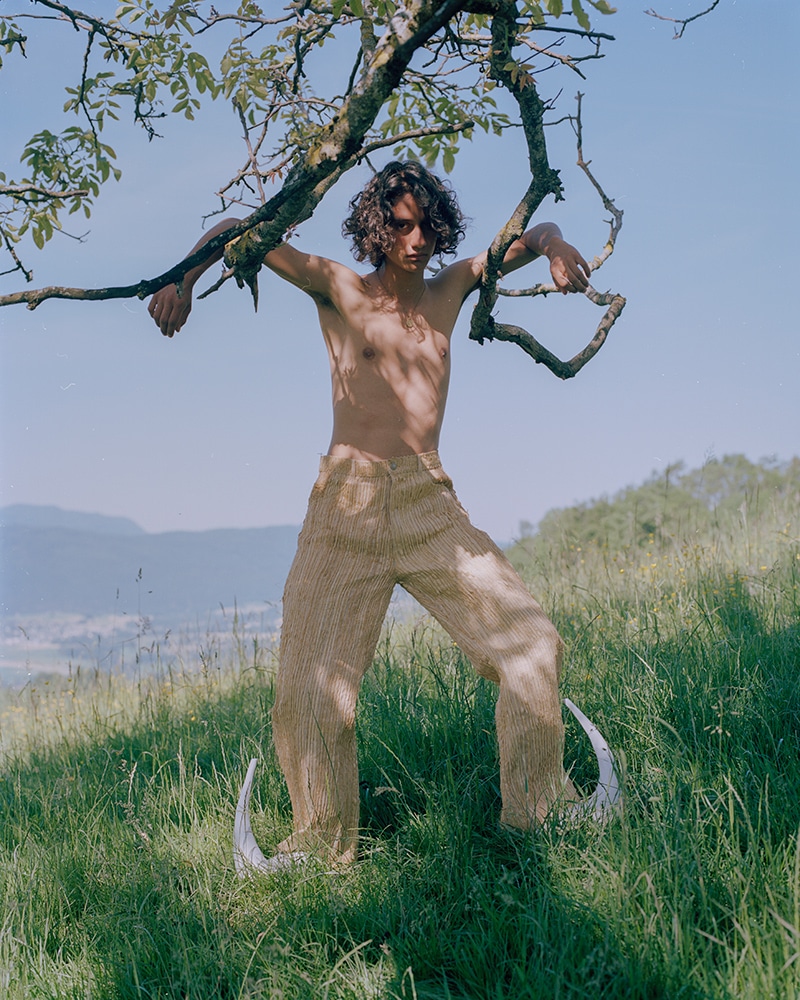

Describe the “Emma Bruschi” man.

I would say he’s nostalgic for a rural life that he’s unaware of, androgynous and ever poignant. He defines himself by his clothes and chooses them in accordance with his convictions and ideals. He is as sensitive to traditional crafts and techniques as the new natural materials that are emerging.

Can you describe the first garment you ever made?

The first memories of clothes that I made are, I believe, costumes for my little sister who loved dressing very much. For instance, I could make her a medieval dress in red velvet and linen or a Batman costume with the embroidered emblem. I knew a lot of techniques like knitting, sewing, embroidery but I didn’t necessarily make clothes before these costumes and I always embarked on projects far too complicated for what I knew, but every experience allowed me to learn.

What’s your signature piece? Your use of prints and fabrics is remarkable. How did such enthusiasm come about?

I think my signature would not be a particular piece but rather a material and with this collection, I would say that it’s straw. For all that is printed I loved to develop because it was with my boyfriend Jessy Razafimandimby who is an artist, we wanted to do something together for the collection, so he reinterpreted the canvas of Jouy compared to the Savoyard almanac. From there he made a lot of drawings that we worked on all over but also some drawings that we wanted to see larger, I was also able to embroider with straw some of the sketches. It was really cool to work together because it was the first time and I am glad that he is part of the collection because he was also one of my inspirations.

What are the key hindrances when trying to follow the sustainable route to feed your design practice?

It’s often hard to find quality raw materials, but all these little details that we do not necessarily think of (thread, buttons, lining) are often neglected. Sometimes, we rush on the first thing that we find because we lack time and that we have to make concessions. The biggest obstacle for me is having quality and trusted suppliers.

What other issues have you encountered along the line?

It was mainly problems with the experimental pieces like for example the kombucha leather which did not grow because of too low temperatures but also technically, everything that has patronage or molding I had a lot of trouble, so I got help. Often it was aesthetic problems the looks were changed many times and the styling too.

Is it hard being a new designer in a highly saturated age?

It’s pretty dizzying and sometimes it feels like our creations are going to be drowned in the middle of it. I prefer not to ask myself too many questions and move at my own rhythm quietly, and if some people like it then better.

Is this why this collection is more sustainable and less consumerist?

It’s rather common sense, as I find in a general way that there’s a rhythm that’s too fast in commercial fashion, for the copious number of collections and ever-changing novelty that is required to meet consumerist demands. This is not what I want to do in my work.

And then you were awarded the five-figure covetable accolade at HEAD Genève 2019. What thoughts went through your mind as soon as your name was declared? Were you expecting such?

No, I didn’t expect that at all, especially since my diploma jury didn’t necessarily go well. But for the show jury, I took a step back, changed some pieces and was more comfortable showing my work. It touched me a lot, especially when I could see the emotion and the joy that it had brought to my family and relatives who were in the audience. It was a very kind moment and I am very grateful to the jury.

Who would you like to see wearing your apparel?

Ideally, I’d like to not just appeal to a city crowd. In terms of the personalities and styles that I really like, I could cite Diane Keaton, Claire Barrow, Tilda Swinton, Joaquin Phoenix, Brit Marling, Avril Benard…

What’s next for you?

There are many projects in the pipeline! At the moment, I’m undertaking an internship for the magazine «Regain» which I adore. It’s a newspaper that celebrates the agricultural progress and the new peasant generation, looking at traditional clothes and folk festivals. I work there on both fashion and agricultural projects. Then we created CLUB POISSON collective with Aurore Marquis, Adeline Rappaz and Marvin M’Toumo, through which we will continue to make clothing accessories objects. Continue to develop our collectivist spirit and our creativity. I’ll also be giving workshops and courses to transmit the techniques that I’ve acquired through my path as a young designer.