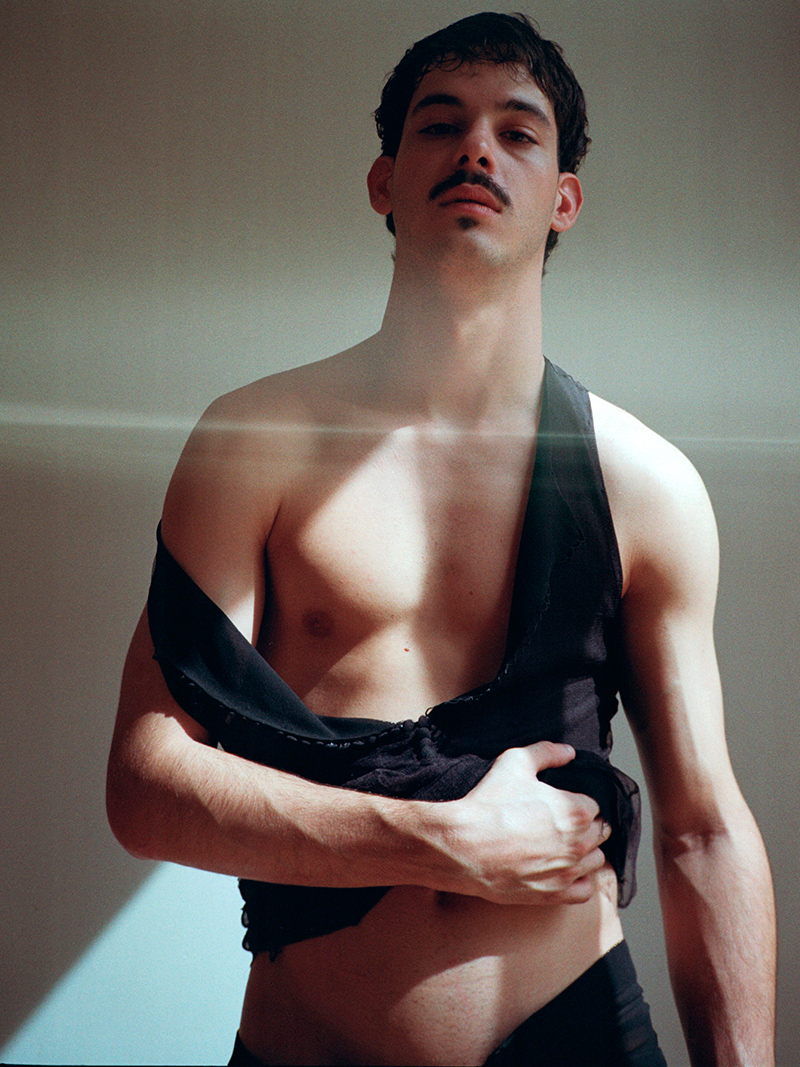

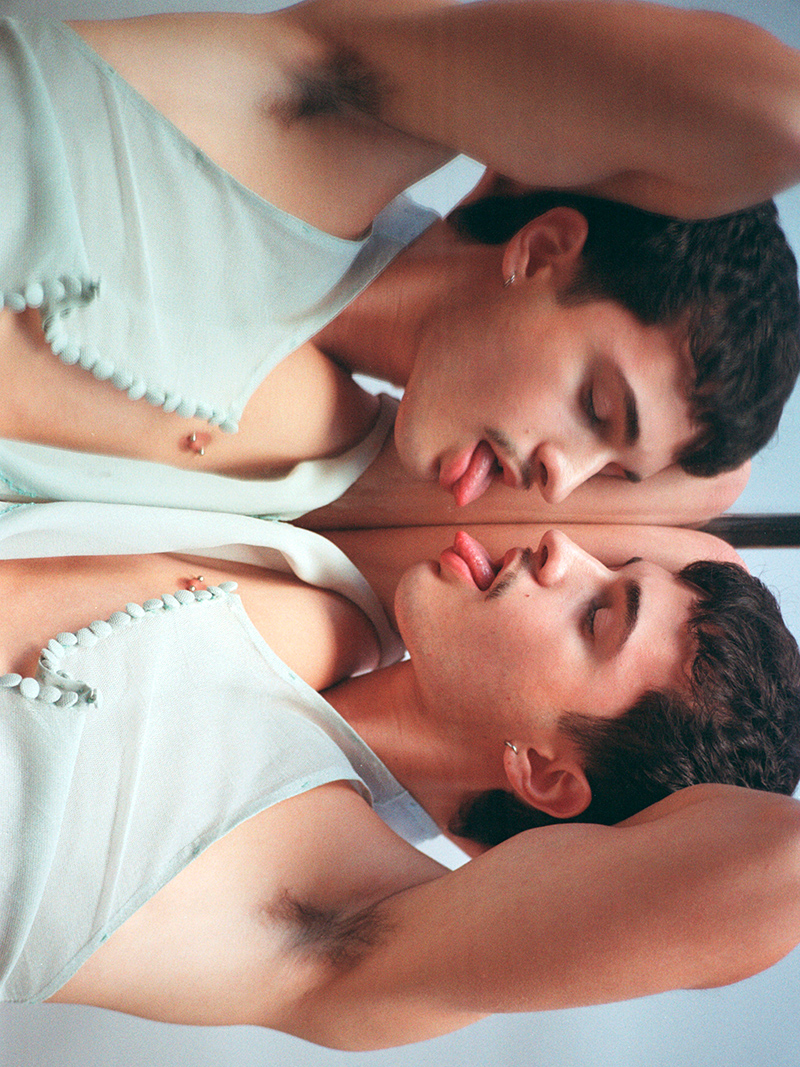

We Are Spastor’s latest project is not about nostalgia but about revisiting the foundations of their identity. The Madrid-based duo, whose collections first gained international recognition in Paris between 2005 and 2007, now return to those seminal years with a re-edition that feels both intimate and defiant. Each piece, constructed from silk georgette, tulle, and washed silk, reveals a devotion to process, the beauty of imperfection, and the quiet tension between fragility and structure.

Far from the speed and spectacle of contemporary fashion, We Are Spastor’s work exists in another rhythm: one that honours time, touch, and memory. The garments are sewn partly by machine but finished entirely by hand, exposing their interiors through layers of translucent fabric, as if revealing a private anatomy. Presented on plaster busts crafted by the designers themselves, the collection feels like a dialogue between body and sculpture, presence and absence.

Through desaturated tones, covered buttons, and hand-stitched loops, We Are Spastor evoke words like wound, halo, skin, pact, inheritance. This re-edition is not a return but a continuation. A way of tracing the spine of their work, reaffirming the delicate, enduring heartbeat of their universe.

This new presentation revisits pieces from 2005–2007, a period that established your international identity. Why did you decide to return to that specific moment in your history?

We made the decision because many people reminded us of those collections and garments, and it seemed like a good time to bring them back, to present them again and highlight them — also for ourselves. It coincided with Sergio having an accident and breaking a vertebra, and we realized that those garments had also formed our backbone within the collections. They were never pieces that disappeared, but ones that kept evolving throughout all our work.

What does “re-edition” mean to you — is it a literal reconstruction of past garments, or a reinterpretation through today’s perspective?

In our case, it depends on each piece. Some garments have been literally reissued, while others include small changes — in ease, rise, or fit — but always respecting the original essence. It’s about seeing how the garment coexists with the present.

How have your ideas and aesthetics evolved since those early Paris collections?

In the end, we’re still the same minds, but it’s 2025 now, and we like to think we’ve learned along the way — and that we’ll keep learning. Although, as from the beginning, there are contemporary things that don’t interest us… or they interest us only so we can translate them into our own language, or just as spectators.

Many of these pieces are made with silk georgette, tulle, and washed silk — delicate materials that require great precision. What attracts you to these fabrics?

We’ve always been drawn to fabrics that were supposedly meant for women — for their movement, their touch, their way of aging, and how they can be adapted and worn differently. We never understood why they weren’t present in men’s collections… as if fabrics had a gender!

You mention that every piece is finished by hand and that the sewing itself becomes part of the garment’s identity. What role does craftsmanship play in your creative process?

We’ve always loved that certain imperfection that exists within the perfection of hand stitching — the beauty of noticing that someone has worked behind it. That’s why we decided to use tulle to leave the interior visible, making it an intrinsic part of the garment’s identity.

The use of continuous covered buttons and handmade loops seems almost ritualistic. Is there a symbolic or emotional dimension behind that choice?

We like the repetition of buttons — the recurring, the numerical. Having to fasten hundreds of buttons creates a repetitive action that almost takes you into a trance… or the decision not to fasten them and let the garment fall naturally. Making that decision is part of it — it’s like seduction.

“Respecting the life of the fabric” is a beautiful expression. Could you explain what it means in practice?

In this case, it’s about not trying to restrain or reinforce the seams, letting the fabric fall naturally. The goal is to make the construction as pure and organic as possible, so that when you touch the garment, what you feel is the full expression of the fabric itself. Letting it age naturally. If you wear a silk tulle piece, you already know that by doing certain things you risk tearing it — but that’s part of the beauty. Don’t avoid it; embrace it.

The words associated with the collection — vintage, used, lived, intimate, skin, wound, pact, halo… — evoke a very tactile and emotional world. How do these ideas translate into the garments?

Through the structure of the garment, the treatments of the fabrics, the multiple seams, and the way the fabrics interact with certain parts of the body.

You describe a palette of desaturated colours and washed silks. How does colour (or its absence) shape the atmosphere of the collection?

In this case, the colours were determined by the originals — we wanted to respect that. In other editions, since we mostly work with deadstock fabrics, the materials themselves determine how we build the palette of the collection, but always within our imagination — as if a feeling or an action could lead you to a colour.

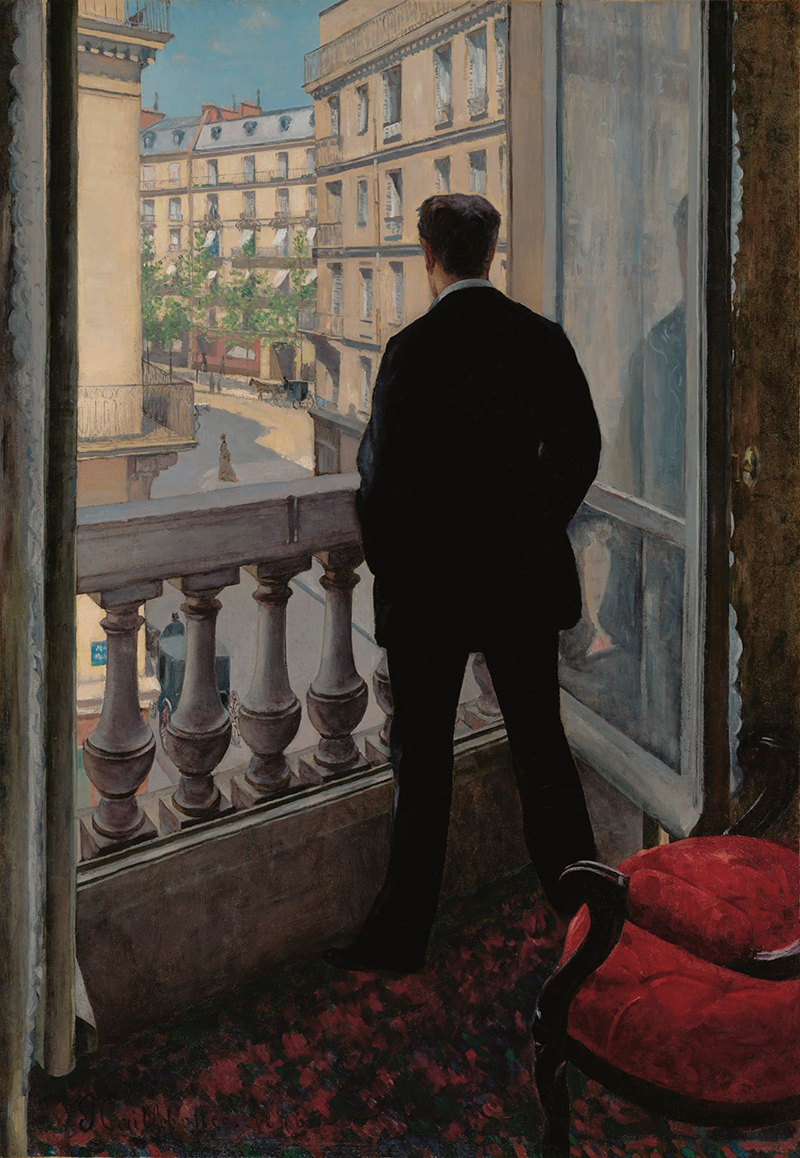

The pieces are presented on plaster busts made by you. What inspired that decision, and what relationship do you see between the human body and these sculptural forms?

For this presentation, we didn’t want to show the garments hanging one by one, or on real bodies. But it was necessary to see them worn — to have a base, a canvas — fragmented, marked by the scars of time. It’s a contrast between the classical form of sculpture and the contemporary language of clothing, an interaction between both.

Your work often feels suspended between fragility and structure. Is that contrast deliberate?

Absolutely — and deliberate. We love contrasts, confusion, being naked and dressed at the same time… underwear and a coat.

How does this re-edition dialogue with contemporary fashion, where speed and digital visibility dominate?

As always, and since our beginnings, it’s about finding our own place, our own rhythm. We don’t understand, nor do we want to understand, speed or ephemerality within our project.

We Are Spastor has always had a distinctive sense of time — garments that feel both past and present. How do you see your place in today’s fashion landscape?

A little Britney Spears.

What emotions or sensations do you hope viewers experience when encountering these reissued pieces?

That’s the part we love most about the end of the process. We don’t expect anything, but we love to see and hear how each person interprets it in their own way — how they make the garments theirs.

Finally, after revisiting your past, what do you imagine for the future of We Are Spastor?

We have projects we’d like to develop — collaborations, partnerships with the right people to bring them to life — things that make us vibrate, where we can share our vision.