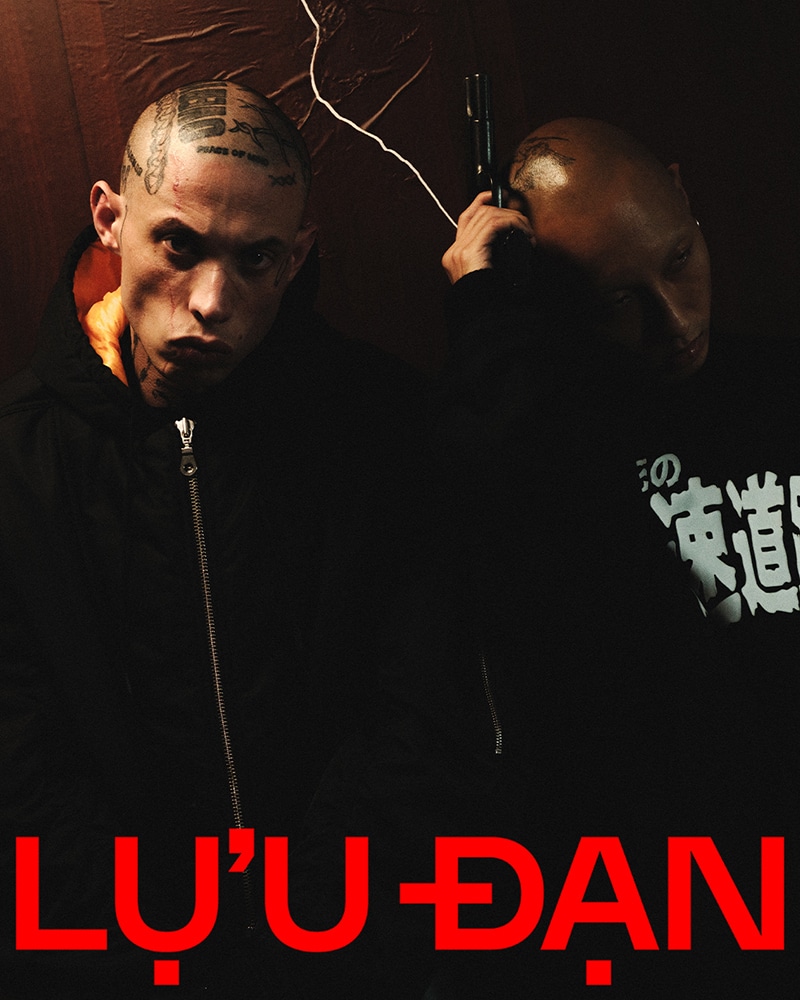

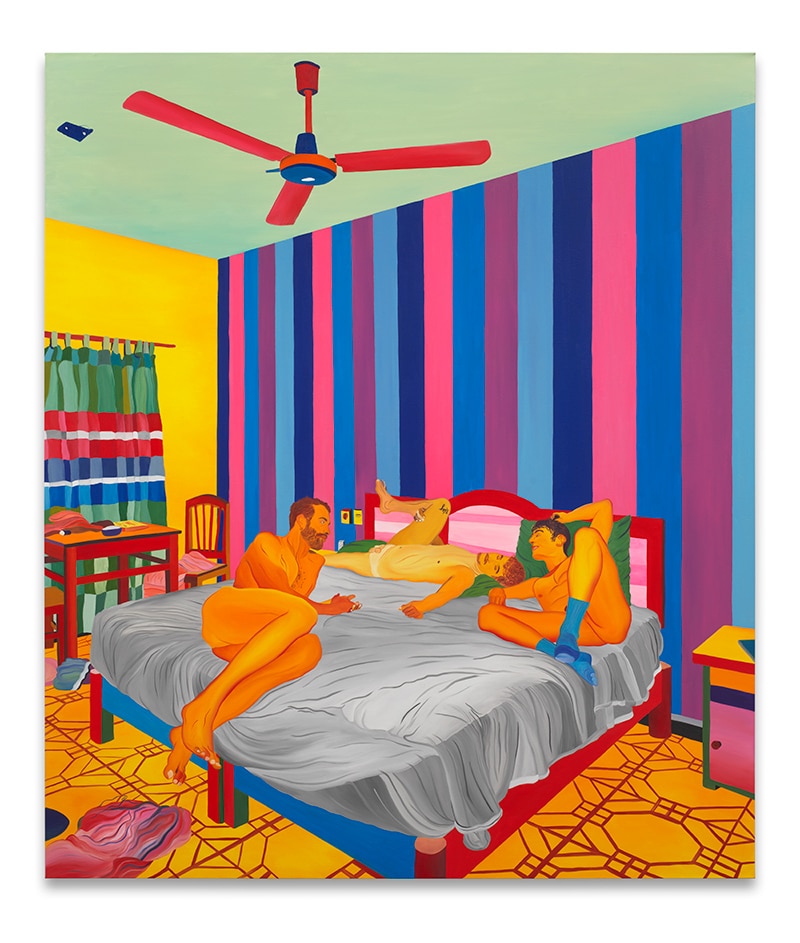

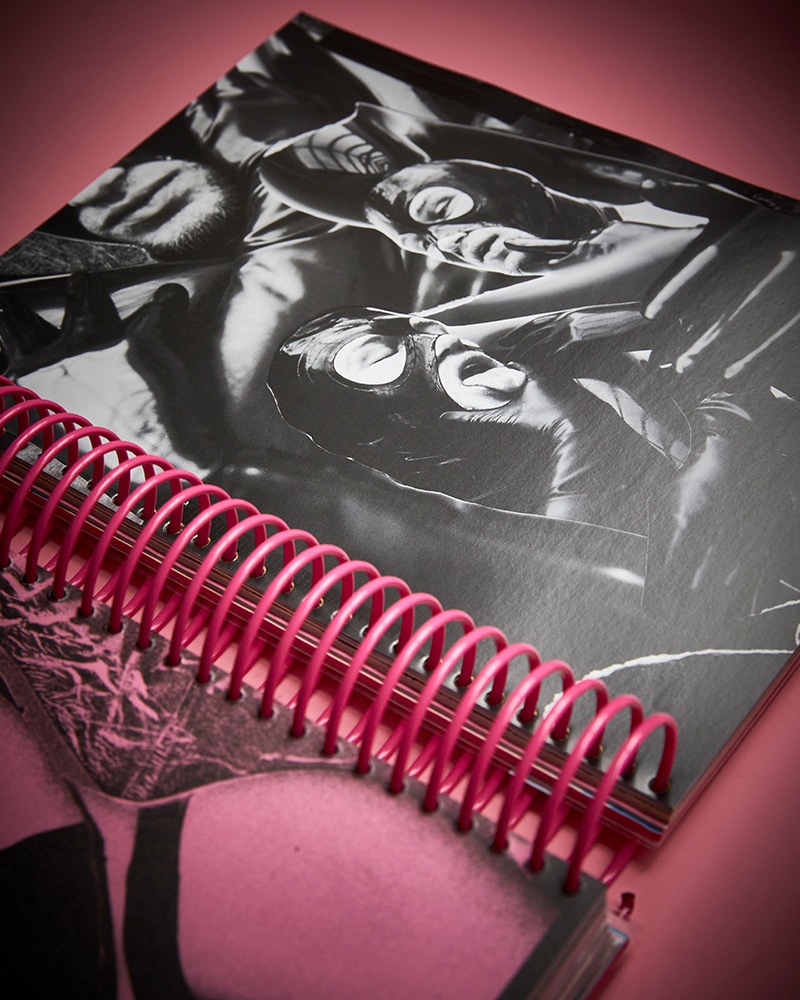

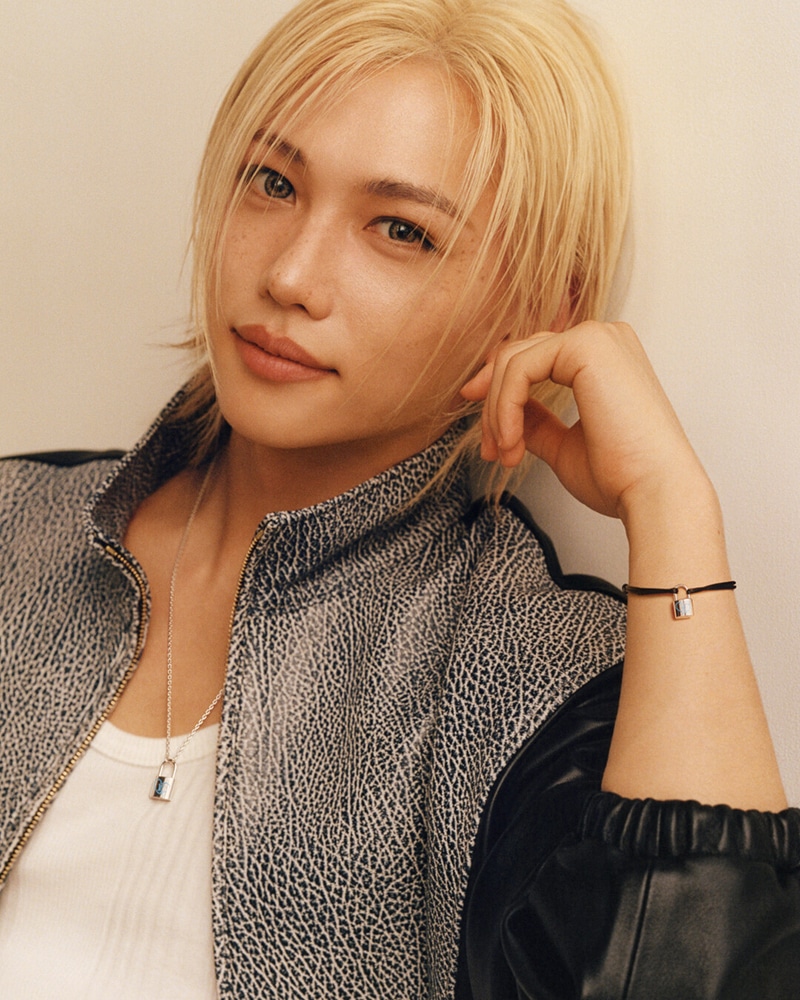

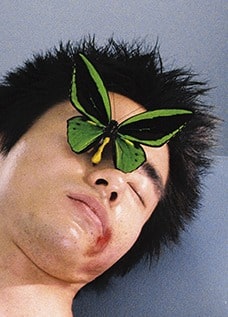

Gallery 1957 is proud to present Rituals of Becoming, a new exhibition by the Ghanaian-Togolese artist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi a.k.a. crazinisT artisT. Consisting of a theatrical installation that displays multichannel video projections, a readymade sculpture and a performance from the artist, the exhibition explores the assumed distinctions between gender identity, class, political injustice, violence and the objectification of humans. The immersive installation is composed of female clothes gathered and worn by the artist over the years, while the video installation depicts crazinisT artisT’s daily rituals of transformation. Collectively, these objects and videos question the strict categories of gender definition by urging us to rethink the fundamental construction of identity and gender performance.

Hi, Va-Bene, could you tell me more about yourself, what was your trigger to become an artist? Why the decision to work under crazinisT artisT pseudonym?

I was born to a Ghanaian mother and Togolese father whose mother was also from the south of Ghana. It is really a fragment of citizenship and identity because I owe my “Ghanaianess” to my grandmother (my father’s mother) by documents, not to my mother by ‘birth’. I trained as a professional teacher in Ghana and taught for four years and during my training and teaching, I was practicing as a pastor and evangelist. Though not formally ordained, I earned these titles in the towns and villages I worked in.

I had always wanted to study and become an artist since high school, but in fact, I did not even have the slightest idea what kind of art or artist. I did not know anything more of art than conventional painting and sculpture (even that there was a limitation), the artisanship and vocational skills until I entered the art school (Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology) where I studied Painting (BFA).The art world was distant, it seemed I was dreaming a [mirage]. These were the conditions for many Ghanaian students, which are still a problem, little is known about art unless you are fortunate to enter university. I am grateful for the kind of revolutionary teaching I encountered in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at KNUST. The university is really making an impact on the new generation of artists in Ghana. I think it is ‘catching flames’ and becoming contagious.

During my first years at the university, I realised that I was developing an extreme passion to art without form, content, and concept. I was only passionate to histories, presentations, and teachings. I started experimenting and exploring themes and materials and named myself crazinisT before I entered into performance art three years later. The name was just a pun, a ‘passion to’ … or ‘love for..’ a lack of a word to express myself to art. I never imagined any [coalition] between the name and my radical practice that emerged later, though many people now assume such intention. By the end of my final year in art school my works began to gain radical forms, approaches, and technics because of their tendencies to question identity, stereotypical labels of marginalised individuals and groups, gender politics and violations of human rights.

Your new exhibition Rituals of Becoming at Accra’s Gallery 1957 explores questions about gender identity, class, political injustice among other delicate issues, all themes that were exhaustingly explored by the art-world. What distinguishes Rituals of Becoming from the rest?

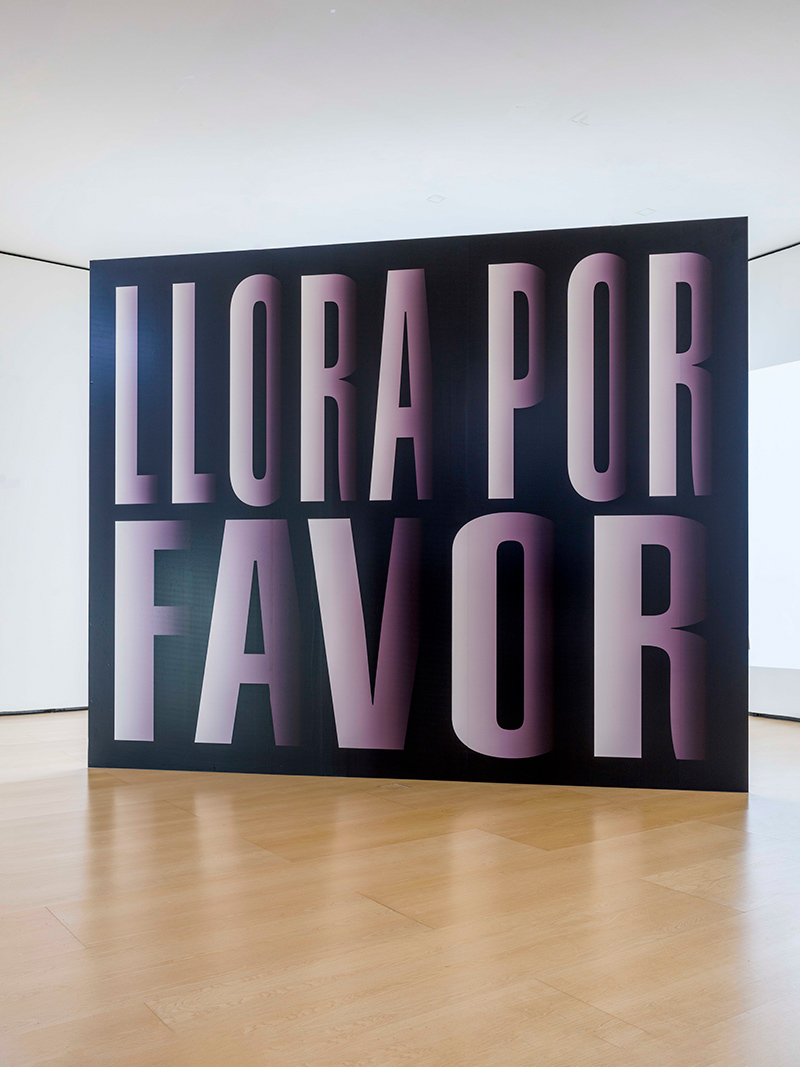

This exhibition reimagines and presents issues that have been seemingly exhausted and forgotten, but in context, as site-specific work and cultural specificity, it gives life to discussions of such subjects. Rituals of Becoming presents conditions of the process, product, intimacy, privacy and the body in sets of rituals that are embodied in the concept of ‘becoming’, that which is performed daily and intimately. The exhibition exposes the nature of voyeurism and exhibitionism in a parallel contestation, thus presenting the space as a violation and defying the conventions of the gallery.

Why do you think performance is the best medium to carry your message and vision?

In performance, I experience, you experience, and then we experience. There is exchange and sharing of roles, my audience and I perform and react to a set of situations. I think the body itself is very provocative when defiled or violated, thus evoking many questions and dialogues on its status. It has an intimate attraction since that is what we share in common as audience and performer, or the privilege and the marginalized.

I do admire your courage to assume your ‘’drag’’ persona in such a strict country as Ghana, how the local art community have been reacting? How is the current situation of LGBT communities?

For the local art community, I think I have lots of secret admirers, promoters, and supporters but they may not be bold enough to associate or declare their intensions, because of fear and political reasons. I have exhibited with groups and art spaces such as blaxTARLINES, Chale Wote Art Festival and Nubuke Foundation but some of them are very cautious of what I do with them.

As for the LGBT people, there are, though not as an organised community in Ghana. Most are just individuals who will have to navigate their own conditions despite their vulnerabilities. They live with stigma, prejudice, and insecurity. No one publicly declares his/her identity except ‘Trans’ where there is an obvious visual manifestation regardless of their sexuality. They are therefore exposed to more dangers than the others are. Their gender is largely misinterpreted because they become the ‘image’ for LGBT.

The established gender definition is constantly being questioned, becoming more and more obsolete, how would you describe this nu-gender, new identity, we’re trying to forge?

Well! Until it becomes nameless, its questioning will never end. I do not think we can even define it now, it will get more complicated with time, let’s leave it fluid.

All images courtesy of the artist and Gallery 1957 in Accra.