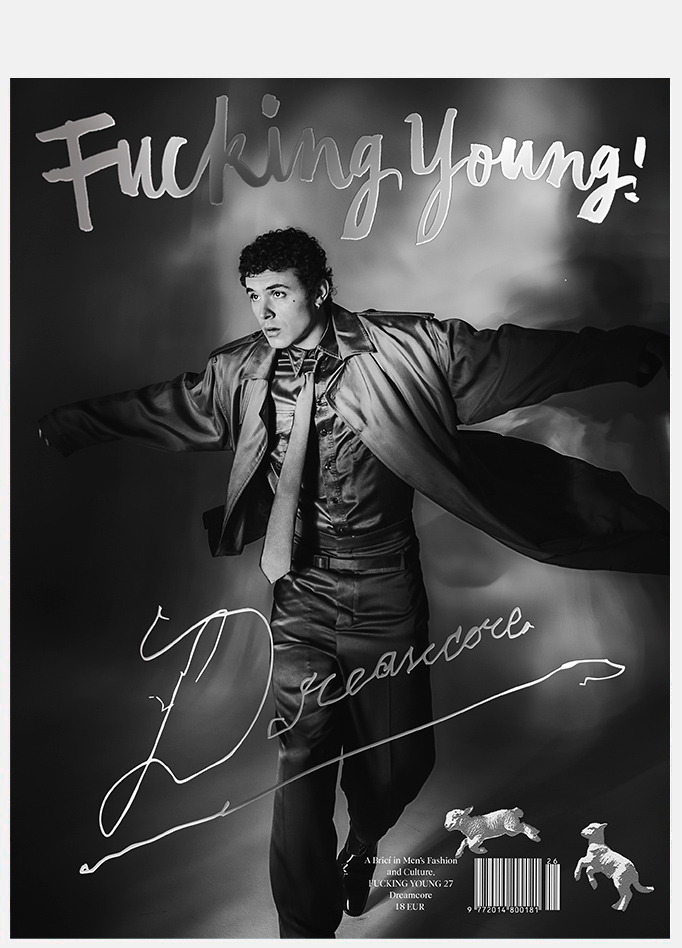

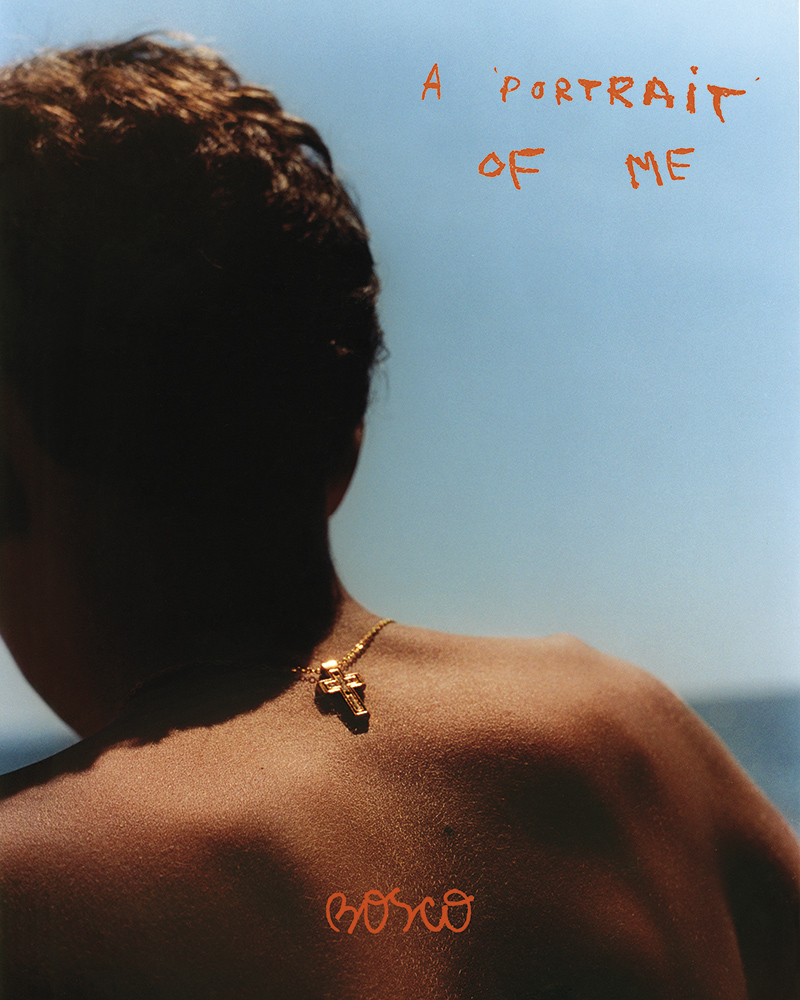

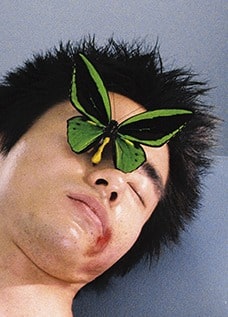

At a time when happiness feels postponed rather than promised, Macías steps into the noise with vulnerability as his weapon. The Spanish artist releases his debut album, Aún es pronto para ser feliz (It’s Still Too Early to Be Happy), a deeply personal record that blurs the lines between electronic music, lo-fi intimacy, digital distortion and emotional rawness.

Born from a need to be honest — with himself and with the world — the album captures the quiet chaos of a generation navigating overstimulation, heartbreak and self-reflection. Macías builds his universe from contrasts: processed vocals collide with solitary guitar takes recorded in his bedroom; nostalgic melodies sit next to fractured production and moments of light flicker through emotional collapse.

Across 13 tracks, the record traces the slow unraveling of a relationship, moving from calm acceptance to darker, more broken emotional landscapes without losing its sense of tenderness. References span genres and eras — from the textured guitars of Deftones and the visceral lyricism of Robe (Extremoduro), to the shadowy production of Salem and the experimental intimacy of Bon Iver, Dijon and Mk.gee — all filtered through a contemporary lens shaped by digital aesthetics and emotional honesty.

Aún es pronto para ser feliz isn’t looking for answers. It sits in the discomfort, embracing the idea that maybe, right now, not being okay is part of the process.

Your record was born out of the need to be honest with yourself. What was the first uncomfortable truth you accepted while composing it?

There wasn’t really anything I “accepted” while writing. Almost every time I write, I already have an idea of what I want to write about. I consider myself a very introspective and analytical person, and I always try to understand what I carry inside and why.

On the album, intimate guitars coexist with broken digital textures. At what point did you realize that this sonic clash was also a reflection of your own inner world?

To me, they go hand in hand. It’s true that playing an instrument has an emotion that something digital doesn’t, but the organic and the broken have nuances and textures that a guitar can’t achieve.

“Una sola hoja en movimiento” opens the album in a calm state. What was the last thing that made you feel calm in real life?

The countryside and a hug from my mother.

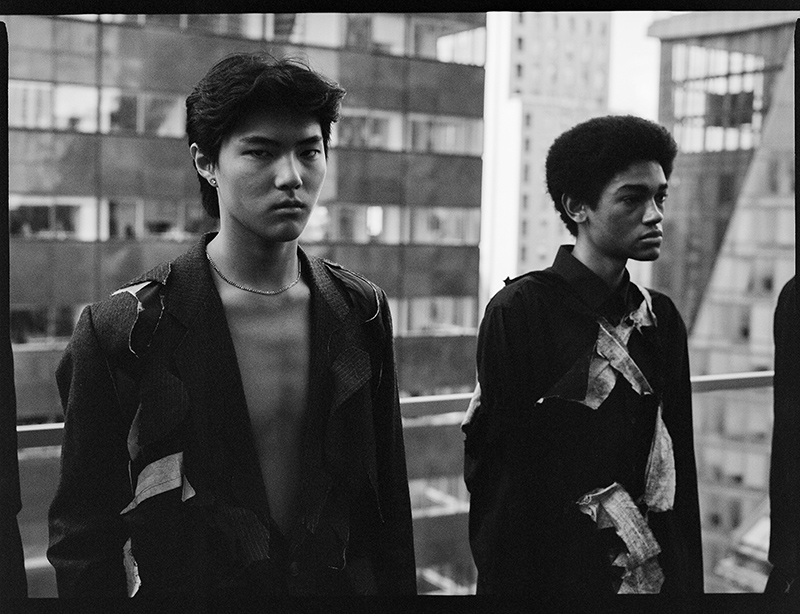

You say that for our generation “it’s still too early to be happy.” What is the most absurd pressure you feel has been imposed on us?

Identity. I’ve never understood that need to cut us all from the same mold. It’s something that always suffocated me a bit until I turned 18, and then I said, that’s it.

Your music moves between nostalgia and rupture. What is the smallest —almost insignificant— memory that still pierces you?

The memory of touch, or remembering a voice you can no longer hear.

Speaking of breakups: What plays in your head when something ends: noise, silence, or a mix of both?

I see them as a relay — they alternate and look for each other. I handle it much worse when my head fills with noise that I can’t stop.

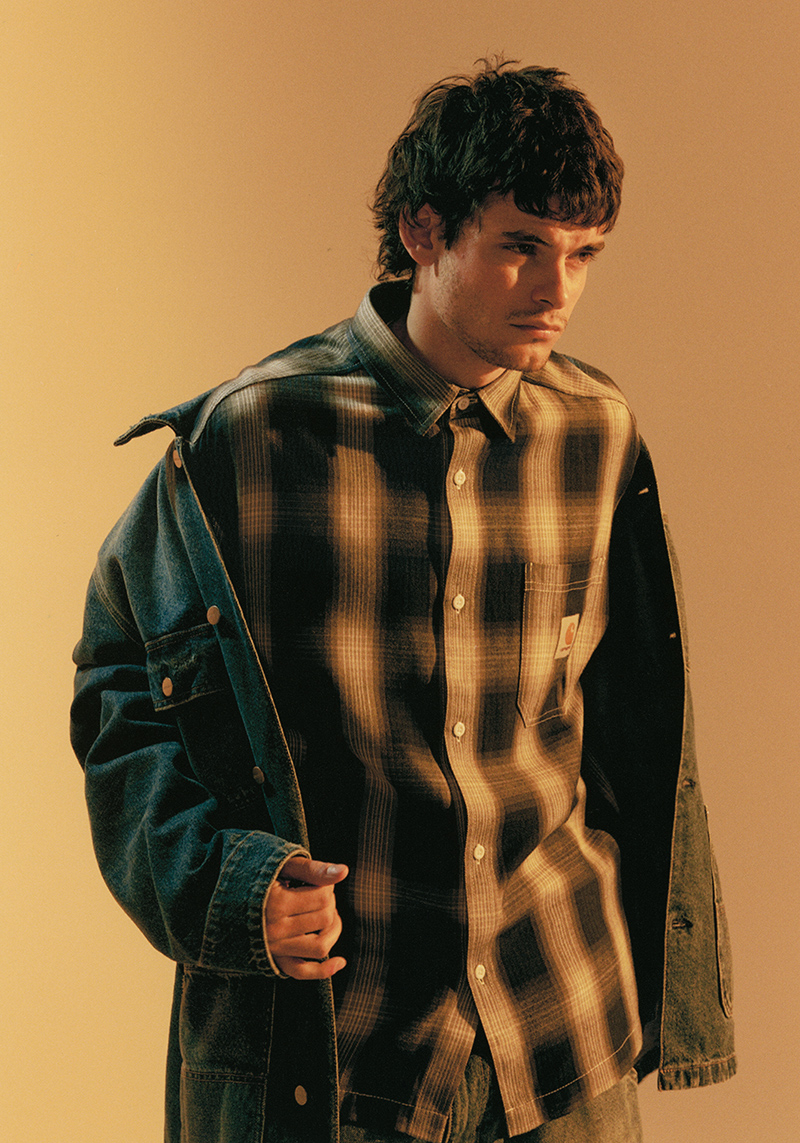

There’s a constant nod to bedroom solitude and the guitar. ,What does your room give you that no other place does?

That it’s mine and mine alone — the only place in the world that belongs to me, and where that silence is just for me. It’s the only place where no one can do anything to me, and everything that happens inside is my decision.

Your sonic palette blends Deftones, Salem, Bon Iver, or Dijon. Which of those influences would you like people to discover when listening to you for the first time?

None of those — Robe Iniesta. He’s the person who has influenced me the most and who has made me value writing the most. He’s more than half of who I am when it comes to making music.

Lyrically, there are very dark parts. ,Was there any line on the album that was hard for you to accept as truly yours?

No, not really. Although there are songs that, over time, gained more truth and felt almost like a kind of premonition — maybe that song had been written a year earlier.

Neutrogris is an essential part of the production with you. What did you learn from working together that you wouldn’t have achieved on your own?

A lot. I don’t think it’s about comparing, but he’s much better than me and has more experience, so his way of working was much more professional than mine. We’ve both guided each other and learned things from one another, but what I really like about working with him is his speed and efficiency — he never misses.

“Perdiendo el tiempo” is one of the album’s moments of light. What did you once consider “a waste of time” that you would now defend as essential?

I went through a period of isolation where I distanced myself from almost everyone by choice. I needed to focus and reclaim time. I neglected many relationships, stopped going out and meeting up — at that moment, I saw it as a waste of time. Now that I’m much better, I’ve recovered that part of me that wants to share and live moments with all the people who matter to me.

Many references on your record come from the digital, the glitchy, the broken. Which part of you do you think also works like a glitch?

Anger and rage — it’s something that’s taken me a long time to manage and will always be a glitch inside me, but I no longer let it take over or control me.

And finally: If today it were no longer “too early to be happy,” what would be the first thing you’d do to celebrate it?

Go to the beach and watch nightfall while listening to the sound of the waves.

Follow him @_macias_______