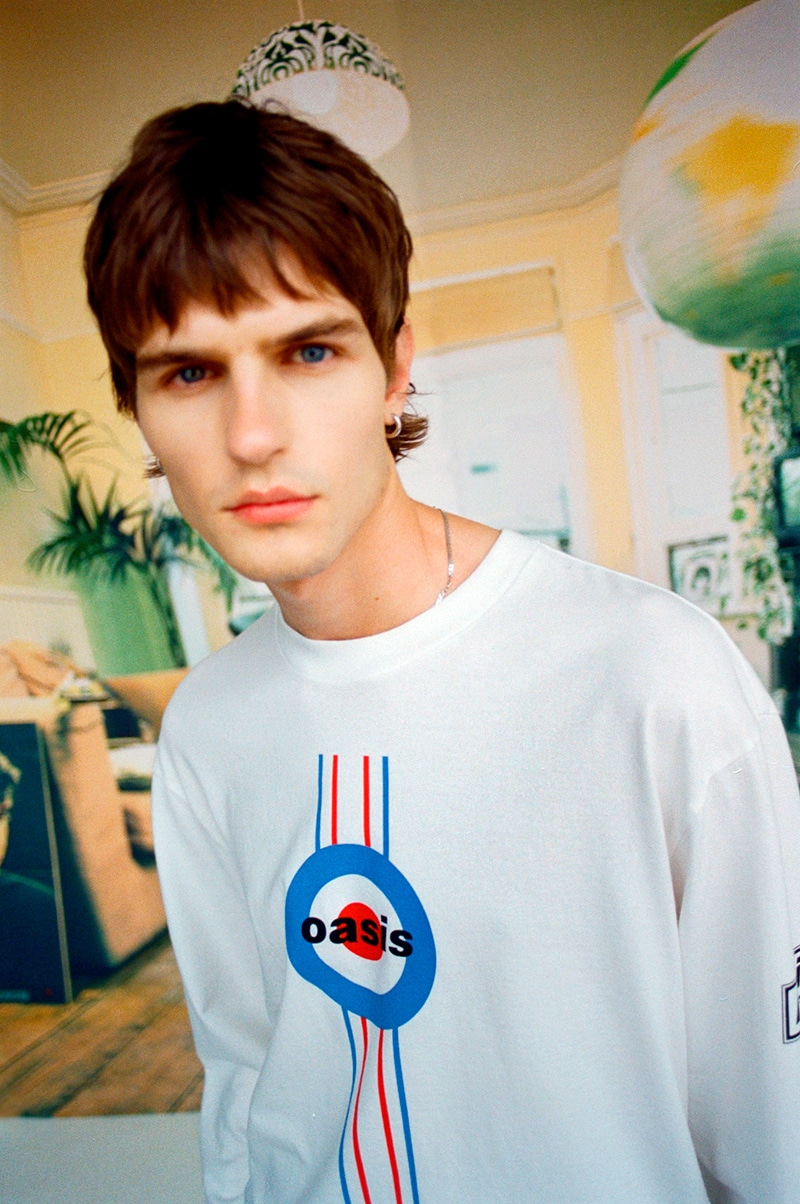

This Spring sees the third collaboration with Uniqlo and British designer JW Anderson. Featuring trench coats, bomber jackets and other pieces that conjure up imagery of British fashion, we caught up with the designer during Paris Fashion Week for a sneak preview and a bit of conversation.

This collaboration sees British heritage meet lifewear, when you were working on this project, how did you define “lifewear”?

When we first started doing this collection I was incredibly honored as I’m a Uniqlo shopper. I wanted to sink my teeth into this as its something I wear on a daily basis. What I wanted to do was re-understand clothing in Britain of what I feel is classic. I buy the white t-shirt, underwear, socks, so I wanted to imagine what those pieces would be if they were democratized. Trying to make something much simple and reduced is actually difficult. Its been a very real conversation if that makes sense.

Tell us a bit more about the inspiration for this collection.

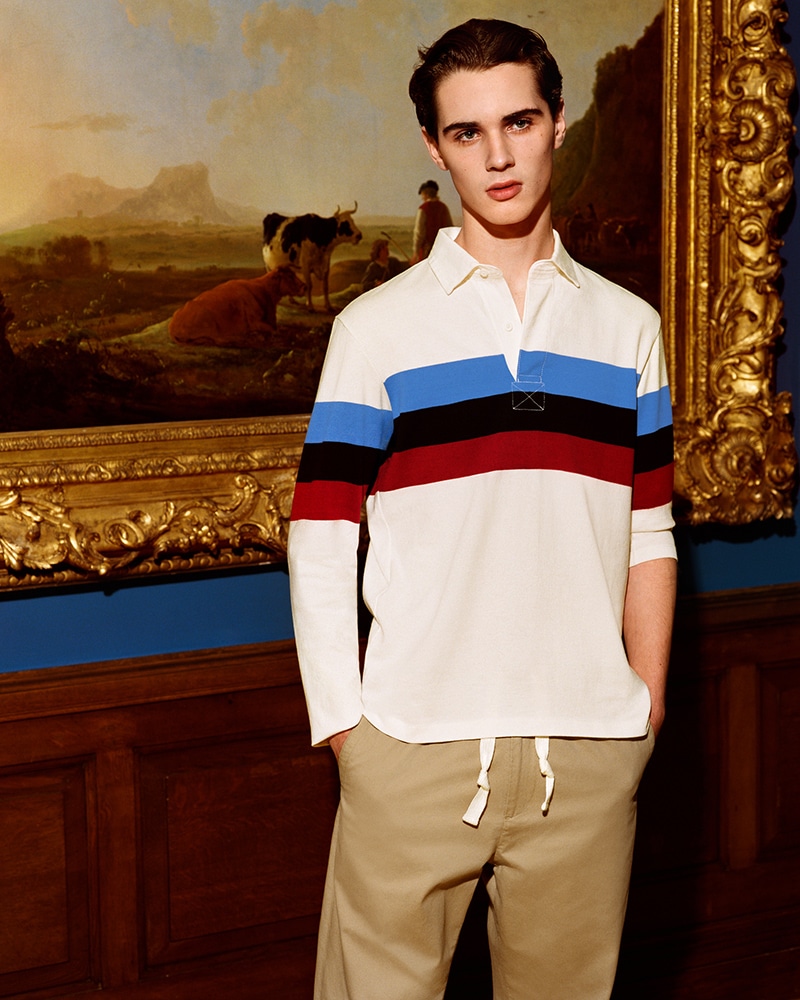

It stems from this idea of classicism in what we perceive as British. It challenged me, it was looking at where I lived. It’s looking at things that I associate. I grew up in a family that was rugby, my father was a rugby player and as a kid, I always wore rugby jerseys. For me, I felt it was inherent in terms of an icon. By during that, it was about how to translate it without a team or how do you turn it into an everyday garment. For me, each piece had to have this type of connection. Each thing also had to do with the weather, because it rains a lot in Britain. That’s why we needed the rain jacket and needed it to be reversible. I’ve always been obsessed with Uniqlo because of Japanese culture, there were things were Japan and Britain collaborated on and shared in both cultures in terms of creativity.

You mentioned the rugby print, but we also see paisley in the collection.

Paisley for “JW Anderson” and myself has been a pillar in anything I’ve done, for any brand I’ve worked for or working with. One of the first JW Anderson collections that became recognized was one that we did with paisley. I’ve always been associated with it because my grandfather was a print designer and I was surrounded by it. Paisley is very complicated to do as repeats. When Britain became a textile hub, it was an influence from the East and slowly over the years became known as a British pattern. I love a paisley scarf!

What challenges did you have?

I like to push things and that’s important because when working with Uniqlo I want to push things from the season before or try to use a fabric we haven’t used, paisley for example! That’s part of the creative process, it’s about dialogue.

You have a show this week too, how do you manage to keep them separate from your own brand, Loewe, Uniqlo, and other collaborations?

Fundamentally, the biggest thing is I enjoy it! I enjoy work, I feel like if I’m not working I’m doing something wrong. I also have very different teams that work on very different things. What everyone needs to realize is that I’m a Creative Director, I direct, I say what I want but I have incredibly talented people aside me. Without that, without the design expertise at Uniqlo or my team, we can’t produce that because ultimately I need something to talk to. Ultimately I know what I want but if I was to do every single thing, I wouldn’t be able to pull it together because I would be just engrossed in doing that. Being a creative director now is like being a curator. We are in a new era, the postmodernism of fashion, it is about how do we mix and match things, how do we create irony in fashion. How do we make fun of ourselves as well. We have to do what works for us as well.

You work with three different teams, it’s a lot on board. Did you look into the Uniqlo supply chain and is that important to you before you sign on?

Its important to anything I do, and it’s becoming more and more important. Sustainability is not something you can click your fingers and do tomorrow. It is a cultural change and I always believe you have to do everything that’s physically possible. I feel that brands bit by bit is trying to do fundamentally massive changes. It’s very difficult in terms of demand. We are a “want” culture and companies have to catch up. What’s amazing at Uniqlo and JW Anderson is visiting factories because that’s our responsibility. Today, we are at a very odd moment where there is a reality and non-reality, there’s a recreational outrage about things, for me its where we all have opinions on things and not solutions. For me, I don’t work with anyone who doesn’t have solutions whether its supply chain or gender gap.

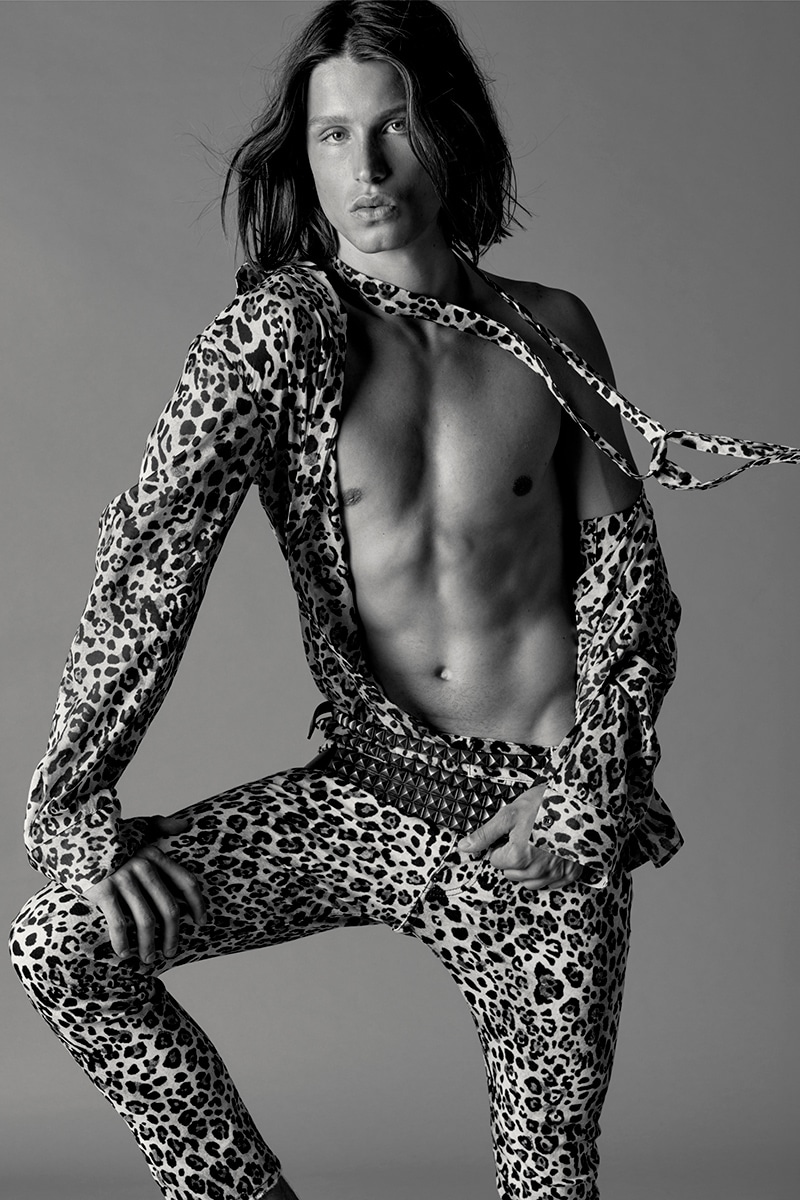

What is it with you and unisex?

I don’t like that word. I feel like in the 70s everything was unisex then fashion got a hold of it and turned it into a trend like the androgyny in the 90s and we sucked the life out of it. I’ve always been obsessed with the idea of garments for the garment’s sake. For me, its this idea of a shared wardrobe. I have this image of the white shirt, one on Robert Mapplethorpe and one on Patty Smith, they mean completely different things but are the same garment. Is that unisex? I don’t know, or is that just choice ultimately. When I was a kid, I remember being fussy about zips, like does it zip in the women’s direction, we don’t think like that anymore.

You mentioned your father played rugby, rather than saying unisex, do you think pieces need to have a certain athletic or outwear appeal that makes it genderless?

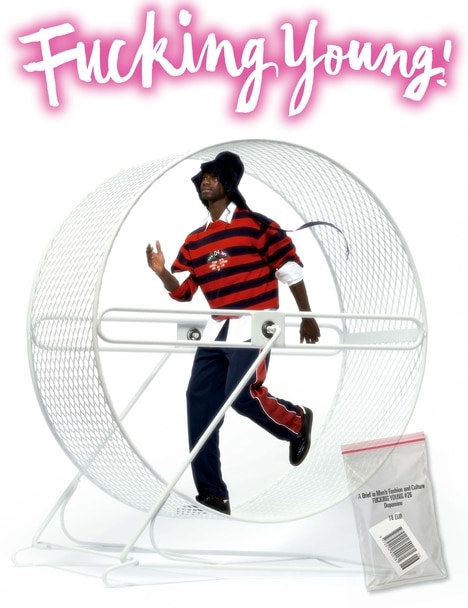

I always think it must come from somewhere. My father played international rugby in the 70s and 80s and in those days you would be given a kit made up of hundreds of pieces. My father is 6’6 so everything is huge and we wore it, but my grandmother wore it too because it was just functional. I find it very difficult to do sportswear because my entire childhood was that. In this collection, we put a rugby shirt in because I used to wear that as a supporter of my dad but at the same time they were incredibly uncomfortable, now they are made by major companies that have the technology, but I wanted something that had nostalgia but didn’t have polyester.

You mentioned the democratizing fashion, why is it important to be price conscious?

The only designer thing I bought growing up was a pair of Tom Ford’s jeans after saving up for like two years, I wore them for like a week and they didn’t fit and I also shopped at TK Maxx. You didn’t have luxury fashion in Northern Ireland, there wasn’t like a Prada or Vuitton. It was about being resourceful. My sister doesn’t work in fashion, she’s a pharmacist, and she’s been influential since day one. I wanted to try to make something good for under a hundred pounds, which is still a lot of money. Which is why I like to do my brand which is one price demographic, Loewe, which is another and I like to do Uniqlo because ultimately whenever someone goes to a store they have to leave with something whether it’s a sticker or fanzine which is free or art that they’ve never seen, there has to be something because I remember going to Dublin to the Vuitton store just to get a catalog. There was a big barrier in luxury where that has all changed now. That’s why I like doing this project.

Finally, why do you quirky has been such a success lately in fashion?

I think it comes down to irony. We have been quirky for a while and it’s going to change. In the last five, six years, we are at a moment where we are subjected to so much imagery and we are subjected to so much jargon. In a weird way clothing at fashion shows have become like tumblrs. Anything could exist in fashion, we are editing and putting together clothing in a completely different way than we ever have, we need instantaneous things. Things have become louder more weird because we have to make sure when we are scrolling through our phones that we go “oh great, that’s interesting”. We will still buy a white t-shirt but most people won’t stop on that.