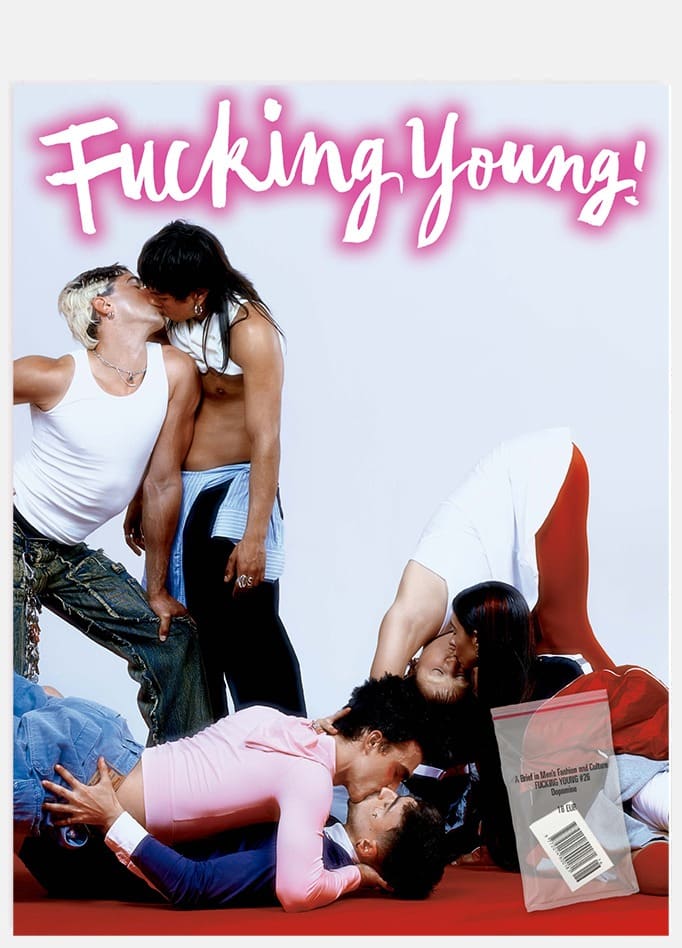

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, in support of the BBK, brings us American artist Paul Pfeiffer‘s largest European survey to date “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom”. In our media-saturated society, where each day is increasingly consumed through a screen, Paul deconstructs the apparatus of image-making that shapes our perception of ourselves and leads to the formation of collective identity while uncovering the mechanisms that constitute our perceived reality.

Pfeiffer’s works are in continuous dialogue with multiple generations of narrative structures and image makers from Dada to A.I. His works can be seen as the catalyst or precursor to meme and gif culture. Stories become a prototype for an idea of transformation, intercepting what it means to be a person in society along with what brings people together is a universal theme, whether it’s sports, music, nationhood, politics, and connectivity through the architecture of a stadium or arena. The exhibition design is a core component to experience Paul’s work covering 25 years.

The exhibition sees us encountering footage as sculptures from small projections, and LCD monitors, to room-size installations where you find yourself physically looking very closely and intimately at works or from a distance. Still, something feels off, like glitches, erasure or camouflage, repeated loops, immersive sound or light, and most of all de-normalizing the normal provokes a full sensory of engagement. Following this individual and shared experience of “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom” within the Frank Gehry masterpiece which is the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, we met with Paul to continue the dialogue.

The Long Count (Rumble in the Jungle) (still), 2001 Standard-definition video (color, silent; 2:51 minutes), painted 5.6-inch LCD monitor, and metal armature © Paul Pfeiffer, Bilbao, 2024.

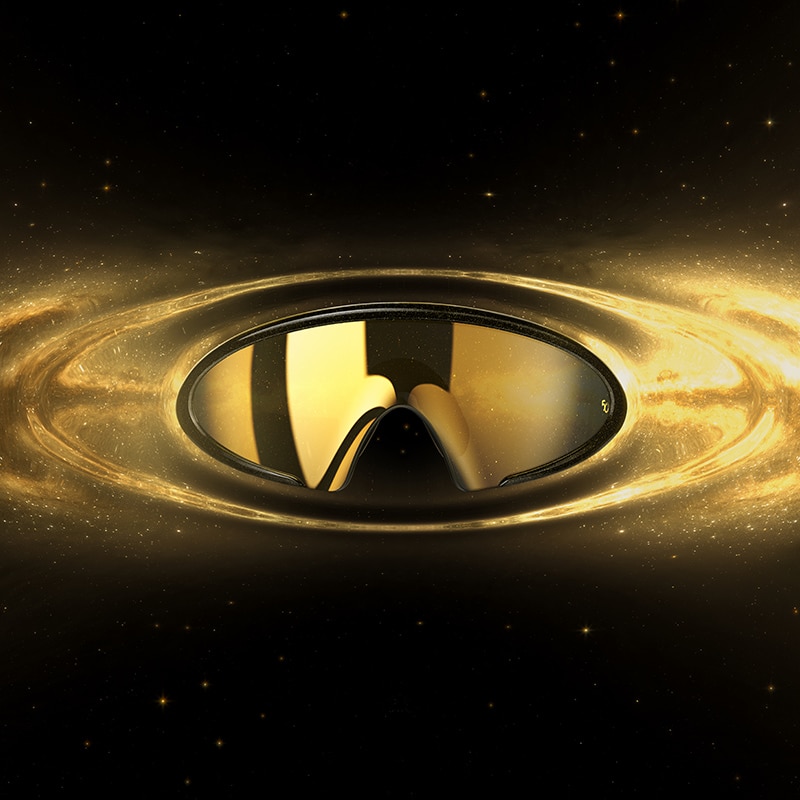

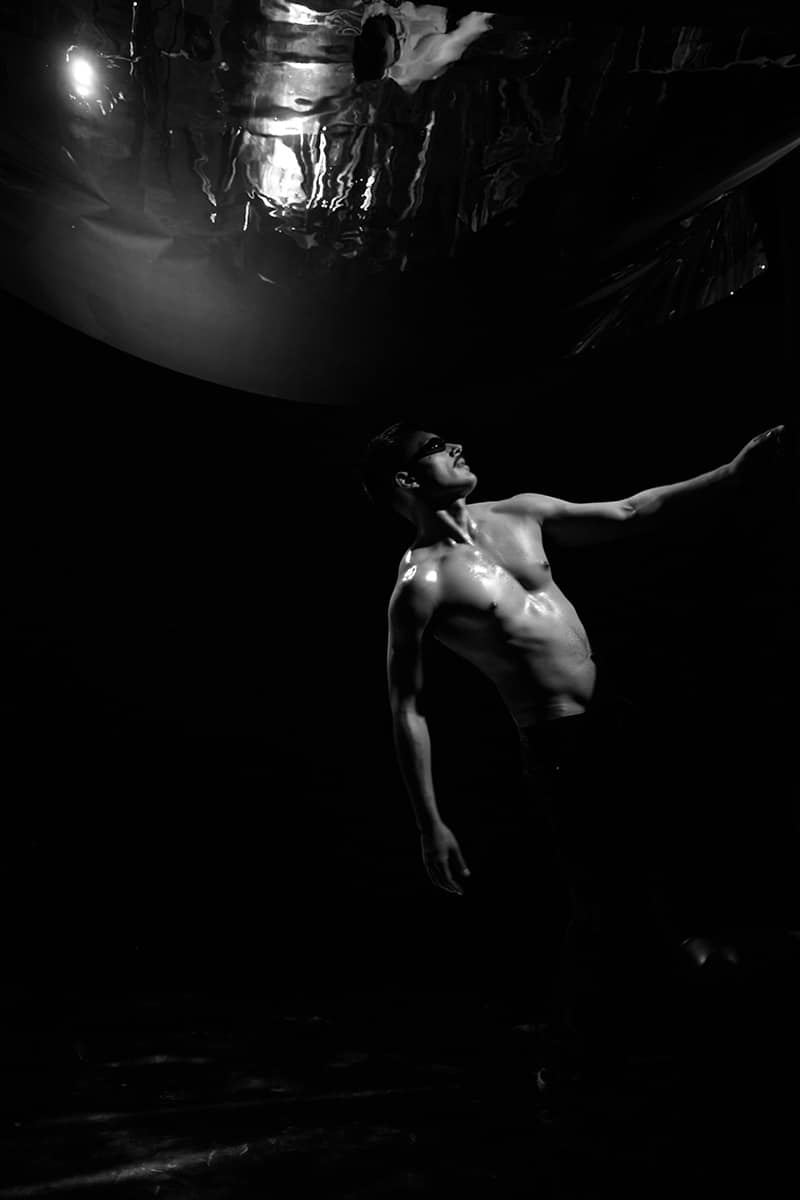

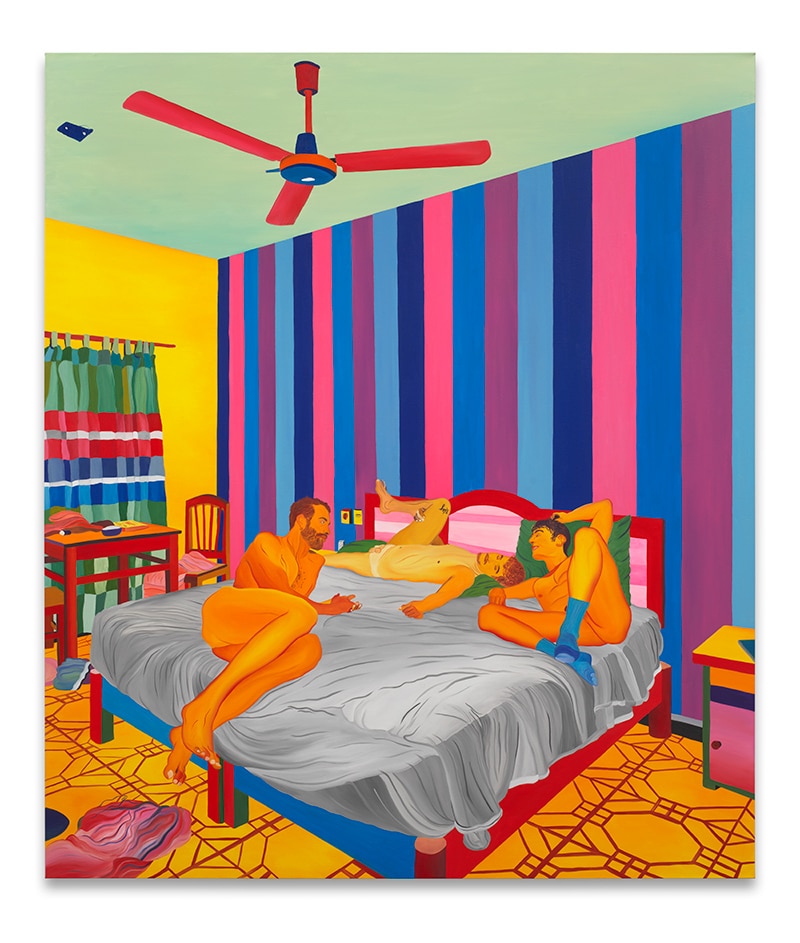

Red Green Blue, 2022 Single-channel video (color, surround sound; 31 min., 23 sec.) © Paul Pfeiffer, Bilbao, 2024

“Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom” at the Guggenheim Bilbao is your largest European survey. Experiencing your piece Red Green Blue, felt very meta as we were watching people on the screen watching people, I looked around the encompassing room as we were sitting on stadium-like seats watching the piece and I was watching the visitors. This was not the experience I was expecting from looking at stills of the exhibition on screens alone at home. Do you think about how you want people to experience your work?

That’s funny because we both just came from the gallery, and I just suddenly had an image related to what you’re saying that, in a way, you’re seeing people at a 90-degree angle, or you’re standing in front of them and they’re looking somewhere else. So, you are watching other people watching something. As though they can’t see you, in a way, like seen by sin. The position that you occupy is one of an invisible watcher, unnoticed as people are immersed in a certain state of attention. You’re watching them. In a way like, “When is that perspective?” You’re like the Watcher. This does have a connection to horror movies because, in a way, the Watcher in horror movies would be a non-human entity, who’s watching humans, in their human lives.

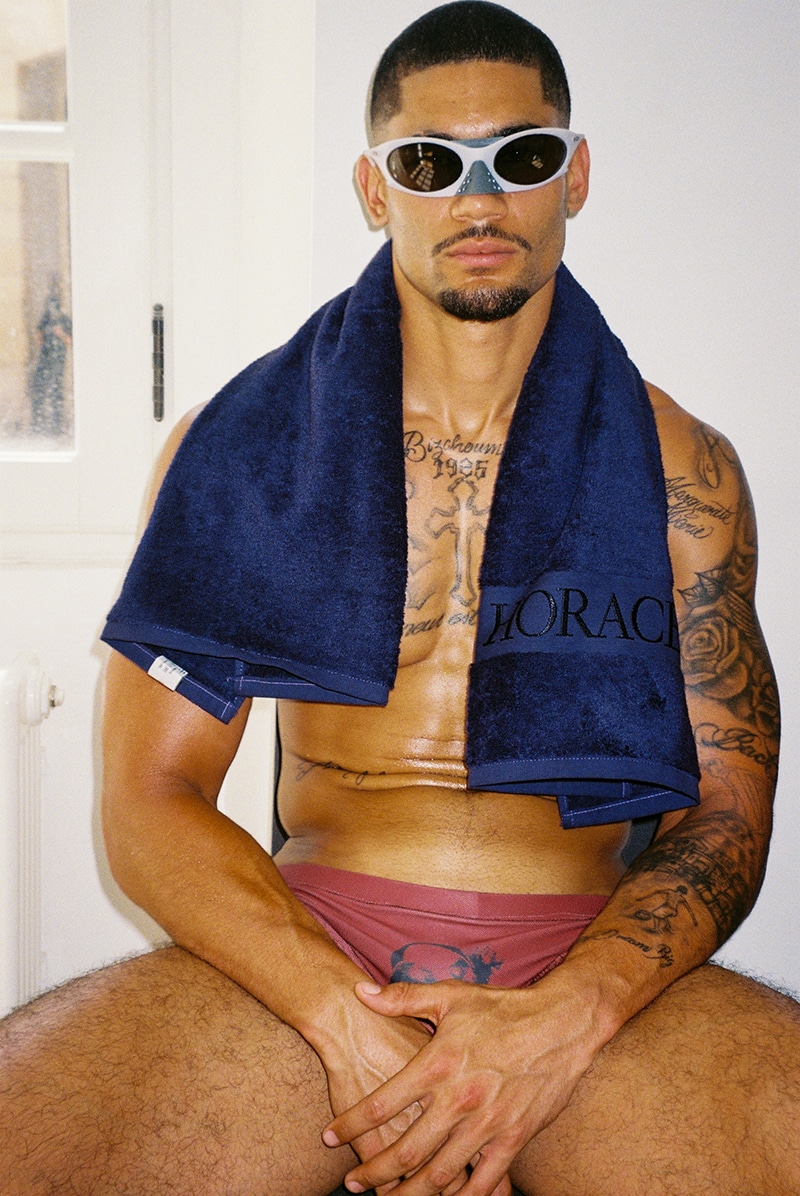

Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 2000 Mixed Media © Paul Pfeiffer, Bilbao, 2024

Right Monitor: Caryatid, 2003 Digital video loop (color, silent; 50 sec), chromed 9_inch colorCRT monitor, wood, and Plexiglas © Paul Pfeiffer, Bilbao, 2024

I felt a horror element or pipeline between Poltergeist (Spoon) and Caryatid (2003) a digital video loop of a hockey cup trophy as if suspended by Poltergeist. There are references to iconic films from Self-Portrait of a Fountain (a sound stage recreation of the shower in Psycho with the film cameras replaced with surveillance cameras), The Pure Products Go Crazy (a looped digital projection that replays less than a second of a scene from the 1983 movie Risky Business), to even the title of the exhibition referencing Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, the most expensive movie ever made while being an epic religious drama. Was film your initial interest that led to art?

I’m trying to simulate or recreate a kind of original experience that I had. That was an experience that is hard to describe because of the way it happened. I was a child and it was an early discovery of perceptual imbalance. I woke up in the middle of the night, you could say I had a nightmare, but essentially things did not feel correct. It was a little bit like an out-of-body experience. It lasted for some time and then it went away and it left an impression on me. I didn’t know what to make of it. I was 10 or 11 years old in the mid-70s and living in faculty housing at the American University in the Philippines, a Protestant University. The movie, The Exorcist just came out, I didn’t see it but all the adults were talking about it. The closest thing that I can associate with what I felt and experienced was what I was hearing from others as being possession.

Did overhearing about possession stay in your subconsciousness?

It was palpable, it was in the air. The Exorcist is considered a classic film, what I came to as an adult was to study it. I wanted to understand why it freaked me and other people out. I’ve heard it described as one of the first movies to consciously employ techniques of subliminal suggestion borrowed from advertising. For example, there were scenes in which planted within 24 frames per second of the film are individual frames of a ghostly face. Because it’s only one out of 24 frames it potentially goes by subliminally. This was an effect that was experimented within that film and maybe more importantly, the film in 1973 won one Academy Award and it was for sound design. There are things going on in the film that had to do with sound production like the effect of a young girl speaking in a bizarre voice that’s no longer their own. When studying thematically within, the Jesus of the film is discovered to be a number of voices in reverse. There’s a remarkable coincidence that has to do with the early experience that I had, which had both a religious or spiritual dimension to it of mythmaking and a technological one. What I had experienced in a way related to what was generally agreed to be a major innovation worth giving an Academy Award to, where tape loops were used for the first time in which human voices were being played backward via post-production, recording processes to create an effect that could be associated through a religious metaphor with a non-human kind of ghostly presence. It opens up a space between identity and voice as a kind of manipulable relationship, both technologically and, in a way, ontologically or spiritually. I feel the key interest in the horror genre is that it opens a space where psychologically and philosophically you could inquire about subjectivity, subject formation, speech acts, language itself, and then the mechanical reproduction of language. The point is these things are not identical and stable, they’re actually very plastic and manipulable, can be broken down into channels, and can be synced and un-synced to create all kinds of effects.

Aesthetically, what’s led to is a practice of playing in the editing room and physical objects, with immersive spaces to produce. My hope is for the viewer to finally get the answer. To reproduce aesthetically something that I experienced myself has been an inspiration to me for 25 years.

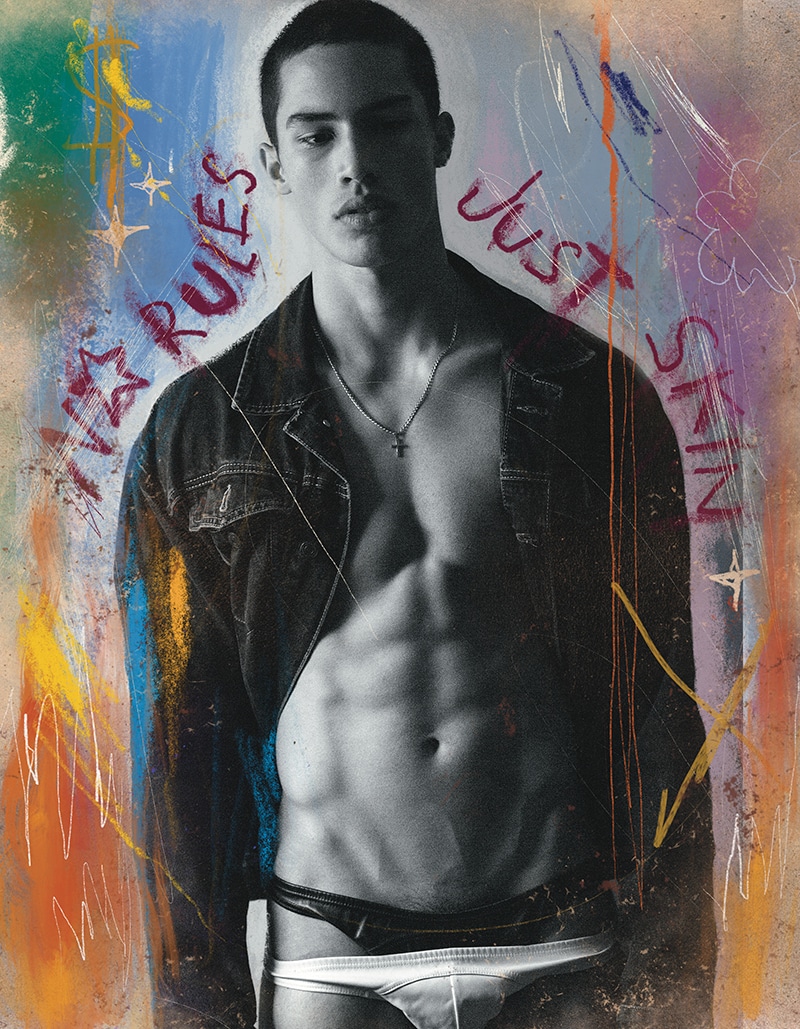

On the subject of horror and religion, Incarnator (2018-ongoing) stood out to me. You worked with encarnadores ( from the Latin word meaning “to make flesh”) sculptors in Spain, the Philippines, and Mexico, where carvings were modeled after pop star and born-again Christian Justin Bieber, conflating religious icons with contemporary celebrity worship. The craftsmanship is so beautiful, yet there’s also an extremely macabre element to it especially reflecting on his life in recent years, events and antics have a different meaning when viewing the piece. You draw upon certain images that live rent-free in your heads, whether it’s a movie or a celebrity. Going back to subliminal advertising, what felt shocking to me was seeing the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the erasure of logos, franchise branding, and no signs of advertising. What has been living rent-free for my mind over the years was Nike’s “We Are All Witnesses” campaign.

That’s so religious, right? Advertising in a way is similar to interpretive commentary or explanation cards in that they tell you what to think about what you are seeing, subliminal or not, they give you a predetermined logic for what you see. By removing the commentary or the subtitles, you’re made to flow free and maybe have to work more to think about the meaning of things when the commentary is removed.

My own experience of sporting events is the amount of talking that happens over it, telling you obsessively what you’re seeing, what’s happening, and what the person’s going to do next; everything is about stats and commentary until it becomes a background noise which at the same time becomes naturalized into part of the sports scene. Simply taking the commentary out, like taking the advertising out, is potentially uncanny because we don’t see these images this way.

It brings me to my next question about Empire(2004). Art can be very confrontational and here we’re confronted with a wasp that you captured for 90 days and recorded directly to a hard drive, the video installation sees it projected in uninterrupted real-time. It mediates on organic and technological. The wasp didn’t know she was being filmed, but it was creating something and it made me wonder, do you feel that there’s a purpose to creating art if nobody sees it? Would you have filmed it if there was no intention to share it?

I do feel as an observational filmmaker, using the camera to observe is almost like meditation and induces a different state of mind. So does editing, to edit frame by frame could mean working on an image pixel by pixel for days. In a way to do that is not a painful experience. If you get to be at an editing Suite with no distractions you enter into a different a kind of editing frame of mind and get lost in it, in a way that’s actually and intentionally pleasurable. At the very least induces something like an alternate state of consciousness in itself. What I would say is that there is a very specific intention to want to make images that other people are going to see. At the end of the day, my purpose is a desire to be part of a generational conversation to be part of a conversation in general. I’m not doing this for myself, I’m doing this because I want to be part of a conversation and that’s what art is to me. I choose to focus on scenarios that have to do with collective identity. I want to be a part of that conversation during my lifetime, and in a way, I want to leave that little part of myself in the record of my generation. I also feel like we’re going somewhere together, there’s an individual journey page with takes and then there’s also the collective journey that’s happening, that’s meaningful to me.

Do you feel that there are expectations that come with being a successful artist today and how do you know if you’re successful at what you’re trying to do?

Some of it is related to this idea of being part of a conversation led by curiosity. It’s a privilege to be able to present work here, the process of presenting works here, getting feedback, and also new directions like the local football clubs and the bullfighting scene which at this moment are super inspiring, through the museum I’m getting to meet civic figures involved in these scenarios and being given privileged access to potentially work with them.

In regards to social media, I’m a very erratic social media user, I don’t like the idea of posting indiscriminately and to me, that’s too fast as a producer. I like slow images and I find the speed of social media too fast to participate regularly. I believe that there’s a simultaneity of say new media and old media, there’s a balance between them, and that it’s not just about, you know, getting lights or follows. I would say that it’s a little like the images, living rent-free, when things go viral, I want to pay attention to that because that’s telling me something.

© Paul Pfeiffer, Bilbao, 2024

Paul Pfeiffer “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom”

At the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao until 23 March 2025 in support by BBK