If you were to take a holistic approach to fashion and diagnose its many faults, how would it look? Philip Huang explores the knowledge of the past on hand-made textiles and accessories to look at the future. Using only natural dye from indigo plants and organic fibers produced in the Sakon Nakhon region of Thailand with artisanal techniques that have been passed on for many generations, the brand in many ways is also a fashion think tank. While creating organic pieces that belong in a wardrobe, not a disposable season, Philip Huang (also one of the first major Chinese-origin models) and co-founder Chomwan Weeraworawit, are also sharing wider dialogues and conversations. We got a chance to be a part of one.

You’ve been on such an exciting journey! Let’s place the start at modeling. How did your career begin and was it as you imagined? If I am correct, you also have a degree in engineering, so I’m guessing you didn’t plan on modeling.

I did Engineering at Drexel University and part of it required practical experience already in engineering so after I finished university, I thought I would give myself a year to do something different so I went to NYC. I wanted to travel and I thought modeling would be a way for me to do that so I started modeling and well, I guess I never looked back and here I am.

What did you learn about the fashion industry in those early years? Were you ever interested in the supply chain and transparency of the brands or was that not part of the discussion at the time?

It was amazing really to spend so much time with these talented visionary creatives, I was really lucky to be there to see how things worked. I would show up and we would do fittings but what I saw also was the process and I thought this was really fascinating. You see stylists come in with racks and you’re like whoa, this is overwhelming for me to see all this. I’m like, damn do I really have to try all this on? And now I’m on the other side and it’s cool, makes me appreciate more all the work that goes into it. Those years taught me a lot, in a way it was like attending design school, I would always ask questions. And also, all these guys around, they’re all from different parts of the world it was interesting to see what they were wearing. It gave me a lot of inspiration as well.

Supply chain and transparency were not really part of the conversation in the early 2000s when I started, but when I started my own brand, I think it was just being in those circumstances and my interest in how things are made. The engineering background probably has something to do with that, how things are made, the process, from the very start it really made an impact on me, working in the villages, learning about how things are drawn from the land. The route that we ended up taking is not “traditional” in the fashion production sense, we were literally working side-by-side with our suppliers – with the dyers in Isan and with small ateliers in Bangkok. As for supply-chain transparency, by the time I started the brand, a fair bit of work had already been done with transparency and awareness raised on the importance of this. Working in a transparent way, knowing our supply chain, what it’s made up of, it’s very much in-built into what we do. For example, working with natural indigo, if you don’t know the composition of the fabric that is being dyed, it can change how the dye reacts to it and the color and the color fastness and everything, so for us supply-chain transparency is very much part of the process.

As a model, you were exposed to casting agents, stylists, designers, ateliers for fittings, etc. Did you see first-hand the lack of diversity and do you feel fashion is taking the right steps to change for the better?

It’s good to see the changes that are taking place today, that there is a conversation around it – as a model, there were always guys from all over the world and because of that, there is less judgment amongst all of us. Also, there were vocal and supportive allies that promoted greater diversity in fashion and I’m really grateful for them.

For years the industry has been criticized for cultural appropriation, many creatives defend themselves saying its inspiration or homage to a culture. You co-founded the brand with your wife Dr. Chomwan Weeraworawit-Huang, while she was getting her doctorate at King’s College London, her thesis emphasis was on intellectual property and textiles. Can you please describe the correlation with the industry and what you learned from her?

You know it’s funny, one day I had a look at Chomwan’s thesis that was sitting on our bookshelf and read her hypothesis and what her intention was in doing her PhD, and then it all made sense to me how we shaped the direction of the brand the way that we did. Of course, there is the production and the process aspect that I am really focused on and then there is the bigger why – and that in a way is what Chom’s research and conclusions inform – maybe our brand is a little bit like her guinea pig too. The basis of Chom’s thesis is that intellectual property in the context of fashion and textiles can be used as a tool, especially in developing countries where things are still handmade, she refers to artisanal fabrics, natural dyes that are protected by geographical indications and traditional knowledge. She talks about intellectual property works – so a photograph, a film, a piece of writing, music, all that is protected by copyright, and then there are trademarks, so the brand logos, etc, and that these must work together. The trademark houses not just the product but also all these “works”, it’s the content that explains what the products are, what the textiles are. And when it relates to villages and traditional wares and artisans, she argues that the creation and protection of these works are key to creating value in the villages. For example, if a textile is protected by a geographical indication (GI), but no one knows what it is, what it looks like, who the artisans are, what the terroir is like, then why does it matter? That is very much the approach we’ve taken with our brand, we must tell the stories and the brand must function as a platform and if it works it can actually play a huge roll in development. And development does not mean big factories but rather small, specialized, high quality weaving groups and co-ops that can pass on the know-now to other generations.

Hand-dyed, handwoven indigo cotton is protected by GI, but not all villages have the GI as they have to prove that the technique and terroirs in keeping with the traditional method which qualifies for the GI, to begin with. We believe that it is really important to properly identify, tell the story of and credit the villages with the work that they do – not only because the ethics of it – because this is what enables the legal instruments that exist to help them to really work, after all, if all this is not communicated then how do people know about it? So going back to cultural appropriation, I know it’s a very delicate topic, here in Thailand, for fabrics to be exported around the world, to be worn by people of other cultures, it is actually a source of pride and also additional income – but it’s a fine line – to expect that these goods are cheap or of lesser value, or that they can be taken and not attributed to the people who make them – I mean, that’s not really ok is it? It’s about context and intention, I know for the villages we work with it is an exchange, it is a constant dialogue between us and the weavers and dyers, the Indigo Grandmas. What Chom’s PhD really instilled in what we do is the responsibility to tell the stories that as a brand you can be so much more, you can be a platform, a vehicle that can bring people closer together.

At some point, you become interested in natural dyes. While synthetic dyes have been polluting waterways for years because of fashion, did you ever hear that discussion or did you find a lack of it that encouraged you to investigate?

I think it was in 2014 when we decided we wanted to try indigo dyeing, I can’t remember what exactly sparked this curiosity but it happened at the same time even though I was in NYC at the time and Chomwan was in Bangkok. I did my first workshop in Brooklyn with Biaisou and Chom did hers in Chiang Mai at Studio Naenna. From Chomwan’s research she knew that there were natural methods out there and she wanted to explore them, and I just really loved the blues I saw in Japan, the natural indigo blues, and wanted to learn more. After we started dyeing with natural dyes that’s when we became much more aware of the damage that inferior quality synthetic dyes do to the environment. I guess once we got to know the alternatives, and learn that they are just as awesome in color if not more because they are living dyes, that we looked more into the benefits of natural dyes and the disadvantages of synthetics. Wastewater management is a real thing and the wastewater from synthetics can be so harmful to all that is around it and it must be treated properly and inferior quality dyes damage, not just the environment but is harmful to the dyers.

Your brand was founded on a rooftop in Bushwick and you recently relocated to downtown Bangkok with your family, what triggered the move and did you find it risky?

We moved back to Bangkok because were living in NY with a young child, Aree was barely 2 at the time and we found out that we were having twins! So we thought, why are we doing this in NY when Chom has family in Bangkok and I do too (my uncle moved here 30 years ago and one my aunts as well) so that’s what we did – we left NY.

For Chomwan, it’s home and in a funny way, I always felt a connection with Bangkok because of my family. When she was pregnant, I was still in NY, packing up and that’s when we made this indigo connection. I think 8 weeks after she gave birth to the twins we took our first road trip to Sako Nakhon and that changed everything. This realization that in Bangkok, you can still get things made by hand, that you can drive out of the city and be in the countryside and that you can learn from artisans. It wasn’t risky, it opened up a whole new world and up until COVID we were very much living between Bangkok and NY, some years Chom is there more, others I am but I’d say until this march we were still 30% – 50% of the time in NYC.

Tell us about the Indigo Grandmas?

The Indigo Grandmas of Sakon Nakhon are the grandmas and aunties we met during our journey to Sakon Nakhon. These ladies pass on the knowledge of indigo. Today, it is not only the grandmas who dye and weave indigo textiles but a whole new generation of dyers who believe in preserving this ancient craft. They are the guardians in a way and they learnt from their mothers, so many stories they have to tell. They are the experts and our teachers, the grandmas, and our friend Mann (Prach Niyomkar) who is a first-generation dyer from Sakon Nakhon.

Would like to see any of the big houses outsource their indigo dying to you and your artisans at Sakon Nakhon Indigo?

I think this could be really interesting – what we believe is that indigo belongs to the community, it belongs to the land, the grandmas, the next generation and for it to thrive and for it to evolve – we must work together – it must be compelling and cool for young people to come back from the cities and become artisans. I think it would be really cool to do collabs together with bigger houses – imagine developing shades together, or even new Ikat patterns and things. I don’t think it is necessarily about turning Sakon Nakhon into a big indigo dyeing outdoor factory, I think it is more about the collaborative process – working together with the dye to create exceptional products and evolving the craft, we’d love to be a part of that conversation.

We talk about fashion, and in particular fast fashion, in regards to the contribution to climate change, but rarely do we look at the growing gap of wealth distribution. How do you map the two subjects simultaneously?

Chomwan: When a country is about to embark on fast-paced economic development and move away from primary industries like farming and fishing they look to fashion and textiles, the repetition and basic nature of fast fashion and the labor needed in factories to produce it means that it can help towards faster economic development. This is what was seen for years through SE Asia before China became a factory to the world. Interestingly, this was the starting point for my PhD, fast fashion brought development fast, and what that did was hasten the speed of climate change with the pollution from these huge factories. So what it did was effectively elevate people’s lives, overnight you had billionaires and people who were living on minimum income (or not at all if there is natural strife or something that affects farming practices) from farming working in factories and being able to send income back home to support their families. The crazy thing about this though is that money is being paid and whilst laborers are making enough to send home, this is a far cry from what the factory owners and brands are making – but then again is this not better than working at on a farm? It’s a hard question. And I don’t know if there ever the perfect answer, but knowing that there is a correlation is important. On a simplistic level, the gap gets smaller, the planet suffers; the gap gets bigger the planet suffers. So the question should be how do we reduce the gap and have the planet suffer less – Philp and I think the answer is going back to the land and re-activating in a sustainable way old traditions and utilizing resources that are overlooked upon to increase income and reduce that wealth gap that does not rely on fast fashion.

You had plans with Waris Ahluwalia to launch a t-shirt collaboration with indigo and Waris’ teas (as a natural dye) but decided to shift production to masks for COVID instead. How did you two meet and how did this conversation of dye come up?

Chom has known Waris for years and when we first got together and she moved to NY he was one of the first friends of hers she introduced me to. Waris is an explorer and naturally inclined towards craftsmanship and artisans – when you look at what he did with his jewelry back then and now HOUSE OF WARIS Botanicals – you can see he has a real passion for things being made by hand and nature. So natural dyes, in particular, indigo came up way early on, so many projects we’ve talked about and he wears the indigo well. So when he was preparing to launch his teas it naturally came up that we should do something together using his teas as a dye.

I would say that collaboration is part of the brand’s DNA. Your wife Chomwan joined forces with the Thai powerhouse team cinematographer, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, (Call Me By Your Name; Suspiria, 2018) and film editor Lee Chatametikool to create a short film entitled FINDING OASIS SS21 – SAKON NAKHON INDIGO, how did that collaboration come about and where can we see it?

Chomwan: When we decided to make a film, I called up my good friend Lee Chatametikool and explained to him exactly what I had in mind, what we needed it for and the mood – the everything I guess. I told him about the imagery that inspires me, the Isan that we saw long before we took our first road trip there, and how the films he edited of Apichatpong’s so deeply inspired us on this journey. So he suggested that I call P’Song (Sayombhu Mukdeeprom) as the films that I was so in love with he had shot. The thing is the stills that make up our moodboards that make up my fantasies about our brand are stills from P’Song’s camera. I knew this and thought, really? Would he do it? Lee encouraged me to give him a call as he felt P’Song would be the right fit. So I summed up all the courage I had and gave him a call, I’d met him before on a couple of occasions but we had never spoken. So anyway, we spoke, I explained to him in a couple of minutes what I wanted to do (probably in one breath) and he said, yes, I’m interested, I want to do something that helps support Thai textiles, it’s important. So that was it. I called up a friend, P’Beae Cattleya who is a super-producer and told her about the project, this was 6 days before we left for Sakon Nakhon and she made it happened, with a digital bolex and a whole crew intact, exactly 1 week after they lifted COVID restrictions (though there were measures in place when we filmed of course). And that was it, P’Song was amazing, the whole crew was, then we came back to Bangkok and have been in the editing suite with Lee’s team and spending hours at White Light Post.

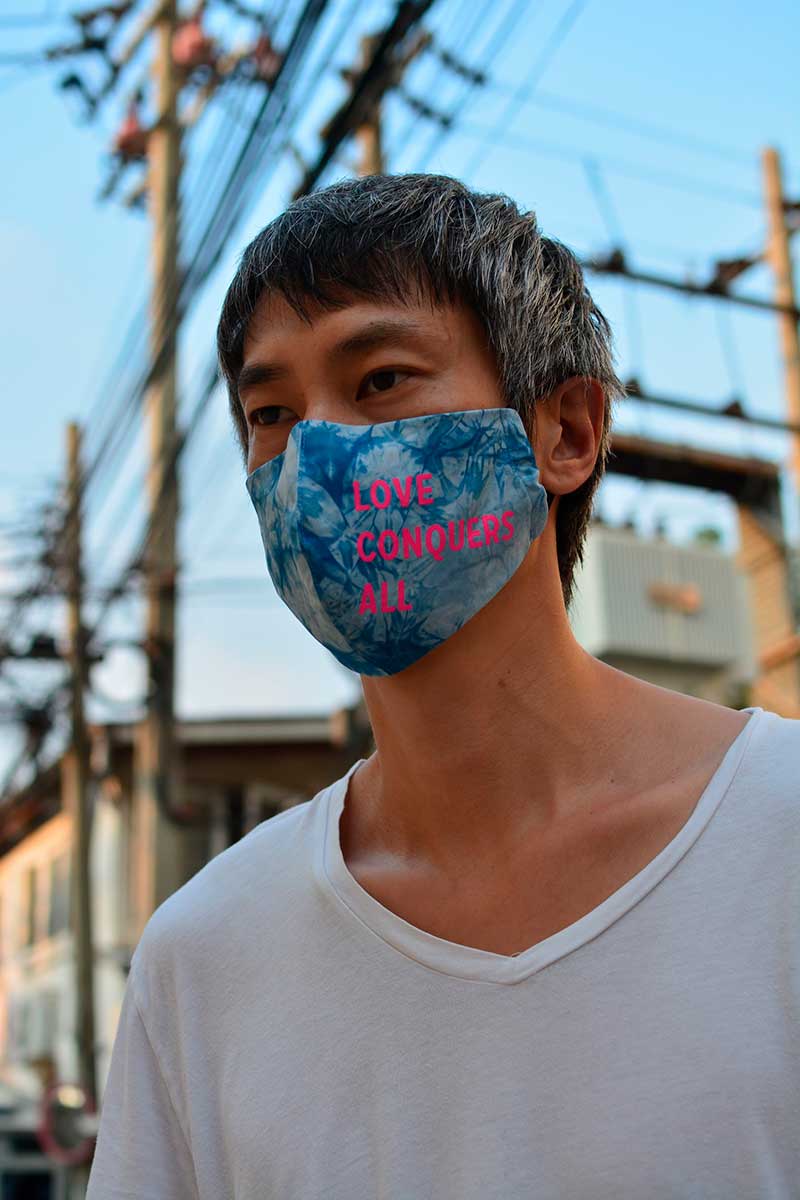

Additionally, your friend, artist Sandro Kopp (Tilda Swinton’s partner) suggested that you do LOVE CONQUERS ALL tie-dyed tees, that you are planning to launch later this year. During this time of turmoil, what makes you optimistic that the message will ring true? And where should we place our efforts to ensure it?

Chomwan: A couple of years ago when Tilda and Sandro were here in Bangkok, I shared some t-shirts with Sandro so he’s familiar with the tees and this summer he ordered some tie-dyed ones and then after we posted pics of our masks with Waris he suggested that we should do a t-shirt! Right away we talked to Waris about it (they are close friends too), and I know Waris is looking at some design ideas already and we will be launching this together soon. We are optimistic because love does conquer all, the only thing that will get us through this is love, compassion, and understanding. There are so many things that are broken, that are upside down, and it’s not going to be an easy fix. It seems like the world is addressing it now after a 3-month long sleep that seemed to have awoken so much, and it is indeed turmoil, so in that turmoil, we all agree amongst us that a word of hope, of light, is needed so that we can keep focused and keep positive while we continue our fight against injustice, which takes so many different forms everywhere in the world.

We think that communication is key, raising awareness so that the injustice can be brought to the fore and change can happen. It’s really hard to fight what is invisible.

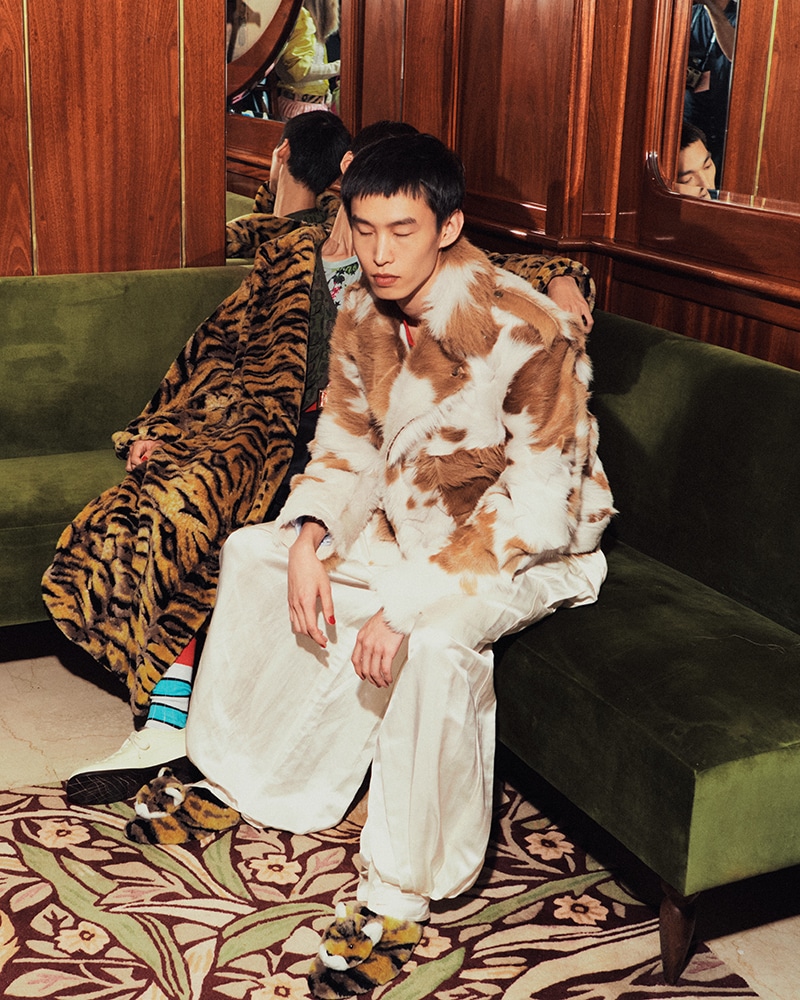

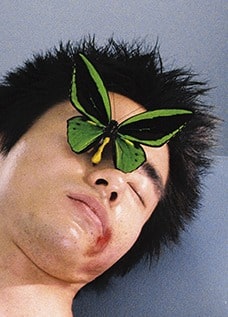

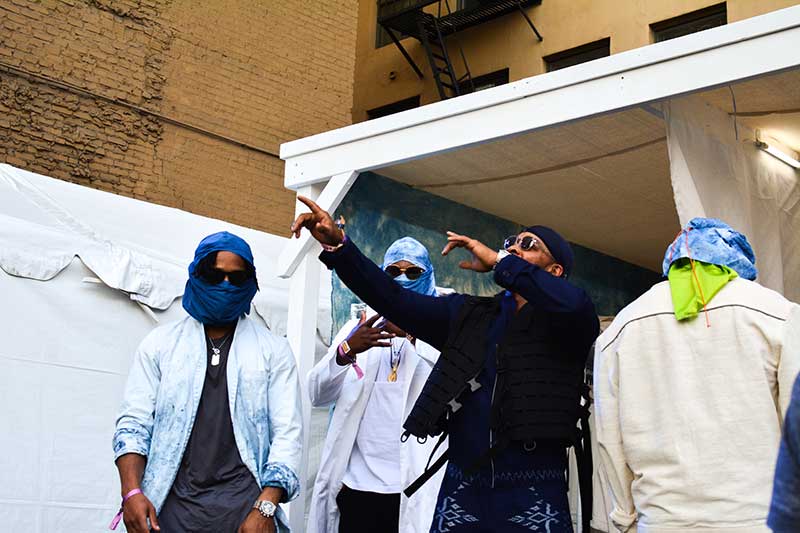

Korakrit Arunanondchai in Philip Huang

We are going to shift a bit and pick your brain! Many of us have lost work during the Covid19 pandemic and are exploring DIY projects. For people just starting or experimenting with dying, what are your favorite “starter pieces” to practice from that we can upcycle from our own wardrobe?

Old t-shirts, old napkins, and even Hawaiian shirts.

What is an easy, safe, DIY dye we can experiment or make from home?

An easy and safe dye (though it can stain your hands like crazy) is turmeric, it gives a beautiful pure yellow color, it’s not very color-fast so expect it to fade but when it’s fresh and yellow, there is nothing quite like it. Tea is another one, but I’ll leave that one till we launch our t-shirt collab with Waris to explain that one!

You also have a Survival Balm for mosquitoes and bug bites. I’ve already seen a huge increase in mosquitoes this season and more and more in the city. Many people I know have complained to me about the use of lavender in balms as they aren’t fans of the smell. What’s the key ingredient in your balm and why does it work?

The key ingredient in our balm is Ya-Nang or Tiliacora triandra leaves. The plant is common in the Isan (or Northeastern) region of Thailand and is used widely Northeastern cuisine. It is one of those miracle plants that have anti=bacterial, anti-microbial, anti-cancer, anti-toxin qualities naturally, and is said to extract poison and toxins. I think that is why it works so well. The ya nang is mixed with pandan, bergamot, and mental to bringing a cooling effect in addition to the poison extraction then mixed with organic beeswax and extra virgin coconut oil. You just rub it into the areas with mosquito bites, we find it to be highly effective.

As a holistic chef, what can we do internally to keep the mosquitoes away, or more specifically, what foods should we cut out and which ones should we increase?

Lemongrass is one of the best things to keep mosquitoes away, we use this great natural spray that is made of predominantly lemongrass that works very well. Eating lemongrass is also effective, we like it as a herbal infusion, you just boil the lemongrass, keep in a bottle in the fridge for a week or so. It’s very common in Thai cooking so that’s great. By alkalizing the body and the blood, mosquitoes seem to be deterred. Garlic is good too.

What attracts or deters mosquitoes is the balance of acidity and alkalinity in the blood seems like, so foods that make us juicer to mosquitos appear to be dairy, sweet treats, alcohol, they seem to like acidity in the blood! Or whatever it is the smells that this gives off.

Another problem during summer is inflammation and it’s becoming a more popular topic of conversation as the weather becomes hotter and cities more polluted. It can become risky treating ourselves with topicals if we don’t know how our skin will react. Can we approach this with diet and what would it look like?

In Thailand, there are so many natural and herbal remedies available, I feel like what we know is just at the tip of the iceberg. There are cooling foods and heating foods, in the summer, to avoid inflammation it is important to have cooling foods, but you don’t want to overdo this either, it is about keeping a balance. Turmeric in the heat would heat up the system, this could cause inflammation, the counterbalance that with something cooling like coconut water. What we’ve learnt from being here is that the idea that food is medicine is very much a part of life here. If you look at a papaya salad, what is so common in the Northeast of Thailand you will see a balance of cooling and heating with a good hit of chilies and lime, these can function as anti-oxidants. The more we get into plant dyes and the power of plants the more we realize how important it is to include these miracle plants in our diet and how things like sugar and yeast must be eaten in moderation. Take the indigo vat, it is a living breathing thing so it needs the right balance of acidity and alkalinity, also the right quantity of food and air, too much sugar from fruit or too much lime will throw it off. It’s like our own bodies.

Talking about food, how did you participate at the Summit DTLA with Ghetto Gastro? And can you please tell people what it is?

In 2018 we were invited to take part in SUMMIT DTLA, SUMMIT is this really ambitious gathering of people with collaborators and guests across many industries, we were invited to do an indigo experience at the 2018 rendition in DTLA, and we were really happy to see our friends Ghetto Gastro there too. Ghetto Gastro were invited to create a food experience/dinner one night during the 3-night extravaganza. It was totally epic. SUMMIT attempts to engage and question the status quo by bringing people together. I feel like Ghetto Gastro do this all the time, daily, at SUMMIT was just one example, using food as a tool, recently more as a weapon to highlight the flaws of history, the narrative, and what we can do to make things better. Food is what unites everyone.

Finally, with those of us losing hope and especially hope in the industry, what words of encouragement do you have?

There is always hope if you believe that there is an alternative. There is more than just one vision of what things should be, we must not be afraid to venture out and search elsewhere knowing that there is another way somewhere else. And believe that once you embark upon that journey there are like-minded people that will and take that journey with you.