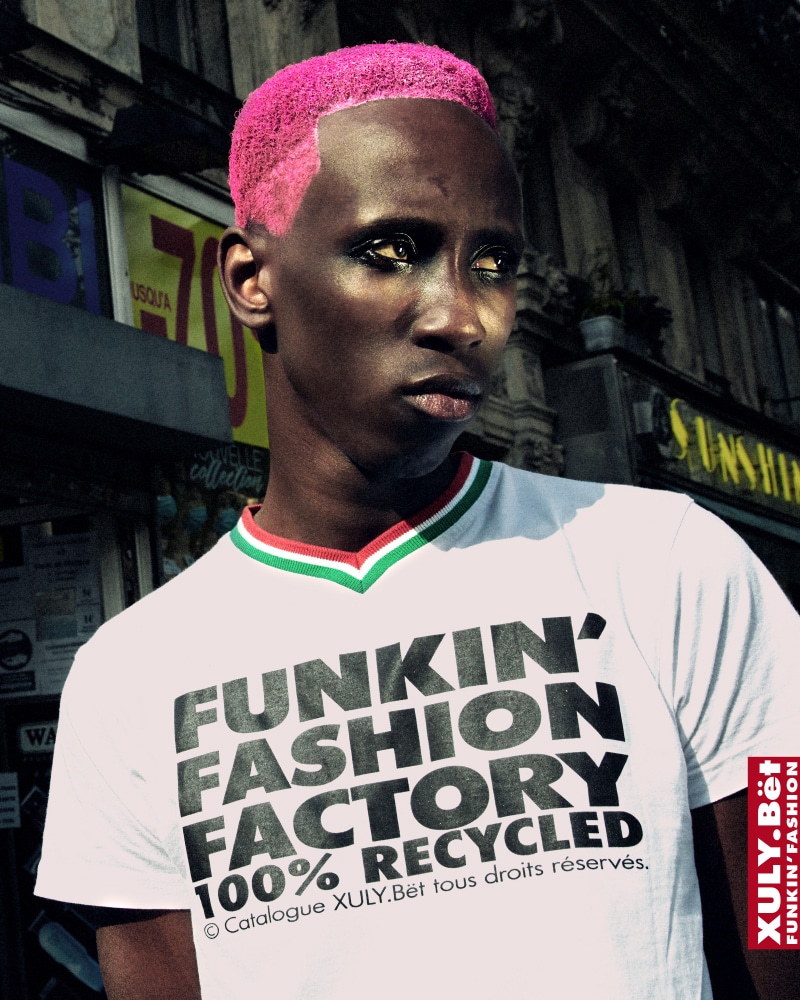

First of all, XULY.Bët is not a person. It means means “keep your eyes open” in wolof. The designer behind the cult label, and what feels like sometimes the best kept Parisian secret, is Lamine Kouyaté. Today we are experiencing a much-anticipated wave of designers from the African diaspora, but they are just making headlines in recent years. Since the early 90s, Kouyaté was something of a futurist, exploring upcycling, and suburban youth in the luxury world of fashion, and breaking down many of the rules making way for the talent we see today. Fashion cinephiles also know his pieces (and perhaps his personality too) from playing a prominent role in Robert Altman’s film Ready To Wear (1994).

What still sets this Mali native apart in my eyes, is that he never quit designing for the youth that inspires him and making sure that his creations are affordable and most of all wearable! After more than twenty years, we are finally seeing conscious fashion make its way from cult to cornerstone.

When I first moved to Paris to study fashion in the late 90s, I really wanted to intern for you! Every year there are new fashion graduates and while I get older, they stay the same age. So for all of those fucking young ones out there, we need to start back in the 90s. I feel like I first discovered upcycling through your work, it wasn’t a trend or movement back then. What inspired you to do it, how did you approach it and what were the initial reactions from the luxury fashion insiders?

I actually tried to pick up fashion with a wide spectrum of things that I could tap into. I also had an industrial vision, of course, but I wanted to do something for the suburbs so with a more accessible approach but also to translate things that they wanted to see and express (the insiders). Broadening the material spectrum has made me break out of preconceived ideas and things that already have a life and that can be more easily brought back into the everyday locker room. For me, it was also a school – a whole time like scratchers in early hip-hop who took broken records and made new ones.

We all started with things we already had on hand and lived experiences. It had to be a collective vision that didn’t just come from me. On my part, these are things that I have experienced that have animated, nourished, and educated me. In Africa nothing is thrown away – every coin has a value. It is this cultural heritage that allows you to keep a certain openness.

Many of us have spent our Covid19 lockdown trying to upcycle at home. I have lots of asymmetric tops and sweater vests now. Are there any specific tips you have for us?

You have to find the style you want to wear! You have to look for what you can find on the side, to upcycling you don’t have to go far! You don’t have to go to New York to find something to recycle, already in your own closet! You have to look nearby, the pieces of your older brothers or your parents that you can bring back to the sauce of the day. Today, time is running out in tailoring. Before we took longer to work on a shirt than today, there is a quality that there was in the old shirts that cannot be found in the current pieces – they took the time to find the right ones. Good materials, when you bought a shirt it was for life!

Back in June, I saw many articles that focused on black fashion designers, it was great to see so many pieces, but I kept seeing many of the same names and not yours. As part of the industry, it seems very late to only start discussing inclusion now. How did you find the industry when you first started and why weren’t you shy to dive into your African roots? Do you feel that things have changed?

I had a vision as a designer, I drew from my roots without hesitation. I was not very demanding, when you see things with your heart and with discernment, you can tap into everything. Whether in upcycling or in ancestral cultures like in Mali where there is a prolific textile culture that had to be brought up to date to modernize it. We had to get out of the dogmatism of fashion.

“The tiger is not going to proclaim its tigerness”, it arrives and leaps! I didn’t have to rock it and claim my skin color, it was very natural. When you look back, there are still inertias that mean that when you are black you do not have the same access to the market. We are victims of this system, that I can say. I came with my ideas, my know-how and I gleaned an audience.

Designers today are known for their street collaborations as much as their runway collections. You were the first designer to do a high fashion-sportswear collaboration (Puma), did you see something in the future or in the streets that the rest of us didn’t see at the time?

Already in the subjects – I immediately took advantage of the technical subjects which were immediately a field of experimentation. All sports materials, lingerie, and comfort. I thought there was something to look at in the women’s locker room in relation to sport – there was an endless void there.

What interested me in sport was to realize women because there was nothing for them except the chic and bourgeois side!

Funny how something so basic as mobilization is dramatically changed with a pair of trainers! For many years, you were described as an “underground” designer. Was that by choice or circumstances?

The circumstance had something to do with it. “Underground” is kind of benching, whenever you come up with something that might bother you. But I was still more popular, we sold XULY.Bët in small shops in France, the market was quite large. The structures were so sclerotic that we were quickly on the sidelines – I was speaking more to the young people who were just emerging.

Multiculturalism has always been a part of your brand DNA. Where do you draw the lines between cultural appropriation and multiculturalism in today’s fashionscape?

I think you have to get out of the mind-frame of “culturalism” in order to approach it. Culture is not set in stone. When you come into culturalism it’s like slipping into a straitjacket. When we talk about multiculturalism today, it is negative. I see it as symbiosis – humanity has always functioned by taking from neighbors. Otherwise, we don’t move forward. Culture is the most distributed thing in the world. Everyone is moving in this direction, there is collusion.

You have dressed Gen X, Millennials and now Gen Z. What is it about designing for the youth that inspires you, and how do you feel the energy of Gen Z?

I think today we are coming to a point where a lot of questions come up as obvious. The problem for young people with regard to the future creates an anxiety that is even stronger today, we have all experienced it but it is still different now. We must try to give them a more collective and positive option on living together. Surely this is what they find in what I do, these are questions that I tackle, they find themselves in this.

You decided to have a physical show for your SS21 collection on the edge of Paris with DJ Honey Dijon doing the soundtrack. Why was that important for you?

We discovered that Honey really liked the brand, we wanted to work exclusively with women on music. We started with a concept based on affinity. We wanted to talk about femininity and she embodies that femininity, being transgender she radiates even more energy than anyone. She embodies what we wanted to express.

I really like her own line of t-shirts as well! Focusing on femininity is an interesting time in recent history as toxic-masculinity still rampages on. Can you tell us about your SS21 collection and more specifically about the direction of menswear?

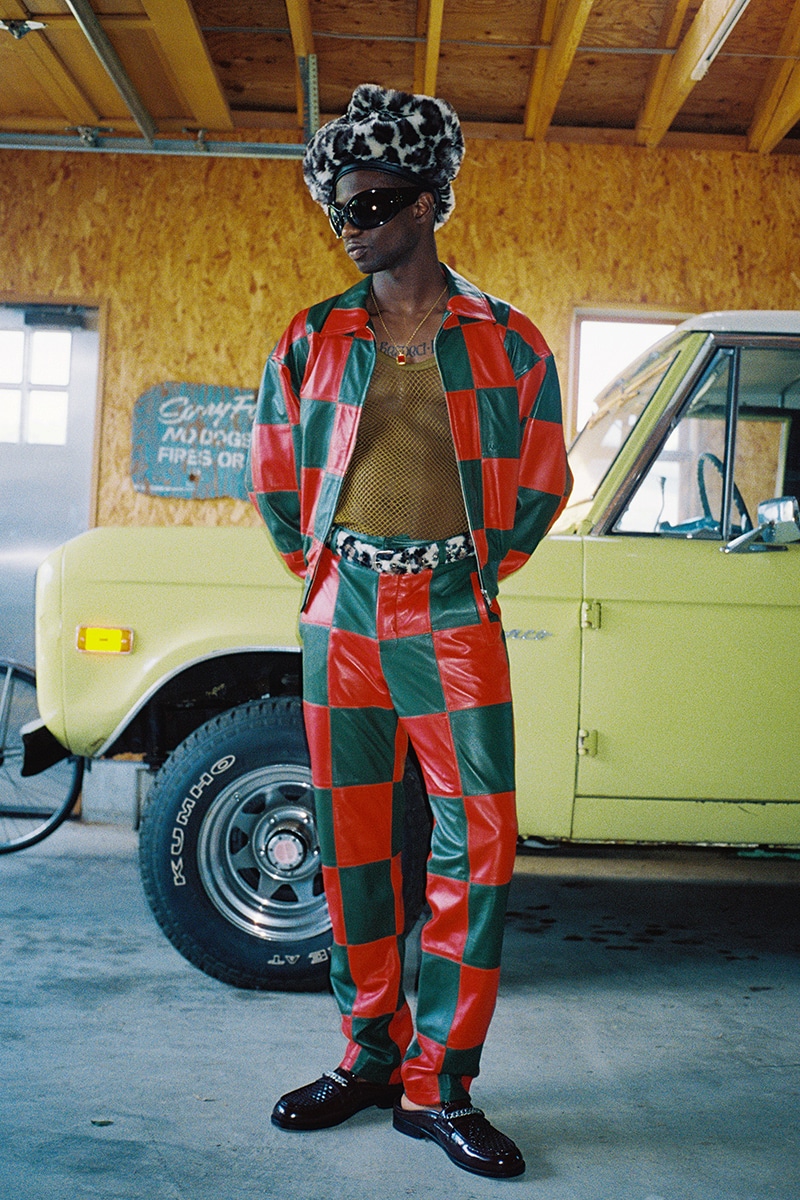

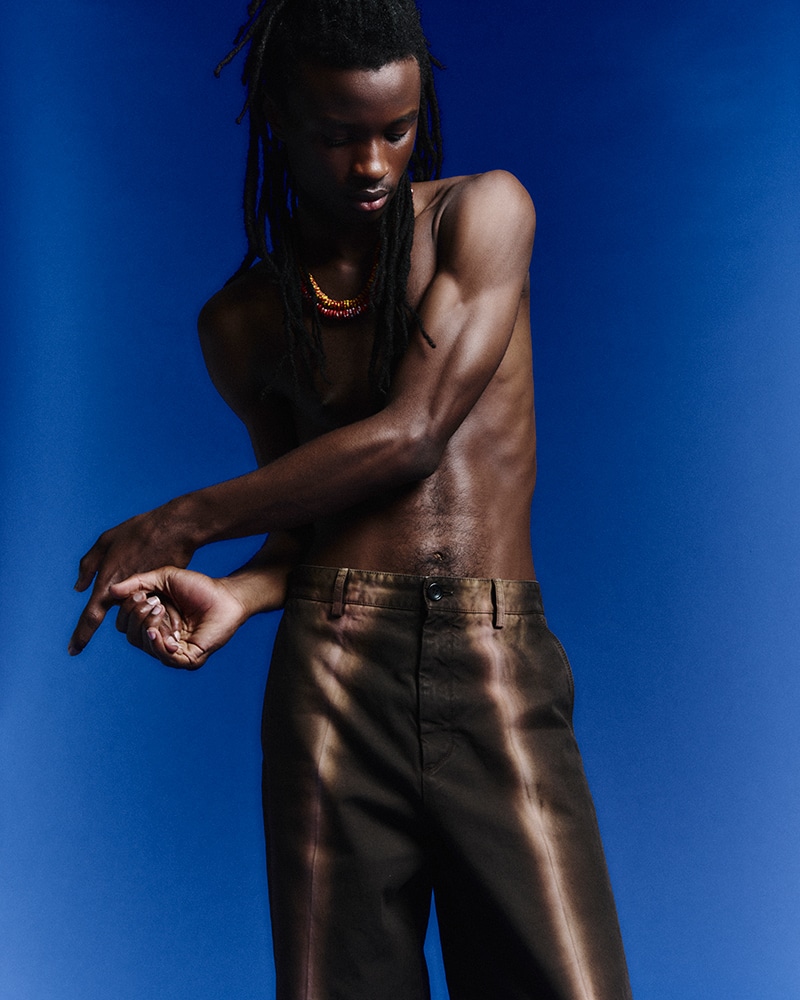

In this collection, the man/woman fringe is ambiguous, which is what creates a space where you can take in both women and men. It’s a package like a cocktail that you craft with enough ingredients to be gender-friendly. For the two together, separately, there is an equilibrium and synergy in the clothes of this collection.

You are by far not fast fashion, but your price points are much more affordable than luxury. This is incredible with so many pieces being upcycled it is in many ways one-offs. How do you manage your price points?

We already have a bias, we don’t want to make clothes just for people who have money. The level of luxury shouldn’t be a barrier – I’m more on the envy than the means. To be in our reality it has to be affordable. I prefer clients who keep their money to travel, live, and have fun rather than being in consumerism and ruining themselves by buying a dress for 1400€!

I couldn’t agree with you more, and whenever anyone has asked me for advice, I always say travel! Before we disconnect, in general, what are you optimistic about?

Awareness! More and more space for freedom and mindfulness is granted. It makes me optimistic!