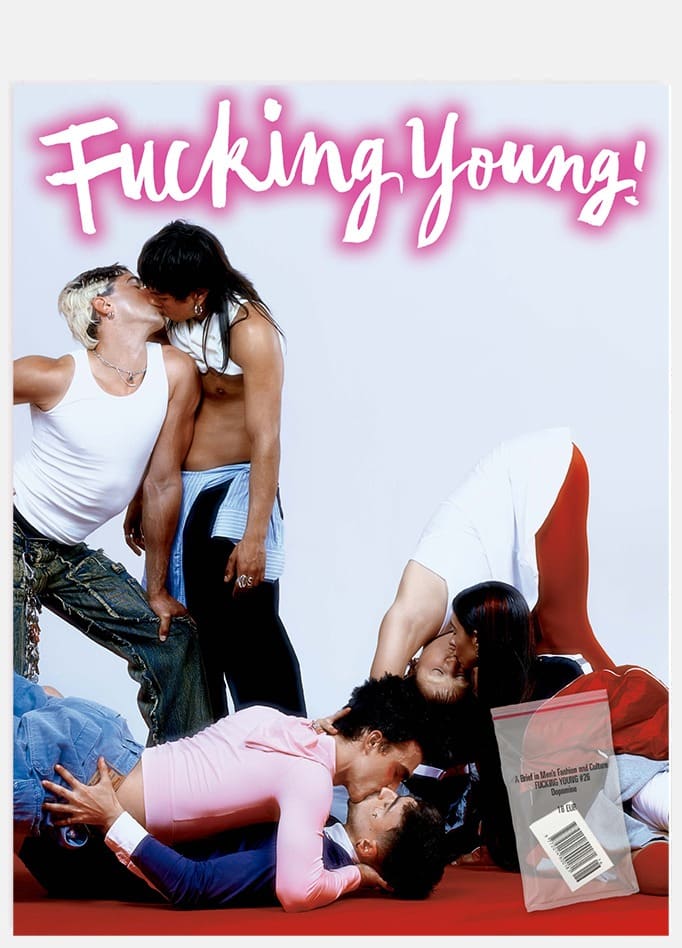

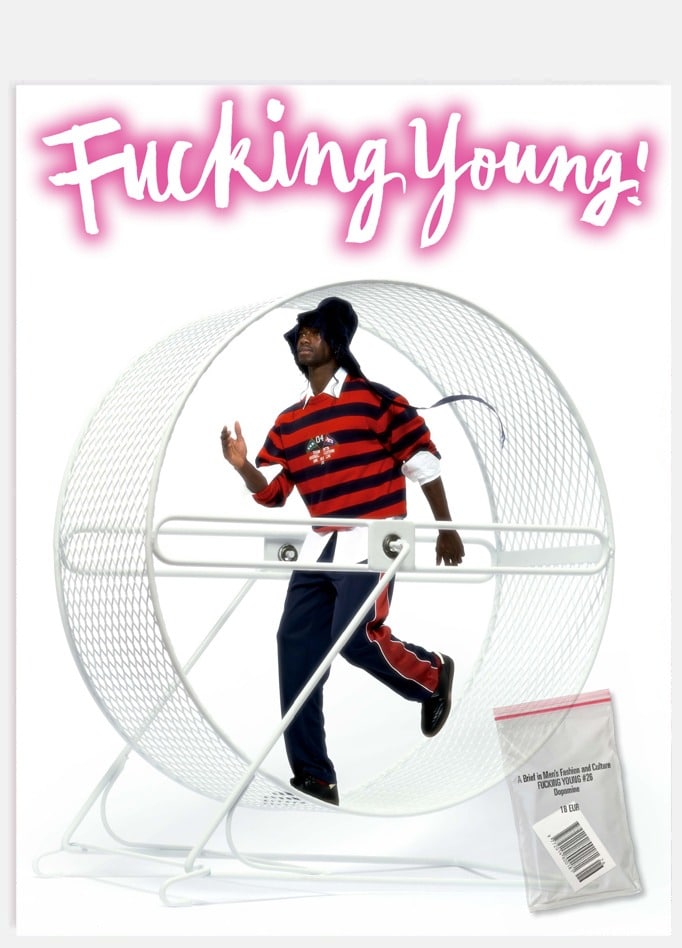

This interview was published on our “MENA” issue. Get your digital or print copy HERE!

Omar Braika and Shukri Lawrence are unapologetic about making political statements as fashion statements, using tRASHY Clothing to challenge preconceptions about the Middle East. Collections and campaigns play on stereotypes to highlight discriminatory views that are what is considered different, cheap, and trashy in modern culture while highlighting Middle East subcultures.

In a world where fashion can take itself way too seriously, there is a spirit of anti-fashion to tRASHY Clothing that catches you by surprise. Transcending borders, race, or gender, and the young offer pieces that speak of Arab and Palestinian identity as it breaks down the stigma attached to the language and culture. But never have I seen a brand that looks so much fun and free in the process, making waves for a new generation of creative minds.

tRASHY Clothing is made up of Omar Braika and Shukri Lawrence. How did the two of you meet and what drew you to create the label?

Shukri: I was born and raised in Jerusalem and came to Jordan to study film. We both met online, on Instagram, Omar was doing documentary work in the Zaatari camp in Jordan. We started to talk about our work and what we wanted to do. We saw a lot of misrepresentation in fashion which pushed us to work on projects together. We first started with making t-shirts before designing Ready-to-Wear.

Would you say that photography is the heart of the brand?

Omar: Photography and film, both.

At what point did you decide to expand that vision to fashion?

Shukri: Growing up we were always into fashion and knew at some point we would end up in the industry. The first inspiration for the brand was bootleg; anti-luxury vs luxury and the cycle of influence among classism. We began with releasing T-Shirt drops to introduce the brand and then expanded the vision through designing fully Ready-to-Wear.

Omar: We also don’t have representation in fashion. At the same time, looking at many brands, they are taking inspiration from the MENA region, but it’s never mentioned or credited. We felt we should fill this space.

You mentioned classism and knock-offs, do you feel that there’s this stereotype in fashion that the Arab world looks cheap?

Shukri: That’s a stereotype we try to tackle. In our last resort ‘21 collection, we imagined a belly dancer that is more luxurious than life with metal mesh and handprinted pieces. We wanted to break down the satire or debunk it, the excess, saying “I’m basically more luxurious than you will ever be, I’m modeling for this brand Trashy Clothing.”

Omar: Belly dancers are still looked down upon and seen as cheap. Who gets to decide what is tasteless and what is tasteful? The fashion industry could be toxic from the way they shoot the model to how they treat them, it feels like it’s just one person who decides what is fashion and what is not.

And it’s usually a Western person who decides. Going back to classism, your casting whether in campaigns or lookbooks looks more like the world we live in. When we look at the runway in Paris, Milan, and London, it still isn’t nearly enough inclusivity to reflect the people that make up the city, notably a lack of Arab models. I’ve noticed this even when contacting agencies. Why do you think that is? Do you think luxury brands just want a “certain” type of person to be reflected in their universe?

Shukri: The idea of diversity in fashion is being treated as a trend. Whether it’s an Arab or Asian model, it feels like they’re being sprinkled in, it’s not authentic, that’s why are don’t have many Arab names of models in the industry or walking shows. You can just count them on your hand. We live in a world of virtue signaling, we need authentic representation and diversity.

Omar: Even in fashion, if a new trend emerges, there’s a label for it. Like streetwear, they give it a label because they don’t think it fits the fashion world. That way, it can just come and go.

Talking about labels, I’m going to throw “utilitarian” at you. Looking at your use of layers and undressing, is there a certain utilitarian element to your design approach? Even if we don’t see it on our first impression.

Shukri: I think the reason why it has that approach is that it’s inspired by storytelling, we use metaphors in the zippers. For example, in our Spring Summer ’21 collection, we were inspired by undressing, quick changes, wraps, and draping. It was really about our experiences at checkpoints, going from Palestine in and out of West Bank in Jerusalem. A sad reality growing up, my family would undress like taking off a jacket to look more “western”, so we could pass easily and not get asked more questions. The idea of undressing and looking more western helps you to get home faster, it’s crazy. Even if we are listening to music, we need to switch it from Arabic to any other language. How do we tell that? So we imagined zippers.

Omar: It also shows that we don’t have control of our bodies. So with the designs, we are choosing what we want to show, reclaiming control on our bodies.

When you talk about the checkpoints, it’s like a double identity. On the subject of identity, the label doesn’t hide being queer or queer-friendly. How can you be openly queer with your label where you are based?

Shukri: I think it’s so needed for a label to be based here and be unapologetically queer, to be a home for other queer Arabs, Sharing our admiration and inspirations we all have from Arab pop stars to queer icons. It gives homage, a sense of hope, and representation. We get a lot of messages from people who feel connected to what we are saying and relate to it. The thing about being open with identities is really about privilege. If someone has the privilege to be open, it’s important to use that privilege to benefit those who aren’t able to.

Omar: Straight people don’t have to “come out”. The idea of coming out feels like there is something wrong with me, but it’s like no, this is who I am. No one wants to tell their parents who they sleep with.

With your brand and being openly gay, how do you reach the Arab market? How has the reaction been?

Shukri: The response in the Arab market has been great. There’s a need for representation, especially in fashion. Having a label that brings cultural & political motifs into everyday pieces is needed in the Middle East.

Omar: Trashy Clothing also created an online community, a year ago we created a page on Instagram called @trashy_files where we would share our inspirations, moodboards, and archives from Arab pop culture; the page grew to the point where people are now submitting iconic moments themselves. We are sharing all of these together and at the same time, it is inspiring our designs and conceptualizing our collections through these references & archives.

You make references to many Arab divas, icons, that clearly inspire you, who are some that we should know? Like who is the Mariah or Britney in the Arab world?

Shukri: Haifa Wehbe, Nawal AlZoughbi, and Ruby, I guess you could say are the “gayest”! If you play their music at a party, everyone goes wild.

Do you feel that anyone could wear your clothes or for me as an example, I’m a cis white American woman, would I be called out on cultural appropriation?

Shukri: Not at all, the clothing we make is for anyone who feels connected to it. It’s not traditional clothing but it is inspired by culture. If you feel connected to the brand’s message that’s what matters.

Going back to the subjects of metaphors, fashion is a language that doesn’t use words. What can clothes tell about a person?

Shukri: Expressing yourself is so important. Each of our collections has a theme and each piece is part of that story. From inspiring pop icons to the checkpoint experiences. The idea of claiming your sexuality back to the idea of reclaiming your body. We also like debunking the myths and stereotypes put upon Palestinians. We also want to show that Palestinian Christians & Jews exist alongside Palestinian Muslims.

I’m also half Armenian. Palestinian Armenians are also part of Palestinian society. They have their own quarter, in the old city of Jerusalem. Some of the prints in our SS21 collection are inspired by Armenian ceramics. We want to honor the Armenian Palestinians that are living in Palestine and debunk the pink-washing. The spring collection was basically about pink-washing and what it is like being a queer Palestinian.

The media makes it sound like we don’t exist or are beheaded the moment we step out the door, it’s basically crazy fake news. That was the idea behind the campaign for our SS21 collection which looked like a tourism ad next to a pool. At first glance, it looks like a normal summer fashion brand campaign, but when you look deeper, you will see one of the models has a handcuff, while another one is getting arrested on the side, and there are two Molotov bottles on ice. We wanted to get rid of the pink-washing and present a fabricated “gay heaven” in the campaign and show how Tel Aviv is not really the gay heaven it presents to be, it’s not real, and there’s discrimination against queer people whether they are Palestinian or not. Even if the person is queer, they see every Palestinian the same.

Omar: They are using human rights and gay rights to promote themselves. There’s a song by an Armenian Lebanese singer called Maria where she asks “why are you lying to me?” and in a sarcastic way for our SS21 “Pride for Pay” drop, we put her avatar in the desert next to the sea with a helicopter spying on her as a teaser for the collection.

Shukri was born and raised in Palestine and has talked about facing the checkpoints. Omar, can you tell us a bit about your roots.

Omar: I’m a Palestinian refugee, and grew up here in Jordan. I am actually unable to travel to Palestine. Palestinian refugees aren’t talked about enough when it comes to Palestine, as if we don’t exist. Talking about it is like talking about how the occupation came to be. These are the things we try to mention in our collections using numbers or words sometimes.

Shukri: Last Autumn Winter ‘20 we did a tattooed-inspired piece that had all of the identities on it. Like the number that really represents the refugee is the year 1948 when Palestinians were expelled from their houses.

Omar: Tattoos were a really big part of our culture. Women used to tattoo their faces always with significance. Some do it themselves stick and poke. That shirt was really about tattoos in the Arab world and the different ways it is done. Clothing is the skin we want to wear.

For many of us, fashion has been a natural escape since we were children, would you say that’s true?

Shukri: I used to watch Fashion TV growing up, I didn’t know who the designers were or what was happening but I very much tuned in. It was an instant escape and I couldn’t stop watching.

Omar: For me, I didn’t really know names or how fashion worked, but as a kid, I made clothing from leftover fabric from the tailor where my mom worked for my sister’s dolls and I was sketching. Growing up I used to style my family. My grandmother was surprised when I studied media and not fashion.

But now you have a brand! Where can we find your atelier and what is a typical day?

Shukri: We just relocated our atelier here in Jordan. All of our tailors and patternmakers are local and we produce per order. You’ll usually find us playing a playlist inspired by one of our collections as we work on our orders or design upcoming seasons. We try to eliminate as much waste as possible including reusing fabrics for future seasons and upcycling so we’re always experimenting on our mannequins.

Omar: We want to help our community and working with locals helps from fabrics, models, to makeup artists, we do good when they do good. We don’t really make anything outside of our community, we are creating our own cycle. Our Fall Winter 2021 runway show is shown in between Iceland and Jordan, so we’re bringing everything local to Iceland too!

Moving onto fall, can you tell us about your Fall Winter 21/22 Collection? And Iceland, why, how?

Shukri: The AW21 collection has been in the works for almost three years due to the pandemic. It was supposed to be showcased in March 2020 in Iceland, but when we were about to leave and had our bags ready our flights were canceled so we had to postpone. But now, the collection is here.

The collection is called Errorvision and is inspired by song contests, sports competitions, beauty pageants, and the massive politics behind these events. Like when you say something is not political, but then use flags, it’s super political, it’s a presidential race! So with this collection, we are presenting a ‘presidential race’ within these contests. We’re also asking: Why are soldiers joining song contests, to art-wash their government’s crimes? The other side of the collection is focusing on the idea of protests, boycotting, using your voice. The right of resisting those who occupy art for governmental financial gain.

In 2019 we collaborated with the Icelandic Eurovision contestant Hatari, they are a BDSM, electronic, heavy metal band that raised the Palestinian flag during the Eurovision in Tel Aviv, so we wanted to collaborate with them again in Iceland and have them be part of the show. Wherever we go, we want to bring Jordan and Palestine with us.

Omar: And how technology is helping to control us. Like algorithms, for example, if you use certain terms like Palestine in the past few months your engagement would go a bit lower because you get shadowed banned without you knowing unless you point a random selfie to make your engagement go back up again.

Shukri: A few months during the events in Palestine, a lot of activists were posting the news and in between posting random stories of like a cat with #cat to help beat the algorithm and would censor the words in a way to pass. So for example, if we don’t use the points in Arabic, it can’t read the word. It is a lot about playing with AI and what the robots can’t control.

Earlier you mentioned the word boycott, do you think boycotts work?

Shukri: Boycotts definitely work. If you are going to add pressure on anyone’s wallets, they will listen. It’s a peaceful way to be heard.

You recently did a ‘FREE PALESTINE’ t-shirt collab with Berlin-based brand GMBH. How did this collab begin?

Shukri: We have been following each other and wanted to work on a t-shirt where proceeds could be donated to a charity and using the piece as part of their SS22 collection. We talked about how it could look, shared our sketches and archive.

Omar: It happened very quickly as they were preparing for their SS22 runway show and we wanted to make a statement. We have similar backgrounds, Serhat is from Turkey and Benjamin from Pakistan, both want to put their identities into the brand and push that into fashion. That is something we bonded over.

Can you tell us about the charities that the collab’s proceeds will be going to?

Shukri: The first charity is AlQaws, an LGBTQ+ Palestinian organization that supports Queer and Trans Palestinians in Palestine either financially or psychologically and they also host events, queer parties, and drag shows in Palestine. The other charity is The Land of Canaan Foundation that supports farm communities and village-based cooperatives in Palestine.

Has the Trans community in Palestine received moral support from the LGBTQ community from around the world? It’s something that we never hear of.

Shukri: That’s the thing, they will say something like a Queer or Trans person will die in Palestine, its this idea of attacking a certain identity just because they’re Palestinian. It is transphobic and homophobic. There is a Trans community in Palestine and their experience really depends on their background and their community as well. Some of them have the chance to live within the community, be accepted, and live with their identity. Others, like anywhere in the world, might not have that privilege, so they have to flee or find a safe shelter.

As queer/trans-Palestinians we have two struggles, the struggle of queer/trans liberation and Palestinian liberation.

In order to have both, we need to have Palestine liberated so we can have our rights because you can’t really think about anything other than to eat or sleep or survive if you are living under occupation. Everything is basically controlling you. It’s a privilege to be able to not think about these things. Palestinians living in Jerusalem aren’t living the same life as someone in Gaza for example; there are all different situations. Passing in Jerusalem there are soldiers all around, always checking with cameras, you are always being watched. I have to use my Armenian identity, not Arabic when speaking to soldiers in Jerusalem to be able to ease interactions with them. When confronted with fear, you have to have a safety shield. They do not care if I’m queer or not, as long as I’m Palestinian I am a target for abuse.

In addition to Palestinian and Syrian refugees, there are LGBTQ refugees from around the world, and now we have been witnessing the sad chaotic situation in Afghanistan. Refugees are invisible here, meaning we like to pretend that we don’t see them or acknowledge their story. What do you think the West gets wrong about refugees?

Shukri: The reason that refugees exist is from the governments of the West. When you go into countries and destabilize them, the refugees will come. The Taliban for example was founded by America.

To beat the Soviets in the Cold War, and they told us not to go.

Shukri: Refugees are looking for safe shelter due to the troubles of Western countries interfering.

America likes to build things in its image. If you were to build things in your image as you do with the brand, how would it look?

Shukri: When designing we always look at the past and the future.

Omar: We start at zero and ask, what is we are seeing happening now. Like why are the four fashion capitals the only four? Why isn’t every capital its own fashion capital?

Shukri: Yes, what if there was no structure like that, how would fashion be different. How many Arab names and brands would we have for example.

Omar: In the Middle East, the laws against the LGBTQ community are from the colonizers. Before the concept of wearing eyeliner or a dress wasn’t associated with gender. Arab men have long hair and wear dresses, like robes, and wear mascara to help protect their eyes from the sun. The occupation told us what to wear and what not to wear, how to eat, talk, everything. So their views were normalized.

Shukri: Even here speaking a European language elevates your class. One of the reasons we called the brand Trashy Clothing is because lots of shops around the old city always have names like “Elegant Lady” or “Fashion Extravaganza”. It’s a play on the fantasy of luxury by asking who gets to decide what luxury or good taste is.

Before we disconnect, what does it mean to you to be fucking young today in Jordan?

Shukri: For me, it’s about being able to work with the people that have always inspired me. Achieving what my teenage self always daydreamed of, while being based in between Jordan and Palestine. Bringing my dreams home.

Omar: I want the next generations to have fewer traumas and a space to represent themselves in. We miss a voice of representation in fashion. To be able to see myself in fashion is what my younger self would have wanted, and I’m working on bringing that voice now.