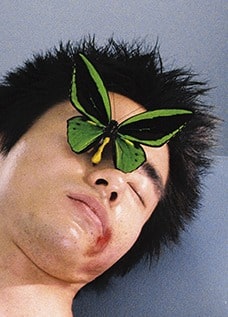

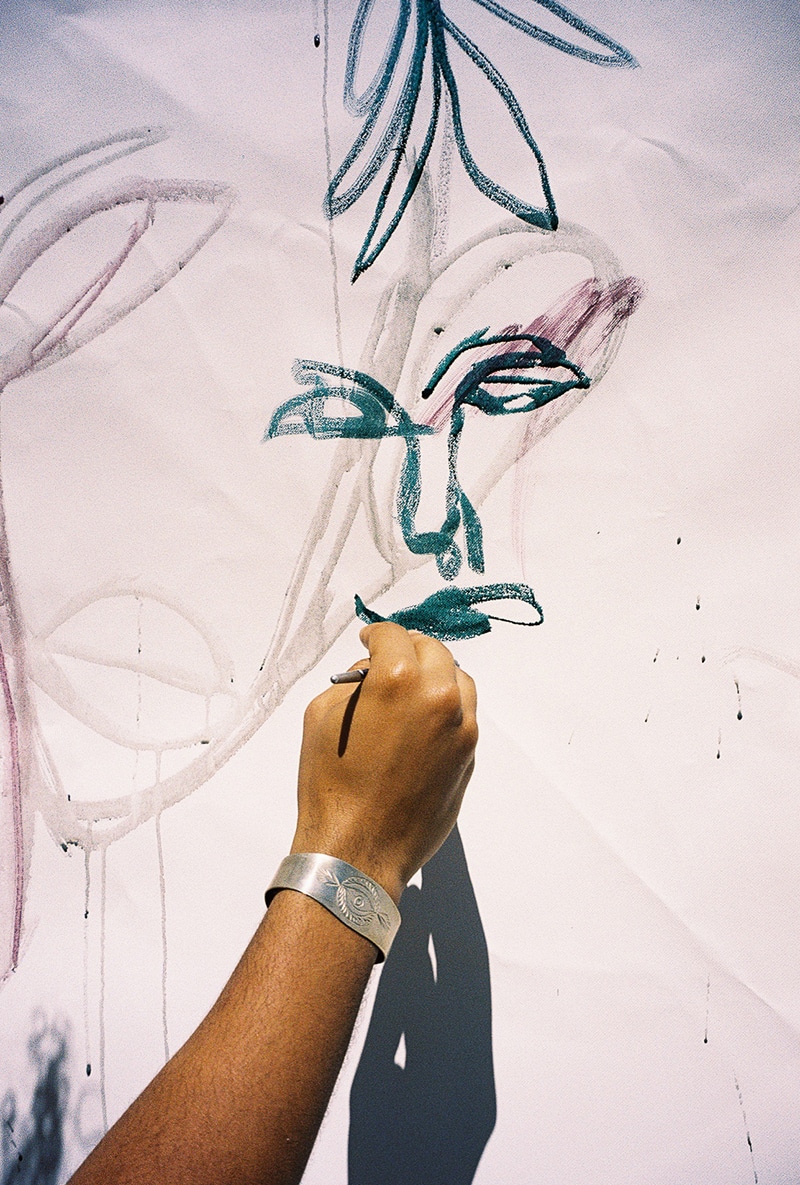

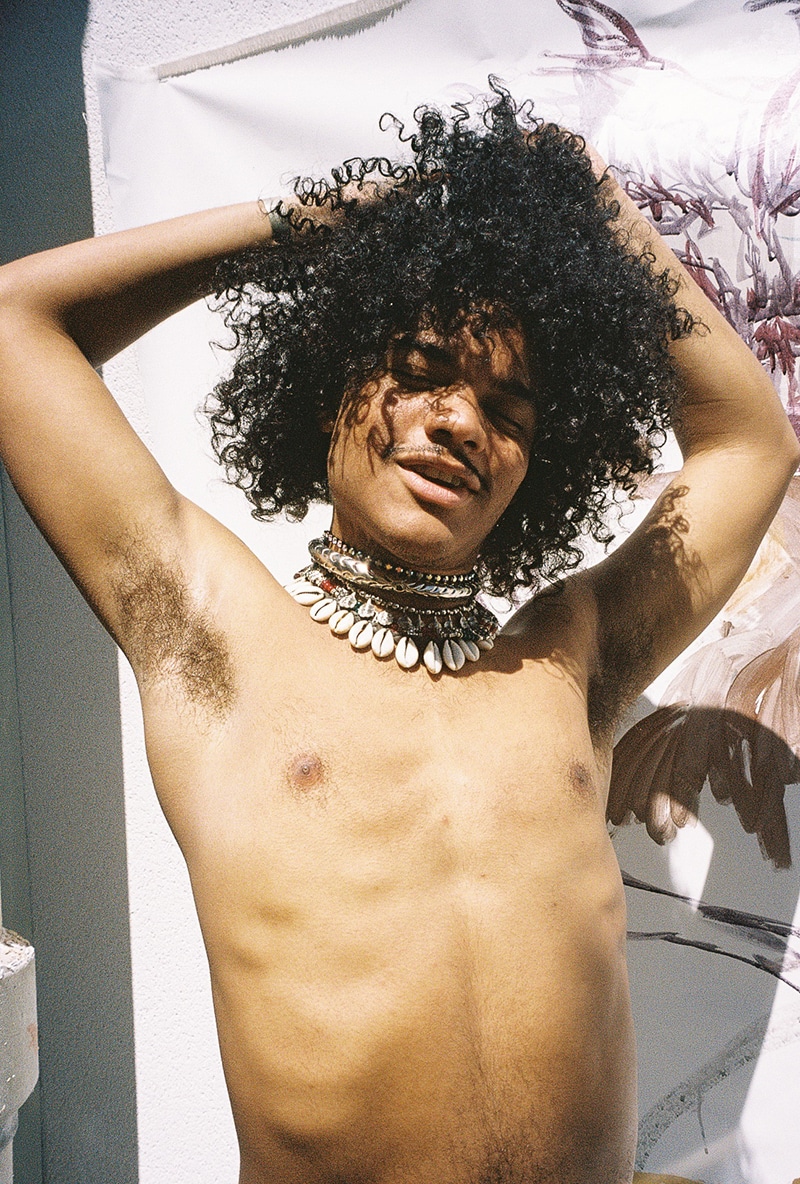

What’s it like to be black, queer, and a resident of one of Brazil’s infamous favelas? Samuel de Saboia, 21, answers these questions through his art. A native of Northeast Brazil’s Recife, the pastor’s son has been dubbed “the next Basquiat” by Brazilian media, nabbed the April cover of Harper’s Bazaar Art Brasil, and flexes his personal style muscle on the ‘gram when not posting #newwork. His 2018 exhibition in New York was met with positive feedback, which led to Samuel’s most recent residency in Paris. I spoke with the contemporary art scene’s it-boy about what life in the favela is actually like, the black queer experience in Brazil, plus his take on fashion versus art.

As someone who is part of two marginalized groups, how would you describe the black queer experience in Brazil?

It’s a utopia of its own, that feels like this tangled web of dreams and reality. It’s almost as if we pretend like everything is fine when we are together as a community, but then on our way home, we all fear for our lives – calling each other, seeing if everyone got back in one piece. We fight hard for our loved ones and consider each other family since many were kicked out of their homes at a young age. It’s very much about support and inclusivity, but we’re in need of more safe spaces.

What would you say are the biggest misconceptions that exist around life in the favela?

The ways in which people who never lived in one tend to view it. There’s so much love, happiness, and creativity in these areas. Especially when it comes to people’s living conditions – they’ll create the most with the bare minimum. This fuels one’s creative ability and I often think that if I could make it when I had nothing, I’m more than able to do so now. The whole violence issue is a separate topic. Especially in places like Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and my hometown Recife, situations of extreme violence involving police militias – which often take advantage of poor residents to turn a profit – are not uncommon.

You’ve been compared to the late Jean-Michel Basquiat by Brazilian media. What are your main differences and similarities as artists?

When it comes to new artists, as a black body the media feel more comfortable delimiting you via the use of a label. It allows them to build and predict the narrative. Similar to the late Basquiat, I go against the wave – I not only discuss and ask questions, but also bring the responses. Innocence is also a trait we have in common, even if mine is well-hidden but always present. When it comes to the strength used in the brush, I tend to lose myself and find myself again in each new painting. Throughout the process, I can feel either extremely vulnerable or like a beast. It’s good to have some resemblances, but I’m building my own legacy and thank God that I’m able to get further with my own vision.

Could you share the story behind your work that discusses the hate crime against your transgender friend?

There are two works that I made thinking of her. The first is Lambança e Curtição, which means “licking and partying” – it discusses the dance of death and how painful it is. The other work is As Lavadeiras, inspired by her and my late godmother. She was one of my best friends, a sister, and a healer. We used to talk about the sun and how our skin holds all that energy. She studied art and danced to the beat of her own drum. Days before she was murdered we did a performance at the biggest Latin American art fair, talking about the extermination of black and queer bodies. A few days thereafter she was beaten to death and her remains were burned. In As Lavadeiras I celebrate her kindness and the way in which her words healed others.

What’s your take on the “fashion is art” notion?

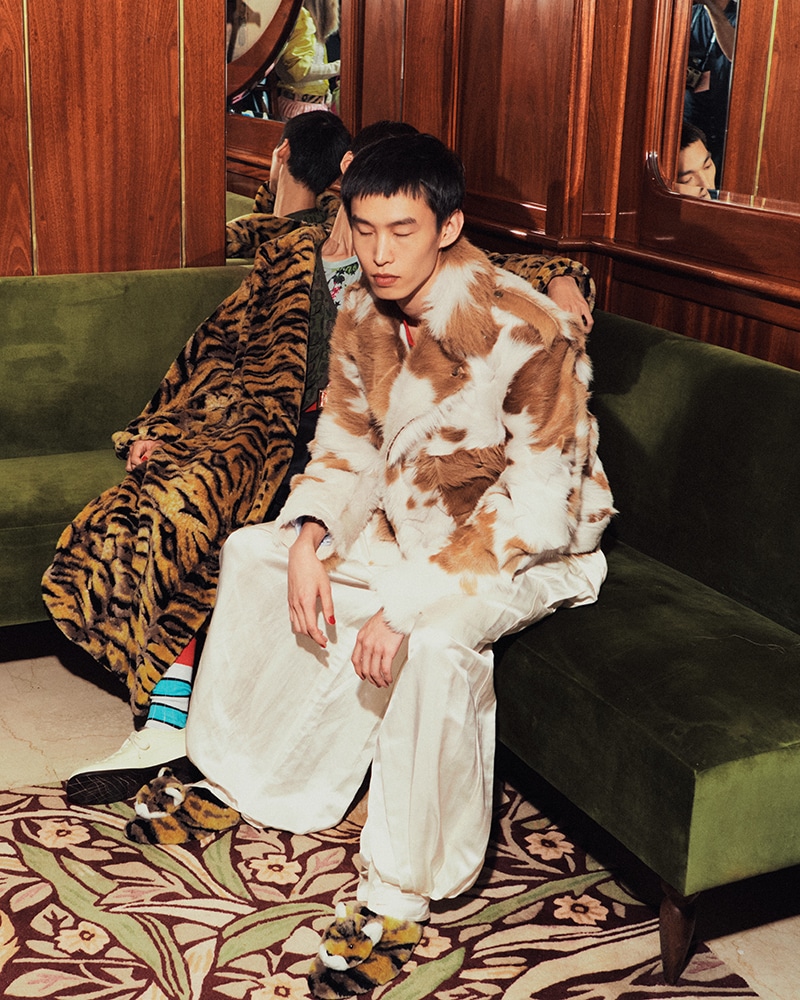

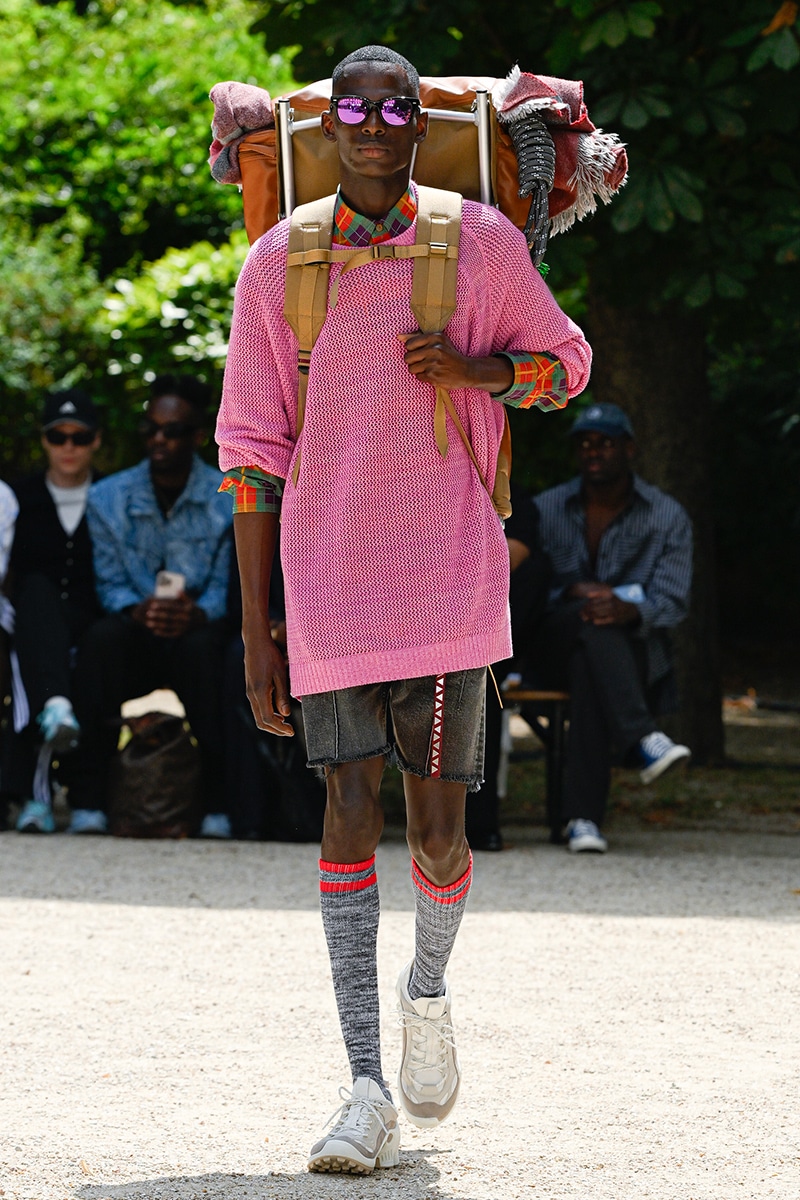

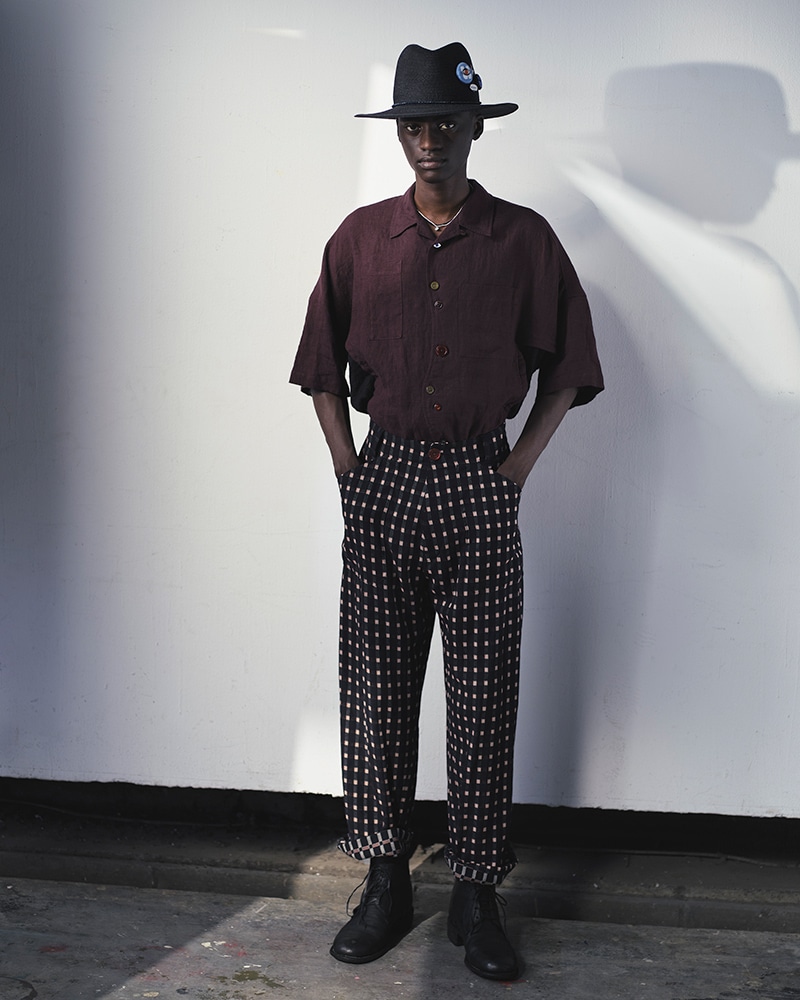

Fashion can be art, but not all fashion is art. I appreciate both the same way since both genres produce so many works that make my heart melt. The whole “designer x” hype has a huge impact on consumerism but also blinds people from recognizing true craftsmanship. When it comes to fashion, I care not only for the piece, but the entire experience. I see clothes as a memento – there’s an element of nostalgia to them. Seeing my rotten Comme des Garçons shirt, makes me remember how I was kissed while wearing it.

Paris or Recife?

Both. I wouldn’t be in Paris if I hadn’t gone through what I’ve been through in Recife. My hometown pretty much shaped me as the person that I am today. Each second on the beach; walking butt naked in flip flops; climbing trees; diving in the sea; getting drunk with friends; making crowded queer parties and drinking cheap booze, prepared me for fancy dinners; gala parties; fashion shows and crowded exhibitions. I feel like I can be myself in all of those environments, and I’m glad that I can be an enfant terrible in both cities.