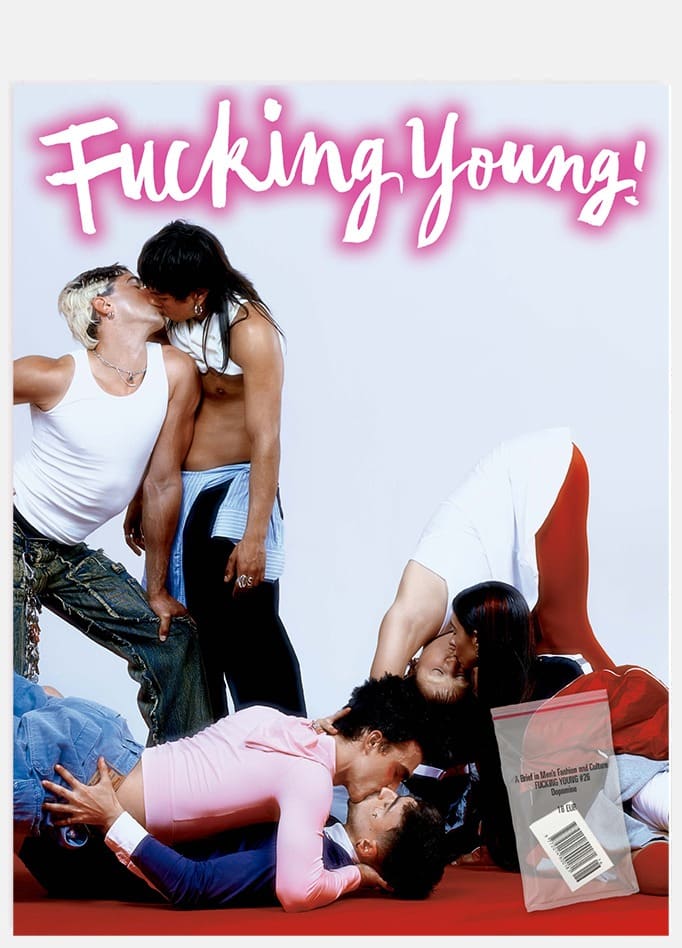

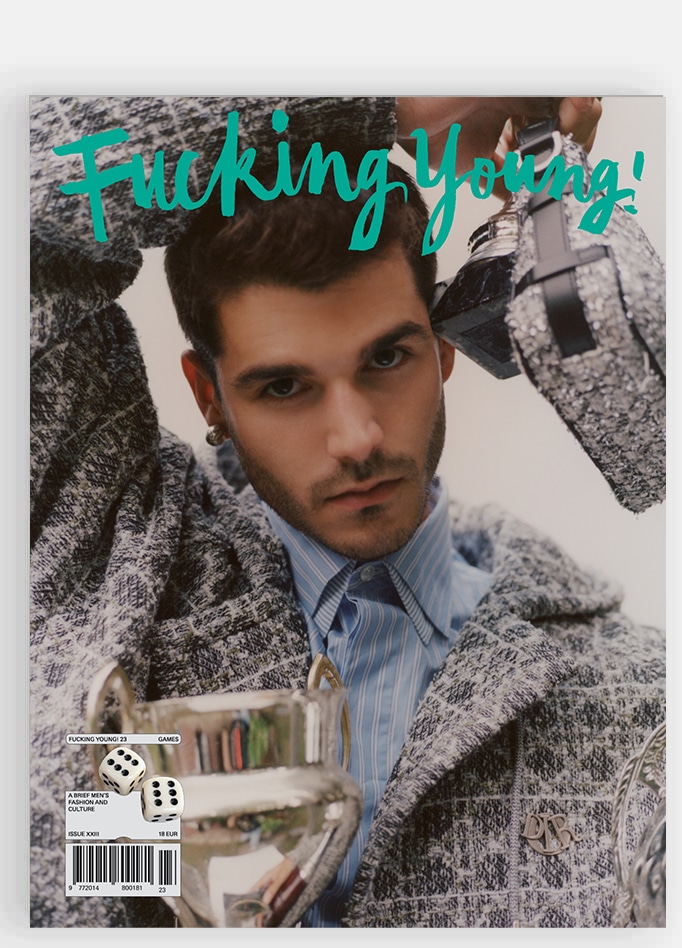

Jan Fabre by Willy Vanderperre

Featured among the collateral events of the 57th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, and open from 13 May to 26 November 2017, the exhibition Jan Fabre. Glass and Bone Sculptures 1977–2017 – curated by Giacinto Di Pietrantonio, Katerina Koskina and Dimitri Ozerkov, and promoted by GAMeC – Modern and Contemporary Art Gallery of Bergamo, in collaboration with EMST – National Museum of Contemporary Art of Athens and The State Hermitage Museum of Saint Petersburg – presents over forty sculptures by Jan Fabre (Antwerp, 1958) outlining the artist’s research since its origins, prompting a philosophical, spiritual and political reflection on life and death revolving around the crucial notion of metamorphosis. We sat down with Mr.Fabre to discuss this new exhibition that presents an unprecedented selection of works in glass and bone spanning forty years of the artist’s career, from 1977 to 2017.

Jan Fabre’s Skull with Squirrel 2017

Jan, why organising a glass and bone sculptural retrospective at this point of your career?

Back in 2011, when I presented PIETAS for the Biennale, I was working with the curator Giacinto di Pietrantonio and Berengo – the glass master from Murano who produced all my glass pieces from the last ten years. He came a couple of times to my studio in Antwerp and he saw my old glass works from the 70s and the 80s…

Sorry to interrupt, but who was making your glass pieces before Berengo?

I was doing it by myself with the help of a small company outside of Antwerp! So yeah, when he saw my pieces we decided to create a show comprising only my glass and bones artworks. Glass is an inherent part of Venice and it has such a strong tradition in Murano, so Giacinto found the location for me, this amazing monastery which is very quiet and close. He chosen it specifically because he knew my Monks sculpture series, so Abbey of San Gregorio was quite a natural choice and a way to bring together Belgian and Italian traditions!

So it felt like the right moment to bring together all your glass and bone sculptures?

Exactly, many of these pieces were never exhibited before! For example The Pacifier and Canoe have always been in private collections and never shown publicly until now… for that reason we thought it would be great to bring these two simultaneously strong and fragile materials together!

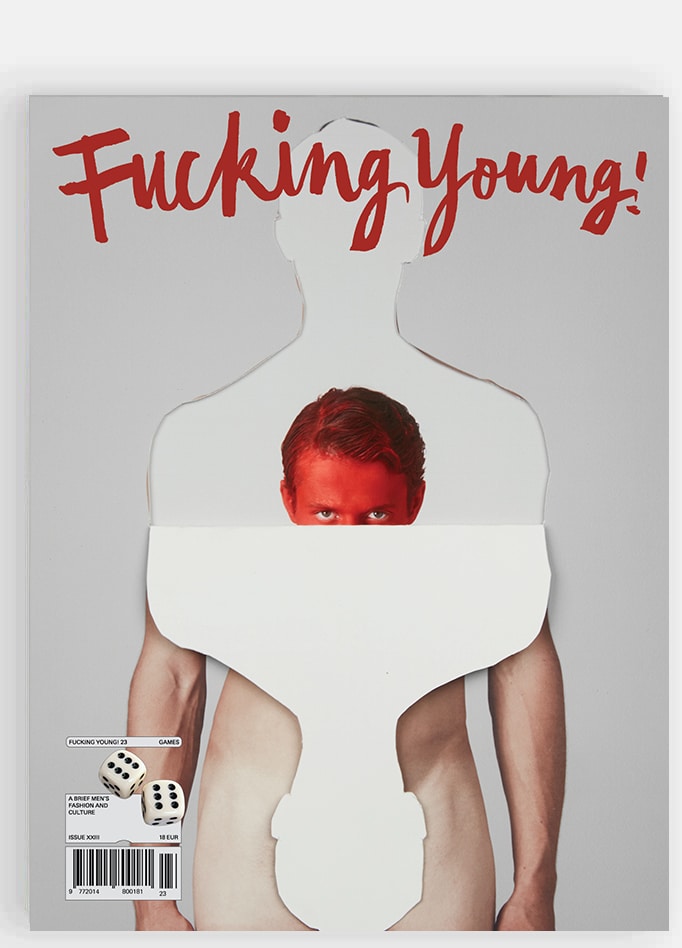

Jan Fabre’s Untitled 1988

You previously mentioned that your story with glass started back in your childhood… do you remember your first contact with that material? When I was a kid a remember digging out my first skeleton at my grandma’s backyard, I think it belong to a rat…

When I was young I remember experimenting a lot with my body, I remember cutting myself quite often, I remember the feeling of the glass in my skin and in my bones, I was about fourteen or fifteen years old. I was in my twenties when I made The Pacifier, at the time my teacher gave me a train ticket to Eindhoven so I could visit a Joseph Beuys exhibition. I was amazed by what I saw… when I came back home I made The Pacifier. That work represents what I think about art and beauty, it’s comforting and harmful at the same time…

Why it is so important for you to create a dialogue between your artworks and the exhibiting space?

It gives a better understanding of my work… I liked the Abbey of San Gregorio because it’s very modest, quiet and hidden but at the same time you’re in the centre of Venice. Damian Hirst’s show for example is the absolute opposite, it’s very British Empire, it’s about the glorification of power and money! Don’t get me wrong I like Damian, he’s a great artist, but you can observe the different traditions, the British are a powerful nation, they control the word. I am Belgian and we were occupied by the Spanish, the Dutch, the French and the Germans so our traditions are completely different, all of the great Flemish Masters were working under occupation and you can see it in the irony of their works. That’s the difference between being a Belgian artist and a British artist, my exhibition celebrates human vulnerability, Damian’s celebrates the power of economics and status…

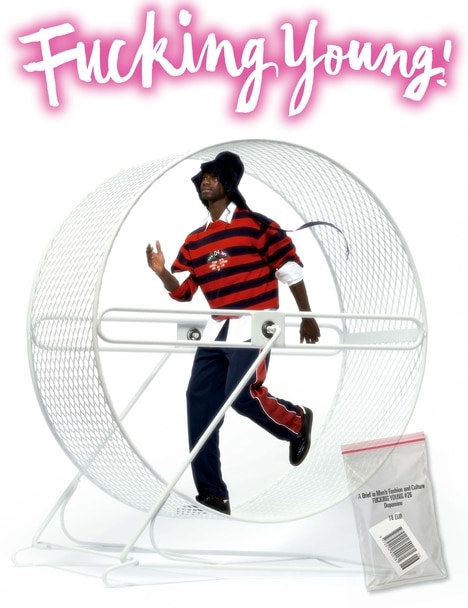

Jan Fabre’s The Future Merciful Phallus and Vagina 2011

What was your approach when planning your last show at the Hermitage in St.Petersburg?

To be honest with you, we were going back and forth with that exhibition for the last three years, but when it finally got confirmed I’ve chosen the Hermitage Flemish Masters rooms to set it up. As you know the Hermitage has many Flemish masterpieces, so I created special works of art for the occasion in dialogue with those paintings…

Jan Fabre’s Greek Gods in a Body-Landscape 2011

You were born, raised and currently based in Antwerp – a city with an impressive art, culture and fashion history – how strongly Antwerp influences your creative process?

I was born two hundred meters away from The Rubens House and my father took my to make drawings from Rubens paintings when I was seven years old, besides Rubens I’m still inspired by Van Dyck, Bosch, Jordaens and Van Eyck. When you look at the Flemish painting tradition, the vanitas, the skull is there since XIII century and it’s also very present in my body of work, it is something very important to me. I was twice in coma, so I’m kind of living a post-mortem state of life, for that reason the idea of death is very close to me!

How did you get in touch with the BIC pen ink, if I’m not wrong it was in the early 80s during your performative era?

It was cheap, I was a poor artist and you could find BIC pens everywhere, in cafés, you could literally steal them from everywhere, so I used the ink to draw in the beginning of my career. The blue is also an important colour in artistry, the Flemish Masters used lapis lazuli a lot, the BIC blue is a very peculiar, industrial blue, it’s a very beautiful chemical colour!

You grew up on the streets and had a quiet rough past, do you like to canalise your past into your art?

In its essence my art is very autobiographical, I’m a very local, provincial artist, everything you see in my art is located two hundred meters from my home.

Greek Gods in a Body-Landscape felt quite unusual in the middle of skulls and birds skeletons, do you feel inspired by palate and taste?

Of course, I’m Flemish, I’m Burgondic, I mean look at the Flemish paintings… when British, French and German art is essentially about the glorification of power, Flemish art it’s all about sex, drugs and rock’n’roll!

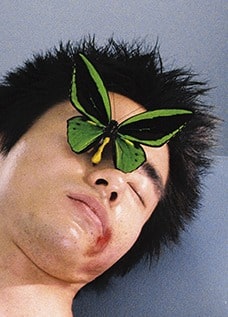

Jan Fabre’s The Pacifier 1977