Since I moved to London three years ago, there are two comments I often hear from people I have recently met: “You don’t look Mexican” and “you don’t look gay”.

The comment about my nationality has to do with people’s stereotypes of Mexico, a country they might not even have been to or know much about. It often bothers me, but usually, I just shrug, or mention my family’s mixed heritage, or just joke about leaving my sombrero at home. The comment on my sexuality, though, is definitely more damaging. Having one’s sexual orientation and identity exposed in casual conversation is something a heterosexual person will rarely have to go through. And yet, as queer people, we are expected to share intimate, deeply personal and sometimes even painful memories about who we are. As if we needed to explain ourselves for being homosexual. It is said that one is never fully out of the closet, and I believe that to be true. Every time I get told I don’t look gay it is like coming out again, and again, and again.

You don’t look gay. What exactly do they mean by that? Sometimes it sounds like a compliment, as in “Good for you!”, other times it might feel like an encouragement, “Keep up the good work, you almost look straight, mate”, often it comes as a sort of shock “Oh, and I thought you were just a normal person”. And then there is the inquiry, as in “are you sure you’re gay?”. It could be any of these or many more, one thing I know is I am exhausted from hearing it. It comes from straight people of many different backgrounds, regardless of their age, gender, nationality… they just somehow think it is a thought to be shared with me.

Every now and then, I get the other side of the spectrum, which is “Oh, I knew you were gay as soon as I saw you”.

How are gay men and women supposed to react when we get those sort of comments thrown our way? I really do not know. Mostly, I remain speechless. I think it is time we tell it like it is, these comments are micro-homophobic, no matter how well-intentioned the speaker thinks they are being. And just because we are used to hearing these comments by now, it does not mean we should allow them to keep on happening.

I have tried to search deep within my memory to remember exactly what it felt like when I first got told I did not look gay. I was raised in Querétaro, a quiet city in central Mexico, not too far away from the capital. Querétaro is also known as one of the most conservative and deeply Catholic areas in the country. Back in the day, when I was still in the process of coming out, if I ever heard “you don’t look gay”, it sort of felt like a compliment. In a way, that meant that I was safe. I did not make people uncomfortable with my “gayness”. I could blend in. I had conditioned myself through the years to a more contained version of myself, one that wouldn’t show that side of my personality as much. I am referring to traits which are commonly associated with being homosexual, but, I insist, are not exclusively representative of every gay man that has ever lived: a certain limpness of the hand, a pronunciation of specific words, a camp or theatrical way of expressing oneself, amongst other examples. I had fought throughout my life to hide these aspects of myself and I consciously molded myself to look like one of the others, the “normal ones”, the people I was raised with and whom I interacted with every day. But this never changed my sexual orientation.

By the time I was a teenager, I was deeply aware of my attraction to men. It became more frequent and evident and it would sometimes freak me out. I felt this towards actors in films, a couple of classmates, footballers on TV, to the point where I had to stop lying to myself. However, it is a process, and even if I knew it in my gut, it took some time for me to start sharing this information with others.

One day, looking through a family album, I stumbled upon a picture of myself at a Christmas dinner. There I was, around 8 years old, my hair covered with gel, my buttoned shirt, corduroy trousers. I was getting up from a couch with a smile, about to receive a present. The picture captured a certain gesture of my body language, a very effeminate pose that I find hard to describe even now. It is, however, still ingrained in my mind and I could probably draw it out of memory. I remember staring at that photograph as a frustrated, closeted adolescent. I was disgusted at myself. I looked…gay. The secret was out. It had been there all along, for all to see. I immediately removed the photo from the album, tore it to shreds and flushed it down the toilet. I then proceeded to search through my mother’s albums and get rid of every picture where I didn’t look “normal”. If there wasn’t enough evidence, then maybe it wasn’t true. That had not happened. I was not gay.

Years, later, I came out to my best friend. He had told me he was gay only a few months before, and to this day I consider him to be one of the bravest people I have ever met. He inspired me to finally start embracing myself for who I was and feeling proud of it. He gave me the strength I needed and then the process of telling friends and family was not as hard as I thought it was going to be. I was lucky. Most of the people I reached out to were incredibly supportive in the end, which was not something I expected at all. However, I distinctly remember coming out to a close “friend” who told me he was okay with me being gay, as long as he did not have to see me kissing another man. Ah, the fragile masculinity of the Mexican male.

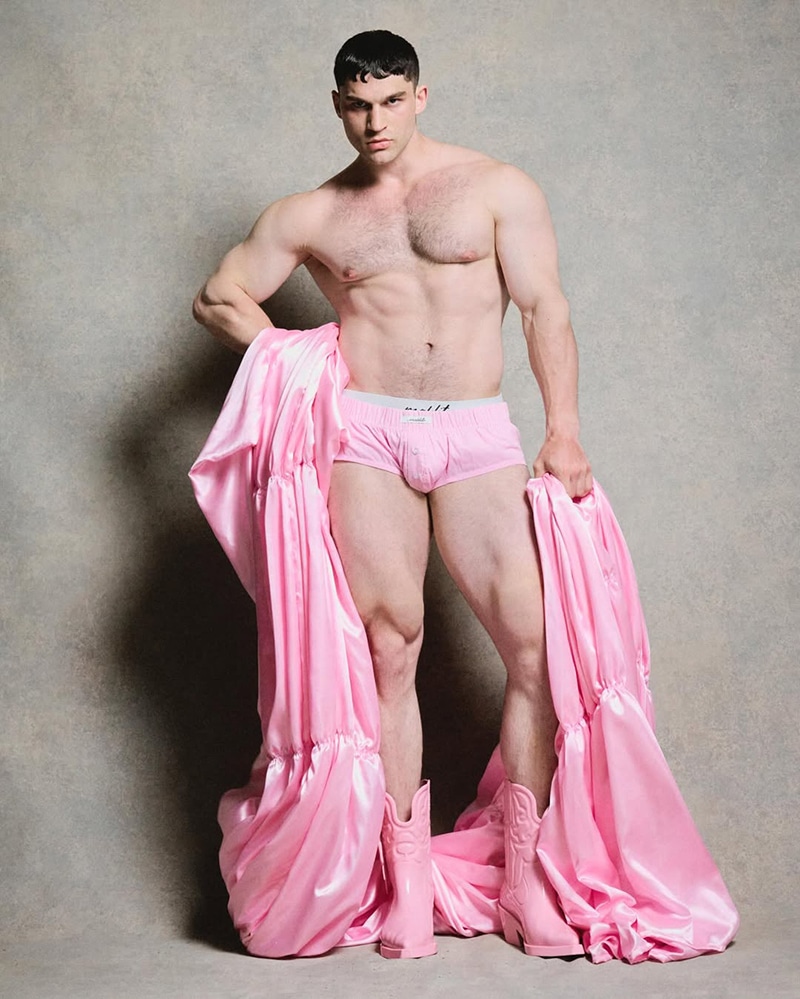

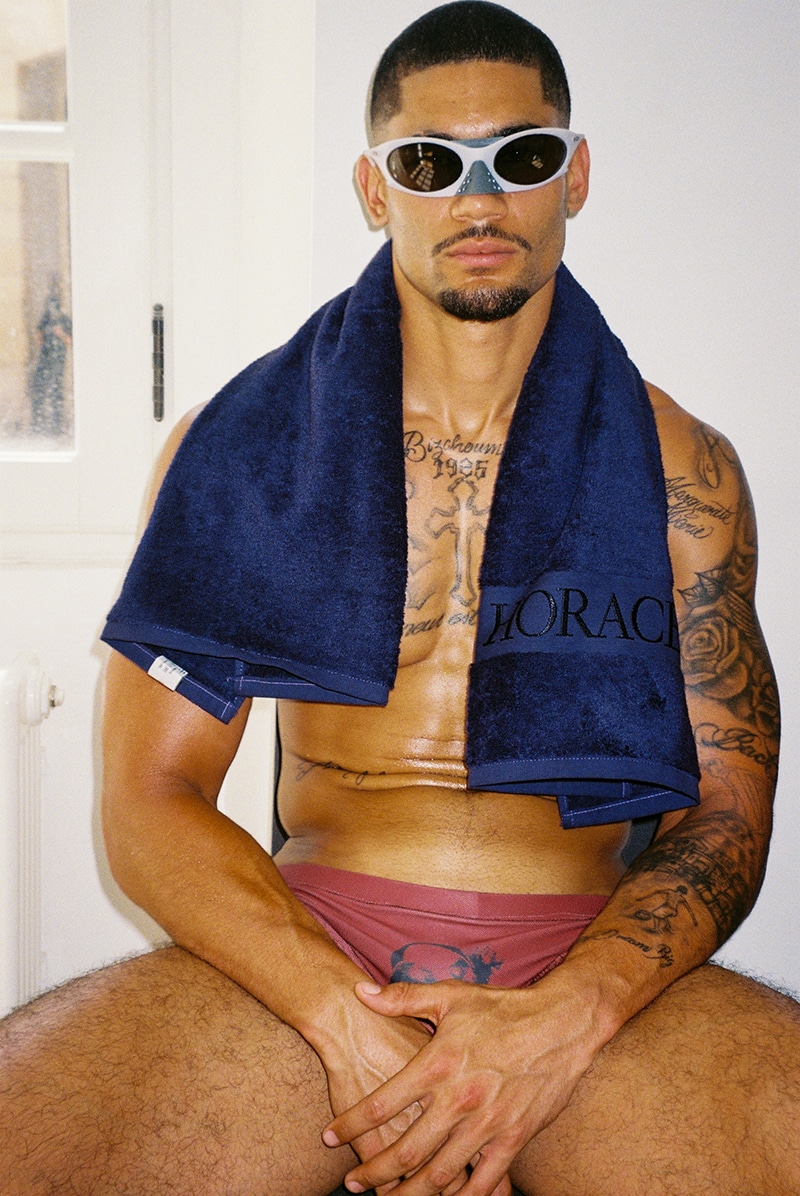

What does a gay person look like? There is not just one answer. If there is a human being that feels attracted to people of their same gender, or if those people identify as homosexual, then whatever they look like, that’s gay. Whether it be butch, effeminate, serious, camp, loud, introverted, fashionable, shabby, sporty, thin, short or tall. It will not necessarily show on the outside and it is time to talk openly about this and start burying the stereotypes.

I believe we as queer people have a choice to take action in everyday microaggressions and start making a difference. We get a chance to open up the conversation and get rid of prejudice. I have now decided I will not remain silent when I get told I don’t look gay. Nor will I do so when I get told I look very gay. Whatever the message that a person is trying to convey, I will kindly ask them to explain themselves. To elaborate on their statement. It is the perfect opportunity to engage in a dialogue and expose the comment for what it is, a manifestation of homophobia. If the person cannot find the words, I will be patient. The goal is to make them realize how much prejudice lies beneath their statement. If this means that person will never say that to another, then that small battle has been won.

I flushed that picture of myself down the toilet. That smiling boy with corduroy trousers was just being himself, unaware that he was being judged. The angry teenager that destroyed that photo wanted to kill that side of himself. He felt ashamed of the happy boy. I am as much one as I am the other, except now I am not afraid anymore. I am me and I am proud. I hope it shows on the outside, too.