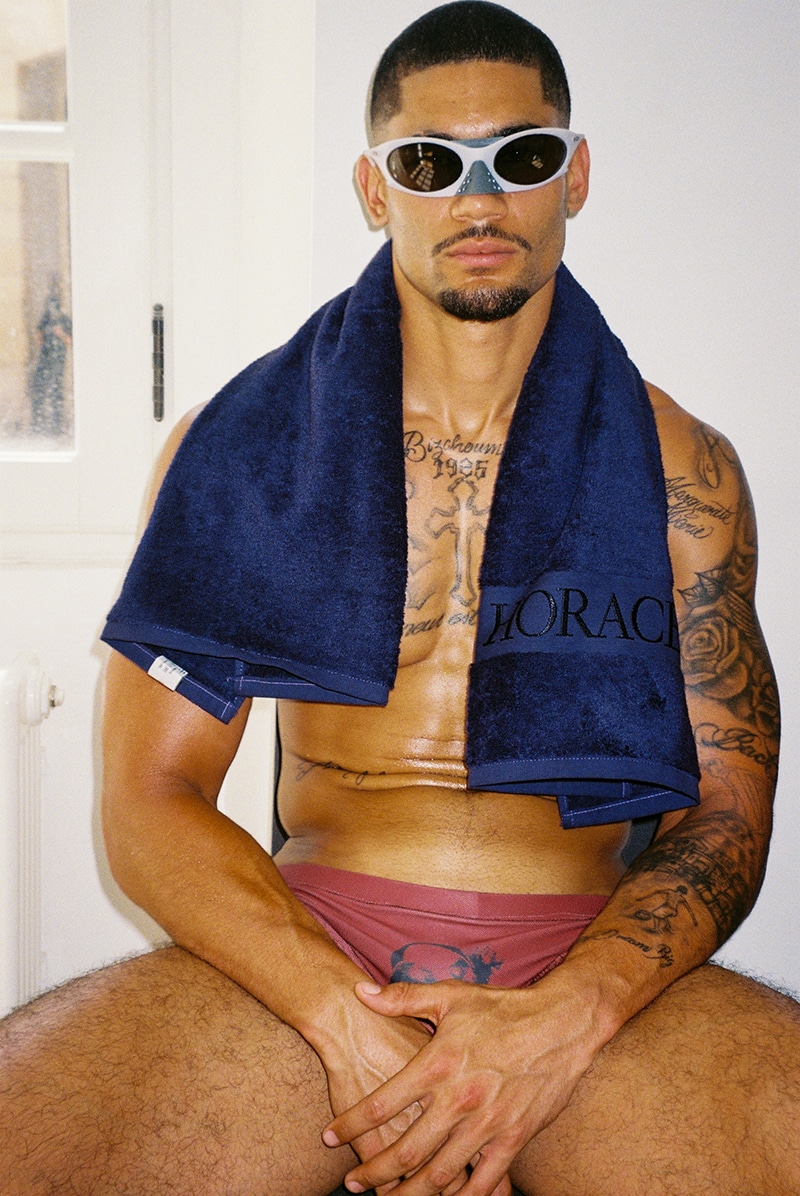

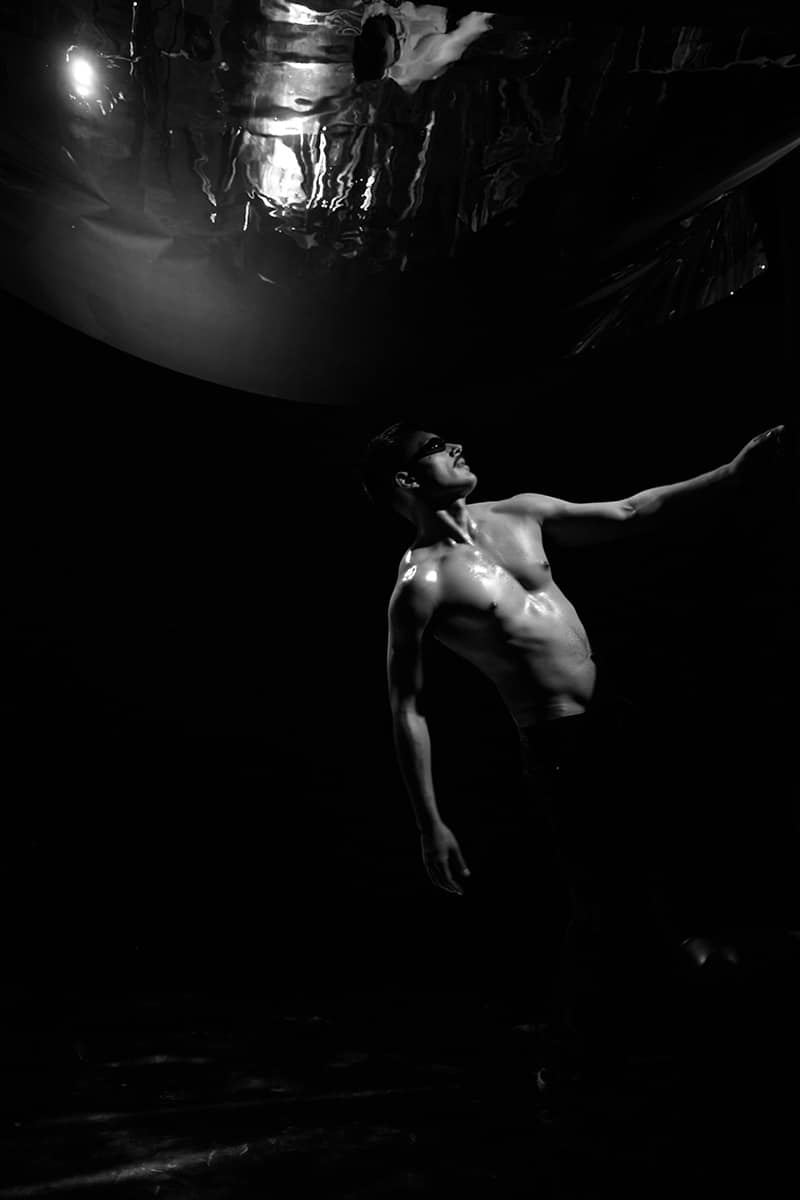

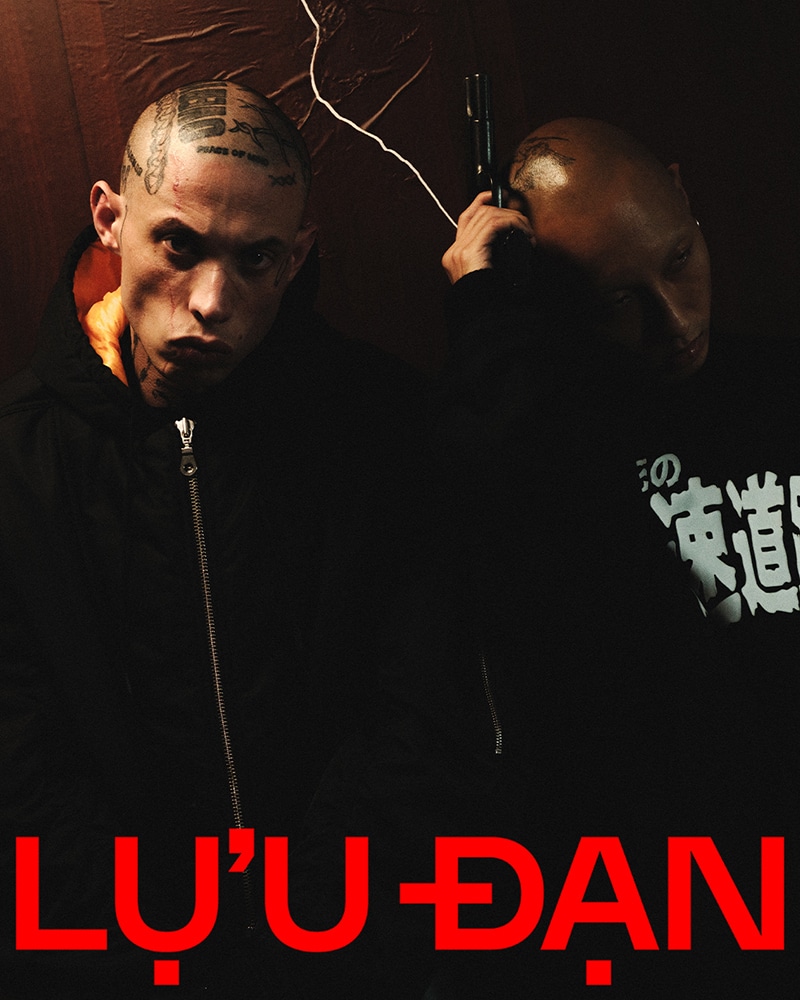

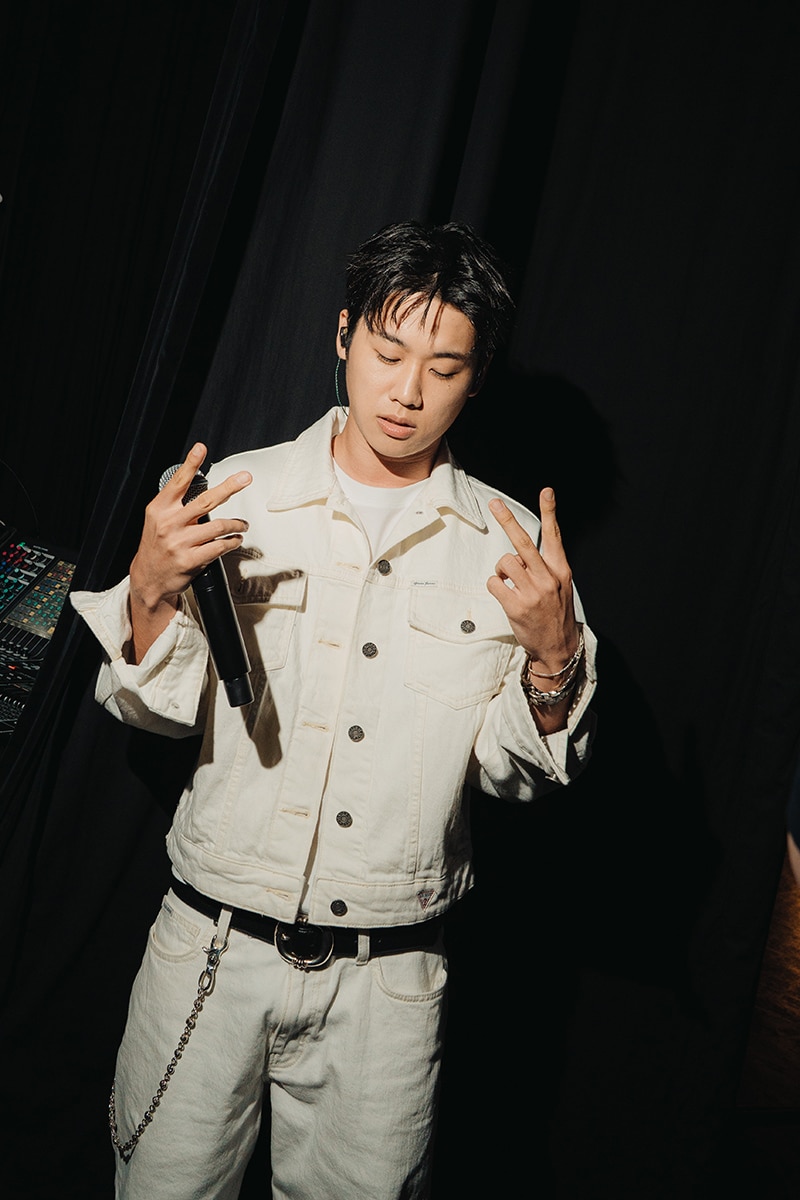

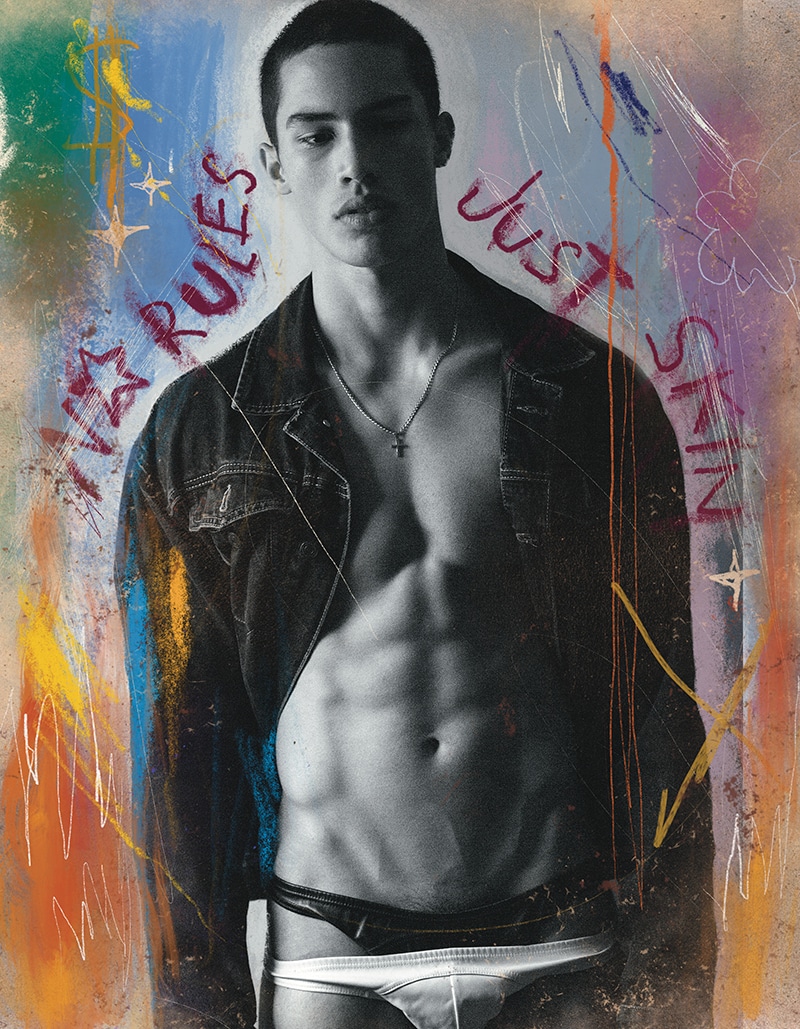

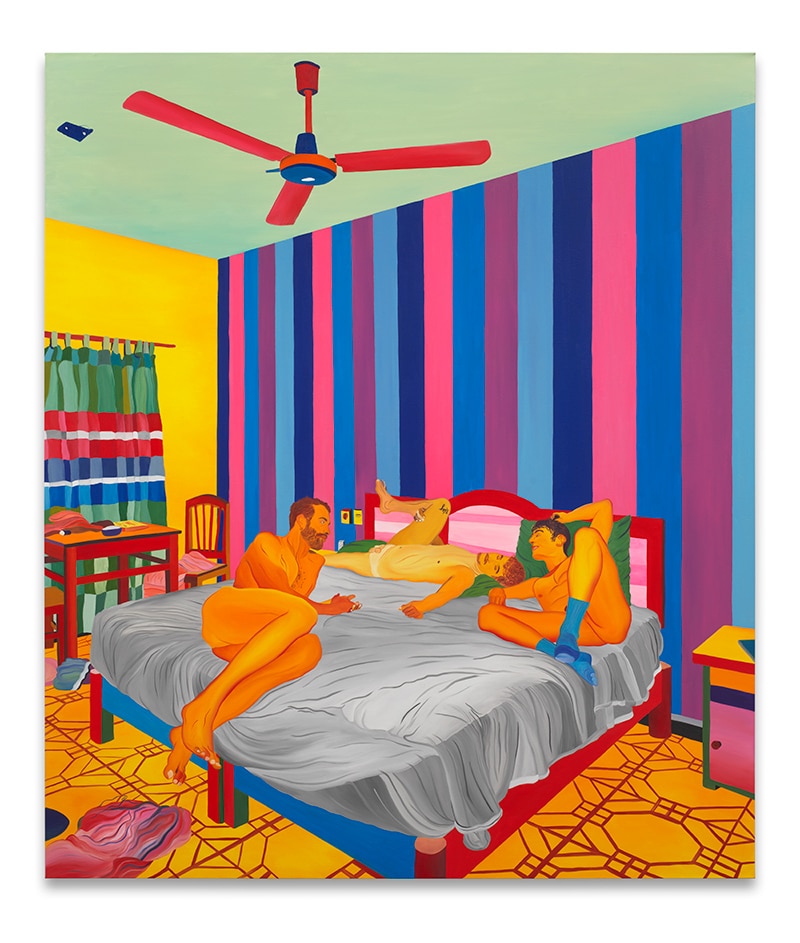

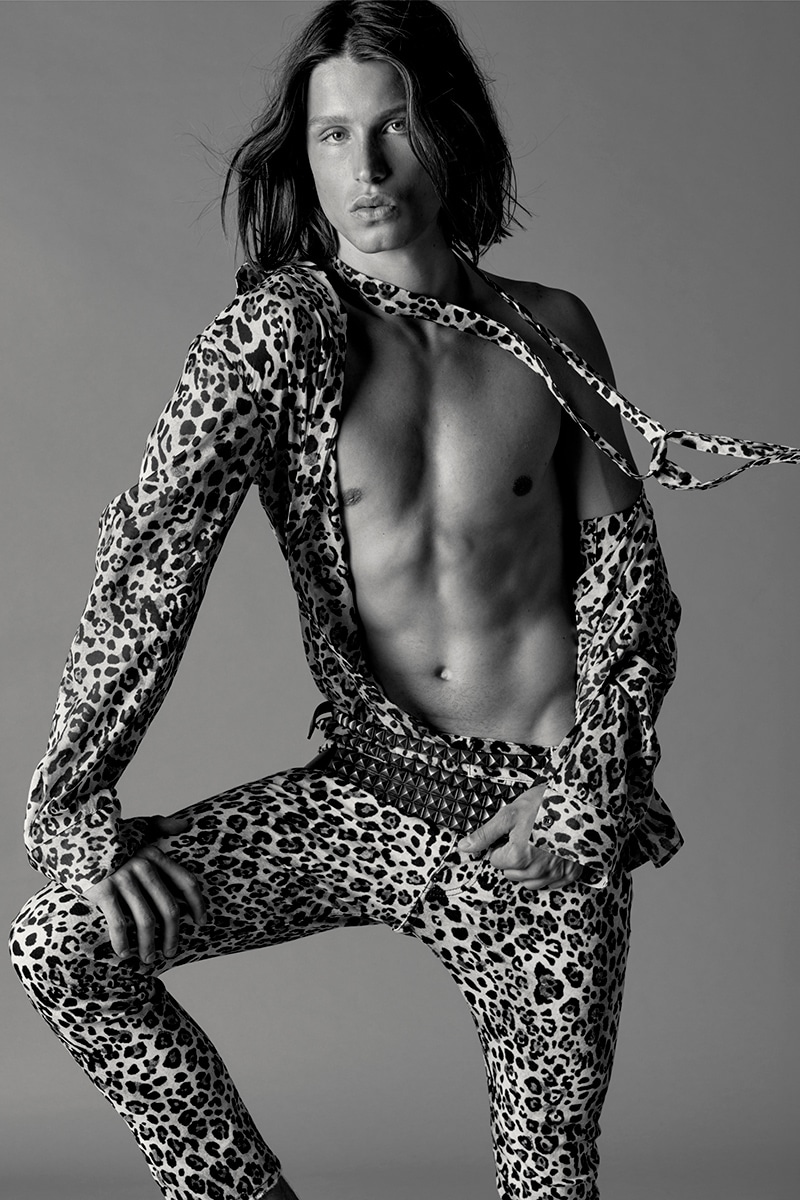

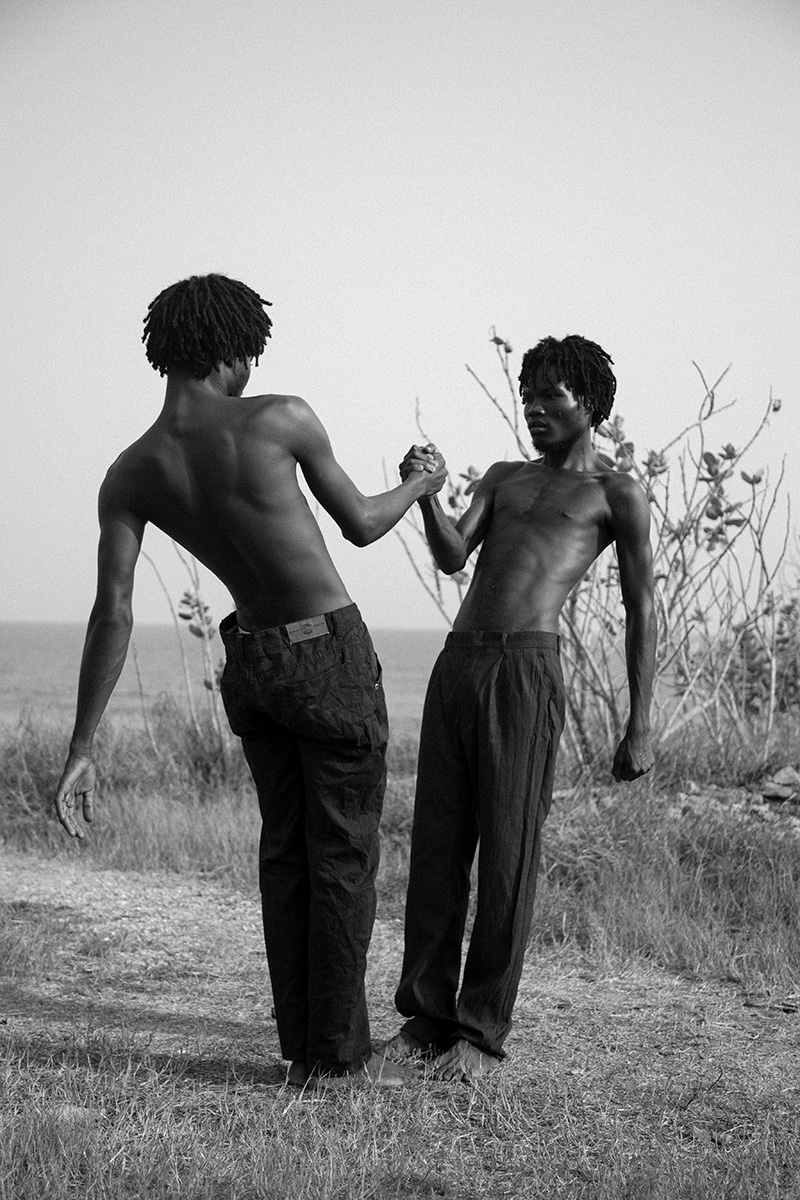

“I grew up in a highly conflicting family environment,” Ghanaian photographer David Nana Opoku Ansah tells me on a sunny afternoon in Accra. “I spent most of my childhood indoors reimagining a utopic society.” Leaving his mobile phone to one side and giving me full attention, David comes across as poised and cool despite the frenzied system he’s drowned in. “I’m reluctant to conventional narratives amidst culture,” he nimbly says, as a dynamic polymath whose shape-shifting vision documents everyday traditions in Ghana’s customs. A wonderful thing in an industry that seems to condone the whitewashing of nigh on every aspect of itself. The photographer is one with an agenda: he’s on a quest to alter representation in the mainstream masculinity from the commonly depicted aggressive and brutish type of images we’re often fed with, proving that races doesn’t equal to stereotypes. And that’s exciting. The artist tells me that in Ghana – like in many other parts of the world – the search for innovation and non-conformity is what prospers a creative practice. “You’ve got to be quick-witted and imaginative to thrive in these ends, that’s if you want to make photography your ultimate outlet of expression,” he reflects. With a great knack for innovation, his attempts could be described as poetic, gentle, and culturally rooted, bringing something fresh (and purposeful) to the humanity conundrum. We can only hope that audiences are woke enough to understand both the complexities and brilliance that come within these images, and don’t just see cute males. Here lies not some mild creative capitalising upon the novelty of the rural community and subsuming stolen aesthetics into elements of his practice, but a young culture fanatic who knows, and creates space for, parts of Accra’s society-driven scene. It’s conspicuous that his aesthetic is uncluttered and extensive, embracing the marginalised groups and issuing a narrative worth the checkout. Besides, Ansah urges to unfold a story that seeps from a vulnerable past. From castings, art direction, to chosen landscapes, the full picture feels like an integration of a legacy that longs its permanence. Dismantling an industry that is so known for its hierarchical nature is a truly tough thing, and all of the above reflections are exactly why Accra needs minds such as Ansah’s.

What first inspired you creatively?

Oh, man! I find it hard to answer this question every time because my inspiration changes from time to time. Occasionally, it could be mere intuition, but then it could boil down to films, friends, human emotions, and music. My childhood memories are a further cornerstone. I grew up in a highly conflicting “family against the world” environment, so I spent most of my childhood indoors reimagining a utopic society. That really inspires whatever I create.

You have an incredible ability to weave in Ghanaian history and heritage into your photographs. Fancy telling us more about it?

I’m constantly longing to capture blackness and community in new ways. Looking back at all the legends and great artists in previous decades, I realized we have become used to the traditional conventions of photography. My visual work breaks the rules of what people expect photographs to be. I push the limitations of the camera and capture where others do not think a significant moment is possible in Ghana. I look for color connections, textures, and the elements of both form and line, particularly when these elements interconnect with fleeting qualities of light. I’m anxious about the details that one observes in a photograph. I’m no longer just discovering photographic compositions; I create them and add my spin.

There’s a sort of power in the everyday culture that shines through your work. What particularly inspired it?

The minority side of youth culture in Accra is the prime point of inspiration. Moreover, the dynamism in Accra right now has freedom engraved all over its facet, from the likes of image-making, film, and music. The need to tell the stories myself drives it all. I’m searching for the visual essence of what we see around us, and I strongly feel the connection between image-making and other forms of art. I continue to explore the interactions between my camera, the world, and my identity when it comes to creating my images. Wandering the world with my camera, observing, is artistically inspiring.

I imagine it’s not an easy path to be a creative in Ghana. Could you tell us how you tackle your practice with the resources present in Africa?

Being a creative in Accra is hard – you’ll need all the mental support you can get. It’s more difficult when you are an artist who experiments and does a lot of contemporary work. There are a lot of trends and styles which make it easy to get lost. I take a lot of risks when it comes to my work. The just “do it, people are watching” mentality helps so much. I’m very specific about whom I work with, and I usually work with my friends who are into other art forms trying to reach the same end goal as me. Thoughtful collaborations, DIY culture, applying for intentional brands, and also pitching to publications out there helps with these. Also, you will need to think outside the box and be very innovative.

How do you power through the complexities?

Practice, researching, experimenting. Recently, I’ve been trying to take things easy and acted gentle on myself, accepting the fact that it’s okay to fail. Also, I try measuring my success. Once you are able to do that, you should be okay.

Taking into account the Ghanaian creative industry, what would you say is lacking the most?

Mentorship, funds, and grants: a working system to protect creatives and research facilities among society. These are things that will help a lot of emerging creatives in a long run. There are so many creatives killing it here. The only problem is most people don’t have access or know where to distribute their arts and how to find their target audience.