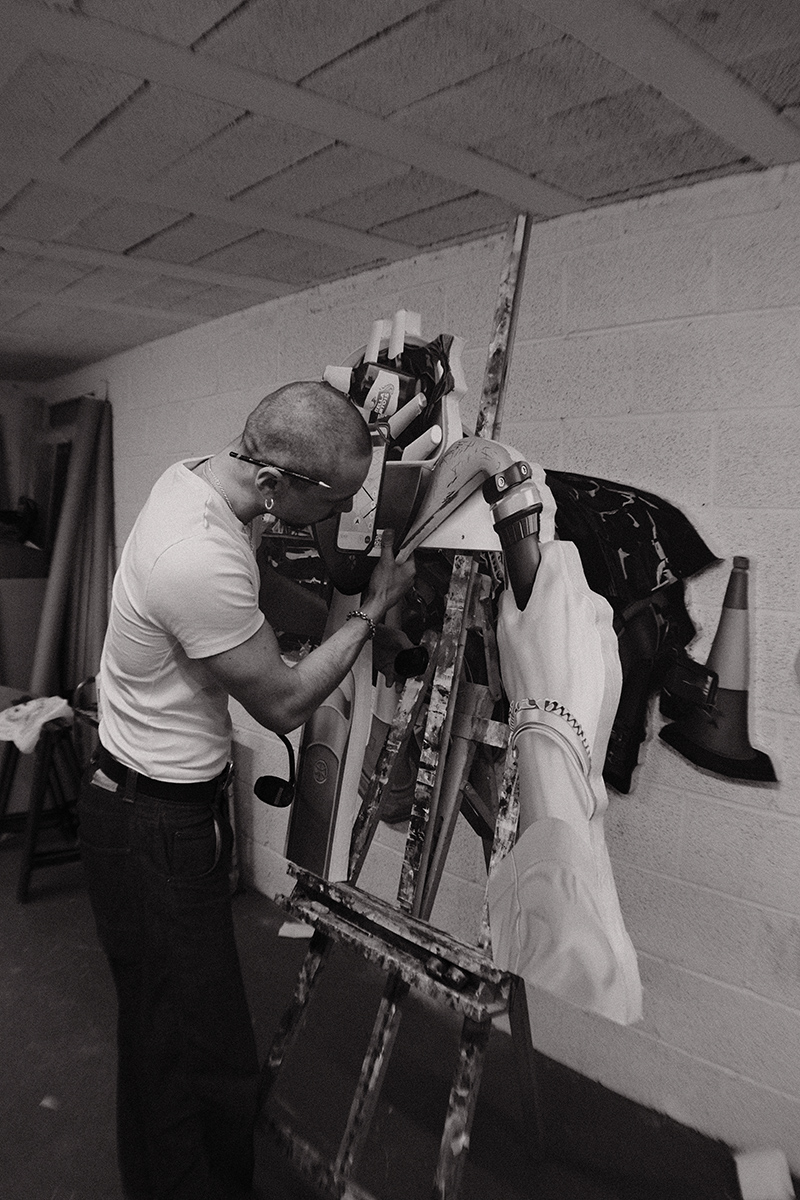

What a Shit Show opened yesterday in London, marking a significant milestone in the ascending career of Callum Eaton, the British artist trained at Goldsmiths, whose visual language has been shaped across Berlin, New York, among others. With sharp humour and an almost cinematic sensibility for capturing the discomforts of everyday life, Callum presents a perspective that oscillates between the intimate and the chaotic, the absurd and the instantly recognisable.

The exhibition features a new body of work in which the artist continues to investigate the tension that precedes disaster — those suspended micro-moments that have long defined his practice. His distinctive cut-out canvases, meticulous attention to detail, and ability to elevate domestic objects into visual relics signal a maturing vision. In these scenes — sometimes domestic, sometimes urban — humour interweaves with unease, producing a reading that is both accessible and richly complex.

Callum’s latest exhibition captures the turbulent spirit of 2025 with a disarming honesty, suggesting that beauty and humour can survive — and even flourish — amidst chaos. More than a summary of a challenging year, it affirms a style that seamlessly blends vulnerability, irony, and a sharply contemporary gaze. On the occasion of the opening, we spoke to Callum about tension, humour, improbable objects, and the peculiar pleasures of making art in unsettled times.

Hey Callum! Congrats on your new exhibition, What a Shit Show. Let’s start by talking about the moment when this title solidified as the right choice.

Thank you so much!

It’s actually a title I’ve wanted to use for a long time. The humour and the self-referential, mildly self-deprecating tone just hit the right nerve. It sat in my notes app for the better part of a year, and then one day, while on the phone with my sister, it suddenly felt possible, almost inevitable. Once the idea resurfaced, I couldn’t shake it off.

Definitely, it’s a good one. Was there ever an exhibition or cultural moment that ever left you thinking, What a shitty show, and lingered with you?

There wasn’t a single defining moment, but I do remember a trip to Berlin in 2019, just before graduating from Goldsmiths. My friend Charlie and I did all the galleries and museums, and I left feeling totally deflated, uninspired, and even questioning whether I wanted to be an artist anymore. Then my friend said one of the most important things I’ve ever been told: “Make what you want to see.” That sentence has shaped my practice ever since.

Your paintings often capture the suspended instant before disaster. How does that sense of anticipation relate to the chaos suggested by the title?

I’m fascinated by the quiet moment right before something goes wrong; the suspended breath, the slight unease. That tension sits perfectly alongside the chaotic humour of the title. The works aren’t about the disaster itself, but about the anticipation of it.

Recently, your focus has shifted from public spaces to more domestic micro-dramas. What led you toward these intimate environments?

I wanted to delve into the personal spaces we inhabit every day. When I started working with cut-out shaped canvases, it freed me up completely. I’d always loved the formal structure of those square, architectural paintings, but once I embraced the cut-outs, suddenly anything could become a painting. That shift naturally pulled me towards more intimate, domestic objects.

When selecting the objects that populate your scenes, what guides you—intuition, memory, or the demands of the painting itself?

Honestly, a bit of all three. For this upcoming show with Carl Kostyál, some objects, like the fire extinguisher, had been on my mind for a long time, and the cut-outs finally made them possible. But I also believe almost anything can become a subject. If you really take the time to look, you can find beauty and visual interest in even the most mundane things.

Several works include subtle traces of your presence—reflections, hands, glimpses of the artist. What role do these insertions play?

Before I focused on objects, I made a lot of self-portraits. Including these subtle reflections and fragments lets me gently reconnect with figuration without turning the whole painting into a portrait. It’s a way of acknowledging my presence without making the work about me. I believe some of my most successful works have a hint of me in them. In my previous show with Carl Kostyál in 2023, I had painted the Barbican laundrette machines. In one of them, there was a reflection of me taking the picture. Also, in my first series of ATM paintings, you could often see me reflected in the convex mirrors that hang on the sides of these machines. It locates the object in the real world but also places the viewer into the scene.

Humour appears throughout your work, often placed against tension. How do you see that balance functioning?

Right, humour is incredibly powerful.

Yes, it can be a deflection tactic, but I prefer using it to disarm. It gives people an accessible entry point, something to chuckle at before they start considering the deeper narratives or questions underneath. A bit of squirming is just a bonus.

Your method is deliberately slow in a hyper-fast visual culture. Has that pace become part of your statement?

At first, I didn’t think about it at all; painting slowly was just how I worked. But as my own TikTok and Reels addiction grew stronger, I started to really appreciate the slowness. The time embedded in a painting is one of the most beautiful things about it: each layer is made in a different mood, to different music, on a different day. I love Hockney’s quote: “Movies bring their time to you; you bring your time to painting.” No one dictates how long you look or where your eyes go. The viewer decides how much time to pour in.

In your practice, everyday objects are elevated into near-relics. What determines which fragments earn that attention?

That’s the million-dollar question. Some objects just feel right for the way I paint; others sneak up on me completely. Take Hurt People Hurt People, the car-crash painting. I stumbled across the crash cycling through the Hackney Marshes after getting lost—very easy to do if you’ve ever been there. I popped out on a totally different path, and suddenly there it was, this brutal wreck. It wasn’t something I was searching for, but it stopped me in my tracks. One thing I love about my practice is that a different route home can give me a whole new lifetime of subject matter. It’s all about being receptive.

Your residency in New York City brought a new velocity to the work—speed, tension, unpredictability. How did the city influence this body of paintings?

Any time you’re away from your usual environment, your senses sharpen. Cities like New York are full of what I call “urban debris,” these leftover traces of life that are both chaotic and strangely poetic. There’s also something calming about being in the eye of the storm. I’ve always imagined my ideal studio being a bit like Warhol’s Factory: constant buzz, constant people. My studio’s far too small for that, so I make do with a lot of phone calls and lots of music.

Critics often relate your work to hyper-realism and Pop traditions. Is this a lineage you carry consciously?

Of course. My earliest influences came from the Pop tradition. I loved the idea that something from everyday life could resonate so widely and hold its own within art history. I’ve also always been very inspired by the found-object work of artists like Duchamp. In a way, I see all my works as ready-mades—I just have to paint them to make them.

Looking back on 2025, with residencies and exhibitions across London, Paris, Berlin, and New York, how would you summarise the year?

Up and down. Personally, it’s been a very challenging year, but I think that builds character. Professionally, I’ve had opportunities I could only have dreamed of a few years ago. So overall, I’m incredibly grateful.

Presenting What a Shit Show, does it feel like a culmination of that year or more like a punctuation mark in the chaos?

It feels like a culmination. I think many people have felt this collective tension over the last twelve months. Almost everyone I talk to can’t wait for the year to be over, and honestly, I get it. So I’m hoping this show acts as a kind of full stop to a challenging year.

As you look toward 2026, where do you see the work heading—towards further domestic tension, sharpened humour, or new terrain?

I’ll keep making what I want to see. The humour isn’t going anywhere. The absurdity of everyday life is endless material. The challenge is just distilling it. I’m particularly excited to dive deeper into the NYC subway. It’s been immortalised in so many iconic films, and despite its grubbiness, it has a strange beauty that I can’t wait to explore further.

If a visitor were to walk out muttering, “What a shitty show,” how would you respond?

Thanks for coming.

LOL. Period!